And, of course, there is a sequence in the film in which a young boy has manuka honey trickled down his throat so that he can breathe.

I have tried to recreate Paraiti’s late nineteenth- and early to mid-twentieth-century world in the first half of the narrative, which follows her travels with horse, mule and dog throughout the wilderness tribal lands of my childhood. Most New Zealanders will know the historical context that I refer to, involving the prophet Te Kooti Arikirangi and his followers — the Ringatu. Surely the settler country feared Te Kooti. During the early days of the Land Wars between the two races, they had wrongly imprisoned him, in 1866, on the Chatham Islands, seven days’ sail from New Zealand. He was incarcerated for two long years, but during his time there the spirit of God visited him and inspired him to create a religion, the Ringatu, and to lead the Maori people out of bondage, just as Moses had done when he defied Pharaoh and led the Israelites out of Egypt. Te Kooti and his fledgling followers escaped from the Chathams by boat, and when they landed back in Aotearoa the Pakeha militia pursued them relentlessly. In retaliation, in November 1868, Te Kooti led an attack on the military garrison at Matawhero. It was an act of war and from then on the prophet and his followers were marked; a ransom was placed on Te Kooti’s head. For ten years he evaded capture, moving swiftly from one kainga to another, always supported by his followers.

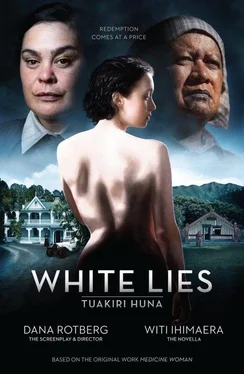

White Lies begins during these years. In it I have tried to document the world of the itinerant Maori healer, piecing it together from my own childhood experiences, local Ringatu and other informants and the scarce mentions in historic documents and other sources. My thanks to my dear mentor Maaka Jones — herself a Ringatu tohunga and versed in Maori medicine — and family and local Waituhi informants for oral stories about Paraiti and medicine women of her kind. My father, Te Haa o Ruhia, was the one who told me about traditional Maori massage and how his shoulder was set right simply by massaging the bones together; the account of Paraiti massaging her father with her loving hands at his death also comes from him. Thanks to the authors of the following books: Judith Binney’s Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki (Auckland University Press, 1995); Murdoch Riley and Brian Enting’s indispensable Maori Healing and Herbal Medicines (Viking Sevenseas, 1994); and Roger Neich’s Painted Histories: Early Maori Figurative Painting (Auckland University Press, 1993). Any errors of fact are mine. I am not an expert on the Ringatu or, particularly, on traditional healing and medicine, and I apologise for any inaccuracies. Thanks also to the Manukau Institute of Technology, the Arts Foundation of New Zealand and Creative New Zealand for research and funding assistance during the period I wrote the novella printed in this edition.

3. MERLE OBERON WAS A MAORI

However, when I was writing the novella I realised that the fictional Paraiti needed a moral dilemma, something that would challenge her purpose and her thinking: a confrontation with all that she values and believes.

In the second part of her story, therefore, I introduced a character named Rebecca Vickers, a young Pakeha society woman in her twenties, who asks Paraiti for an abortion. But Mrs Vickers and her maidservant, Maraea, in her fifties and a Maori, are not what they seem to be. In particular, Mrs Vickers has a lot at stake: if the baby is born, and if it is of dark complexion, people will realise that she is Maori.

This is where I have interpolated the story of actress Merle Oberon. It provides the heart of darkness for Medicine Woman and White Lies .

I have been fascinated by Merle Oberon ever since reading Merle: A Biography of Merle Oberon by Charles Higham and Roy Moseley (New English Library, 1983). All her life she lived a lie. She told the press that she had been born in Hobart, Tasmania. In 1965, she found herself in Sydney when she accompanied her then husband Bruno Pagliai, one of the richest men in Latin America, on an inaugural Aeronaves de Mexico flight to Australia. Invited to attend a banquet in her honour at Government House in Hobart, she first accepted, then fainted and cancelled; she was in Australia for only seventy-two hours.

Why the deception? Well, Merle Oberon had a lot to hide. She was, after all, one of the most beautiful women of her generation, a famous film actress with a fabulous almond-shaped face and slanting eyes set in a flawlesss white complexion. In a film career that lasted from 1930 to 1973, her electrifying beauty was highlighted in over fifty British, French, American and Mexican films, including playing Anne Boleyn to Charles Laughton in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), Cathy to Laurence Olivier’s Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights (1939), George Sand to Cornel Wilde’s Chopin in A Song to Remember (1945) and the Empress Josephine to Marlon Brando’s Napoleon in Desirée (1954). People thought she had discovered the fountain of youth because as she grew older she seemed to become more beautiful.

Merle Oberon achieved much more than a film career. In a life characterised by steely determination, sexual charisma and force of will, she moved in the international jet set, becoming one of the leading hostesses for her multi-millionaire husband, lavishly entertaining princes and presidents at their sumptuous home in Mexico. Higham and Moseley are of the view that she dominated not only Hollywood but the society of her generation.

All this, and yet she was the second daughter of a Eurasian girl, born on 19 February 1911 not in Tasmania, Australia, but in Bombay, India.

This was the description of Merle Oberon’s mother in Higham and Moseley’s book that took my attention: ‘Her name is Charlotte Constance Selby … She is a Christian girl, part Irish, part Singhalese, with Maori strains in her blood …’ The future actress was christened Estelle Merle. Her father was Arthur O’Brien Thompson, and the name Merle Oberon was fashioned out of her second Christian name and her father’s first surname.

When Merle Oberon became famous, her mother, father and her elder sister conspired to keep the truth of her Eurasian origins from the public. According to Higham and Moseley, cinematographers found ways of filming her so that her naturally dark skin and looks would be obscured. One such was the famed Gregg Toland, cameraman for Citizen Kane , who poured the whitest and most blazing arc lights directly into her face, making her look almost transparently fair and removing any hint of her Indian skin texture.

Merle Oberon’s mother, Charlotte, in fact lived with her daughter in Britain and the United States, and the biography relates this incident from the 1930s, told by actress Diana Napier (p. 28): ‘One afternoon I was having tea with Merle at her flat near Baker Street when for the first time I saw this little, plump Indian woman come into the room dressed in a sari. She stood nervous, hesitantly, as though waiting for orders. Merle was extremely embarrassed. She spoke to her mother in Hindustani. The lady hardly said anything at all. She was very, very quiet.’

Charlotte Constance Selby died with her daughter at her bedside on 28 April 1937. Very few people knew that the Indian woman, called by Merle Oberon her ayah or nanny, had been her mother. Neither woman had ever shown any sign of family affection. To have done so would have destroyed Merle Oberon’s ‘English rose’ reputation at a time when women of colour faced harrowing prejudice and racism. In the British film industry, such a woman would never have made it to the front rank of actors — and would not have survived the furore if the truth had become known.

Читать дальше