He nodded, seeming to weigh the thought, while inside him he fought to keep from laughing. Crying. Working too hard? He wasn’t working at all. If he was under a strain, it certainly had nothing to do with work.

“Maybe you’re right,” he said. “I guess I’ve been pushing lately. I’ll have to try taking things a little easier.”

She nodded, moved closer to him, slid an arm around his waist and laid her head against his chest. Reflexively he put a protective arm around her. His wife, he thought, hearing the words in his mind. His wife, the mother of his children. “Elaine the fair, Elaine the beautiful, Elaine the Lily Maid of Astolat...”

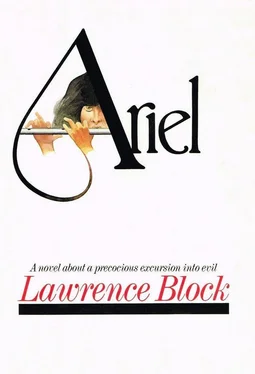

He hugged his wife close, closed his eyes, and saw Bobbie’s face grinning mockingly at him, one eye squinched shut in a lewd wink, the inevitable cigarette drooping from the corner of her mouth — the face flashed and was gone, and then it was Ariel’s face, burning with an unholy knowledge... then melting into the face in the portrait, the face of Grace Molineaux...

He opened his eyes, and he was standing in his own house with his arm around his wife, inhaling the fragrance of her hair.

Easy, boy, he told himself sardonically. You’ve been working too hard. You must be under a strain.

That night Ariel went to her room directly after dinner. She tried to play the flute but the music didn’t want to come and she gave up on it. She did her homework, then sprawled on her bed with a book and tried to get lost in it. But her mind kept wandering away from the words on the page and after a while she closed the book and set it aside.

She looked up at the portrait.

“Old enough to be your father.”

She hadn’t reacted openly to Erskine’s words, even though the impact was like getting hit between the eyes with a fist.

Jeffrey Channing was old enough to be her father. And he’d come over to the house to talk to Roberta, and had turned up at Caleb’s funeral, and had then taken to lurking in his car, spying on her and... Suppose he was her father? Suppose thirteen years ago Jeffrey Channing had an affair with someone, maybe with a girl much younger than he was, for example. She got pregnant, but he was married and couldn’t marry her. The girl had the baby, and she put it up for adoption, or maybe she died in childbirth, but anyway , the baby wound up getting adopted by David and Roberta Jardell... And then years later Jeffrey Channing found out about it, he was a lawyer and he would know how to investigate that sort of thing... In between he’d had two children of his own, Greta and Debbie. And they didn’t know about Ariel, and neither did Mrs. Channing. What was her name, again? Erskine had found it out and she ought to be able to remember it, but it wouldn’t come to mind. Well, it didn’t matter. Anyway, they didn’t know about Ariel. (Elaine, that was Mrs. Channing’s name.) They didn’t know, and her fa — Jeffrey Channing wanted to take an interest in his... in her and learn a little about her without anybody finding out his secret. Maybe Roberta herself didn’t know who he really was. If he was a lawyer, he probably had some clever way or other to explain what he was doing.

Father.

She tested the word, let it echo in her mind. Part of her wanted to believe that this handsome well-dressed man was indeed her father. Another part couldn’t regard the notion as anything more than a seductive fantasy. At least it made for a harmless mind-game... Ariel Channing...

Twice now they had exchanged long glances, their eyes sort of locked in a wordless stare. Both times he had been behind the wheel of his Buick while she had been walking with Erskine. Both times something had passed between them, something special... was the look they exchanged a father’s and daughter’s?

It was exciting and upsetting and a little crazy. After a while she ran a tub, took a bath, making the water hotter than usual and adding some of Roberta’s bath salts. She lay back with her eyes closed, soaking for a long time in the hot tub. Then, drained, she dried off and went to bed.

She lay in bed exhausted but unable to sleep. She began touching herself, as if to reassure herself that she was there, as if to read her features as a blind person might. She touched her face, her shoulders, her breasts. She touched between her legs, then put her hand to her face and breathed in her own scent.

Images bombarded her. At one point she saw Channing standing alongside the woman in the portrait. They were dressed like the man and woman in American Gothic. Instead of a rose, the woman was holding a baby. For a moment the baby was herself, and then it was Caleb, and then it was a rose again, a rose that wilted until a drop of blood fell from its petals.

Ariel slept.

Jeff couldn’t sleep. After an hour’s tossing and turning he gave up and got out of bed. In the living room he tried to concentrate on a magazine but couldn’t make sense of what he was reading. He tossed it aside and tried to make sense out of the afternoon.

Had he really seen them?

It was hard to believe he had seen two children who looked like them. Their appearance was too distinctive and he had had too good a look at them to have been confused in that fashion. Of course it was possible that he had fancied a resemblance where none existed. He’d been tired, emotionally exhausted, and he could have seen two children who really looked nothing like Ariel and her friend and his imagination could have connected the dots.

Or there might have been no one there at all. No boy and girl walking past his house. People under a strain sometimes saw things that weren’t there. It was not comforting to admit that possibility where one’s own self was concerned, but it was not a possibility which could be categorically denied.

Finally, it was possible that he had seen precisely what he had thought he had seen. But what on God’s earth had sent them wandering through his neighborhood? It was miles from where they lived. Assuming they had a reason to be in Charleston Heights, was it sheer coincidence that put them in front of his house on his return?

Or had they come looking for him?

He put his head in his hands, pressing against his temples, trying to make his thoughts run along logical lines. There ought to be some way to make sense of all this and he couldn’t seem to latch onto it. Was all of this linked to pressure resulting from his affair with Bobbie? Or did it somehow tie in with what he had learned about the portrait?

He closed his eyes, and his mind filled with Grace Molineaux’s image. It flickered and was gone, replaced, for God’s sake, by a vision of Ariel. He wanted to open his eyes, but half afraid that should he do so he’d discover her standing there in front of him.

He opened his eyes. He was alone in the room, and he reacted to this discovery with a mixture of relief and disappointment.

It was impossible to say what woke her. Roberta was sleeping soundly, deep in Valium-induced dreamlessness, when some force propelled her up out of sleep. She was suddenly sitting up in bed with her eyes open.

In the other bed, deep in his usual brandy stupor, David grunted and rolled over onto his side. Across the room, beside the window, stood the woman in the shawl.

She was as formless, as imperfectly defined, as on the first night Roberta had seen her three nights before Caleb’s death. Her pale face loomed in the dimness, and all the rest of her was shadowy and indistinct, shifting as if tossed by air currents in the room.

Was it a dream? She had dreamed this woman’s appearance once. Was she dreaming now?

“What do you want?”

Had she spoken the words out loud or merely voiced them in her mind? The apparition did not react, nor did David stir. He slept on, unaware.

Читать дальше