On her father’s instruction, Paraiti therefore joined a band of Te Kooti’s followers who were travelling east. A year later Te Teira was finally released. He went straight to Te Kuiti. As soon as father and daughter saw each other, they clasped each other silently. It was there that Te Teira told Paraiti that her mother, Hera, had died in prison. ‘There’s only you and me now,’ he said.

‘What shall we do?’ Paraiti asked.

‘Go on living,’ he answered, ‘and do what we have always done: serve God and the people.’

He resumed his calling as a tohunga, preaching the gospel and working as a healer among the morehu, the followers of Te Kooti.

From that moment, they were never apart.

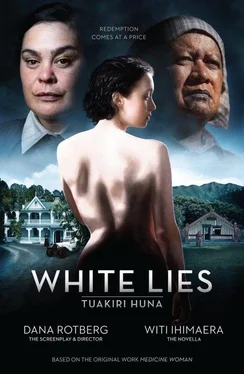

On this first day of June, in the Year of Our Lord, 1935, Paraiti is sixty-one years old and the land wars between Pakeha and Maori have been over for some forty years. Although she has not succeeded her father as a tohunga, Paraiti has continued his work as a traditional healer. Modern medical services may now be available in the many towns and cities that have sprung up around Aotearoa, but Maori in the backblocks and remote coastal areas still rely on their traditional medicine men and women. How can they afford the Pakeha doctors during these years of the Depression?

A few weeks ago, Paraiti was still in her village of Waituhi, in Poverty Bay, where she had settled during the second decade of the twentieth century. At the height of the terrible Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, when the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse reaped a rich harvest among Maori, Te Teira had received a plea for help from a powerful kuia of Waituhi. Her name was Riripeti and she was setting up a hospital to cater for the ill and dying, but she needed people with medical skills to staff it.

Paraiti was then forty-four, and Te Teira had implicit trust in her. ‘I have to stay here, daughter. You must go to Riripeti in my place.’ Obeying her father, Paraiti set off for Waituhi. As soon as she saw the valley, with its sacred mountain at one end and ancient fortress at the other — and the sparkling Waipaoa River running through it — she knew this would not be a temporary visit. Her sense of wonder mounted when she saw Riripeti’s canvas hospital, which people called Te Waka o Te Atua, The Ship of God, because when the tents were erected they looked like sails.

And then Paraiti saw the valley’s great meeting house, Rongopai, holding up the sky. Word of its fame had already circulated among the faithful, but even so, she was unprepared for its holiness. It was indeed a cathedral to the vision of the prophet, Te Kooti, so beautifully decorated and carved that she felt, on first entering it, that the angel who guarded it had sheathed his golden sword and let her into the Garden of Eden. The walls were like tall trees, elaborately painted in greens, blues and reds; she was wrapped in the glow of an illuminated forest. Through the branches flew fantastic birds, such species as were dreamed of in Paradise. And the Maori ancestors were everywhere, standing, running, climbing through this world before the Fall.

It was only a matter of time before she returned to stay.

The autumn was unseasonably cold in 1935 when Paraiti began preparing for her travels from Waituhi. The southerlies had driven into the foothills where she now lived in a two-room kauta close to the meeting house.

No matter the bitter weather, Paraiti was determined to keep to her seasonal trip as ordained by the Maori calendar — and the Maori New Year, Matariki, was imminent. Also, she had become stir-crazy and wanted to be out on the road.

After all, the people were waiting.

From her stockpile of medicines Paraiti carefully selected the small bottles and tins of ointments, philtres and lotions she thought she would need for the various village clinics, wrapping them separately for her saddlebags so that they wouldn’t clink or clang on the journey. Most of her medicines, however, she would gather fresh from the special secret places in the forest and along the coast, among them rimu gum for haemorrhaging, the mamaku pith for scrofulous tumours, seaweed for goitre and pirita for epilepsy.

For personal provisions she took only kao, dried kumara and water. Food would be her payment from her patients, and, should she require extra kai for herself and her animals, as always, the Lord and the land would provide: fern grounds, pa tuna, taro and kumara gardens and bird sanctuaries.

Paraiti took a small tent and a bedroll. For protection she put her rifle in a sling and a knife in her left boot. Although she might not be attractive, she was still a woman, and men were men.

She went to Rongopai to pray for safekeeping on her journey — surely there was no better place to set out from than this testament to the resilience of the people. Then she filled five blue bottles with the healing waters that bubbled from a deep underground spring behind the house, and sprinkled herself and her animals with the water.

Finally, Paraiti strapped the saddlebags around Kaihe’s girth, bridled and saddled Ataahua, got him to kneel as usual and climbed on. ‘I know, I know,’ she said to the horse as she straddled him, to stop his usual irritation. Straightaway, she urged him up: ‘Timata.’

She whistled to Tiaki to follow her. ‘Don’t fall too far behind,’ she called as she headed Ataahua into the foothills behind Waituhi.

As she passed by the houses of the village, people looked out and sighed, ‘Good, the old lady is on her way with her travelling garden. All’s right with the world.’ Every season without fail, the takuta was always about her work among the people; this season, the star cluster of Matariki was already gleaming in the night heaven.

A day’s ride took Paraiti to the boundary between the lands of Te Whanau a Kai and Tuhoe, and there she sought Rua’s Track, one of the great horse trails joining the central North Island to the tribes of Poverty Bay in the east. She followed the track up the Wharekopae River, through Waimaha by way of the Hangaroa Valley to Maungapohatu. Once upon a time there had been such a thriving community there, the holy citadel of Rua Kenana, another great prophet; survivors were still living within the mists of the mountain, waving at Paraiti as they scrabbled among their plantations, eking a living from the land.

Those who travelled Rua’s Track were mainly Maori like Paraiti herself; sometimes they were families, but most often they were foresters, labourers or pig hunters.

On her third day, she joined a wagon train of some forty people travelling in the same direction. ‘E hika,’ they jested. ‘Is the forest moving?’ Her saddlebags were overflowing with her herbal supplies. ‘Oh, it’s just you, Paraiti. E haere ana koe ki hea? Where are you going?’

Paraiti was a familiar sight and they were honoured to have her with them. She, in turn, valued the opportunity to sharpen up her social skills, to share a billy of manuka tea and flat bread, to spend time playing cards and to korero with some of the old ones about the way the world was changing. But the wagon train made slow progress, so Paraiti took her leave and journeyed on alone.

‘Ma te Atua koutou e manaaki,’ she called in farewell.

And now, Ruatahuna lay ahead.

Paraiti notices that Tiaki’s ears have pricked up. The dog looks at her: Are you deaf, mistress?

Then, even she hears the high tolling of a bell coming from Ruatahuna. ‘Ka tangi te pere,’ she nods. ‘I know, Tiaki, we will be late for the service.’

Читать дальше