That task accomplished, the Maori servant introduced herself. ‘My name is Maraea,’ she said. ‘My mistress is Mrs Rebecca Vickers. The Honourable Mr Vickers is currently in Europe on business. My mistress and I are only recently returned to Gisborne from England. Mr Vickers has been detained in London but is due to return soon. Be good enough to follow me, but stay far enough back so that people do not know that we are together.’

Paraiti was immediately offended, but it was too late — she had already agreed to the appointment. She followed Maraea away from the din of the crowded town into the private Pakeha part of Gisborne: not many people were about except for the occasional passing cars, their occupants too sophisticated to notice two Maori women walking along the suburban pavement.

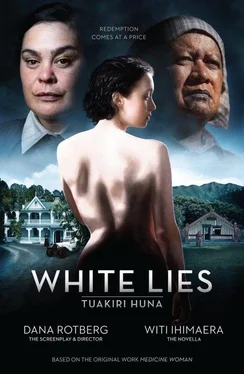

‘We are almost there,’ Maraea said as she led Paraiti around a corner and onto Waterside Drive. Here the elegant houses, most of them Edwardian, two-storeyed, faced the river where willow trees were greening along the banks. ‘The Vickers’ residence is the fourth house along, the big one with the rhododendron bushes and the wrought-iron gate. When we arrive at the house I will go in and see if it is safe for my mistress to see you. Kindly do not approach until I signal to you with my handkerchief.’

What have I got myself into? Paraiti wondered. Increasingly irritated, she watched Maraea walk towards the house, disappear and, after a minute or so, return to the street and wave her handkerchief. Paraiti approached and was just about to go through the gate when she heard Maraea whisper from the bushes: ‘Do not come in through the front entrance, fool. Go around to the side gate. I will open the back door for you.’

Paraiti obeyed and walked along the gravelled pathway. A Maori gardener at work in the garden tipped his hat to her. She recognised him as a Ringatu follower who lived on a nearby marae, and inclined her head. Maraea stood at the doorway to the kitchen.

‘Come in,’ she urged Paraiti. ‘Quickly now. And you,’ she said to the gardener, ‘Mrs Vickers is not pleased with the way you have trimmed the lawn. Do it again.’

Paraiti followed Maraea down a long corridor to the front of the house.

The sun shone through the stained-glass panels of the front door. The entrance hall was panelled with polished wood, and a Persian carpet covered the floor; the atmosphere was silent and heavy. A tall mahogany grandfather clock stood against one wall and a huge oval mirror hung on another. There was a small table with a visitors’ book, and a vase of chrysanthemums in the curve of the stairway. Hanging from the ceiling was a crystal chandelier.

‘Please take off your hat,’ Maraea instructed.

Paraiti looked up. Above the first landing was a large painting framed in gold of a lovely woman with red hair and blue eyes, dressed in an exquisite lace ball gown of an earlier generation; elegantly posed against a sylvan landscape, she was demure and sweet of smile. ‘Mrs Vickers’ mother,’ Maraea said, as she ushered Paraiti into the living room. ‘Lady Sarah Chichester. She was beautiful, was she not?’

‘Come away from the window.’

Paraiti had been waiting a good ten minutes before Mrs Vickers arrived. The room had all the trappings and accoutrements required by prosperous Pakeha gentry. The rich green velvet curtains were held back with gold tassels. Damask-covered antique chairs were arranged around small card tables; in front of one window was a charming chaise longue. The furnishings had an Oriental look — as if the Vickers had spent some time in the East — and indeed on the mantel above the fireplace was a photograph of a smiling couple, a young wife with her older husband, standing with an Indian potentate. Electric lights with decorative glass lampshades were set into the walls, and everywhere there were mirrors. Paraiti had gravitated to a window, wishing very much to open it and let some air in, and was looking out at the garden.

Turning, she immediately became disoriented; the hairs prickled on the back of her neck. In all the mirrors a young woman was reflected — she looked like the painting on the landing come to life. She was in her late twenties, with red, hennaed hair, tall and slim, and wearing a simple crêpe de Chine dress in soft shades of green. Which was the woman and which was her reflection? And how long had she been standing there?

On her guard, Paraiti watched as the woman approached her. As had been obvious when she drove past, she was pale, beautiful. Her skin was powdered to perfection; her eyes were green, flecked with gold, the irises large and mesmerising and full. Paraiti resisted the hypnotic gaze, and immediately the woman’s irises narrowed. Then she did something strange — almost seductive. She cupped Paraiti’s chin, lifted her face and clinically observed, then touched, the scar.

The act took Paraiti’s breath away. Nobody except Te Teira had ever been so intimate with her.

‘I was told you were ugly,’ the woman said in a clipped English accent, though not without sympathy. ‘But really, you are only burnt and scarred.’ She withdrew her hands, but the imprint of her fingers still scalded Paraiti’s skin. Then she turned, wandering through the room. ‘My name is Rebecca Vickers,’ she said. ‘Thank you for coming. And if you have stolen anything while you have been alone in the room, it would be wise of you to put it back where it belongs before you leave.’

Paraiti bit back a sharp retort. She tried to put a background to the woman: a well-bred English girl of good family, married to a man of wealth who travelled the world, accustomed to a household run by servants. She clearly regarded Paraiti as being on a similar social level to her maid. But there was also a sense of calculation, as if she was trying to manoeuvre Paraiti into a position of subservience, even of compliance.

‘What might I help you with, Mrs Vickers?’ Paraiti asked. She saw that Maraea had come into the room with a small bowl of water, a flannel and a large towel.

‘Thank you, Maraea.’ Casually, with great self-possession, Rebecca Vickers began to unbutton her dress; it fell to the floor. Her skin was whiter than white, and without blemish. Aware of her beauty, she stepped out of the garment, but kept on her high heels. Although she was wearing a silk slip, Paraiti immediately saw what her artfully designed clothes had been hiding: Mrs Vickers was pregnant. ‘It’s very simple,’ she said, as she removed her underwear ‘I’m carrying a child. I don’t want it. I want you to get rid of it.’

Her directness stunned Paraiti. She recognised the battle of wills that was going on. Mrs Vickers was obviously a woman used to getting her way, and there was nothing to stop Paraiti from leaving except that sense of fate; she would bide her time and play the game. ‘Would you lie on the sofa, please,’ she said brusquely.

‘Oh?’ Rebecca Vickers laughed. ‘I was expecting at least some questions and, surely, just a little … resistance.’

‘My time is precious,’ Paraiti answered as she began her examination, ‘and I doubt whether you are worth my trouble.’ She did not bother to warm her hands, and was pleased to see the younger woman flinch at their coldness. ‘When did you last menstruate? How many weeks have passed since then?’ she asked as she felt Mrs Vickers’ whare tangata — her house of birth — to ascertain the placement of the baby and the point the pregnancy had reached. The uterus had already grown to the height of the belly-button, and the skin was beginning to stretch.

Paraiti concluded her inspection. Mrs Vickers liked to be direct and was expecting … resistance … was she? Time then to be direct, to be resistant and push back. ‘You are a Pakeha,’ she began. ‘Why have you not gone to a doctor of your own kind?’

Читать дальше