Perhaps for lack of evidence, perhaps in deference to her family background and her husband’s war record, no charges were brought against Grace Molineaux. Her name disappeared abruptly from the newspapers, only to reappear just as abruptly on November 4th, when the newspaper reported her sudden death as a result of gas inhalation.

She had been found, it was reported, in the kitchen of her Legare Street home. While suicide was not mentioned, in keeping with the newspaper’s evident view of decorous journalism, the inference was inescapable.

She killed her kids, Jeff thought. Maybe the first one did die of crib death or some nineteenth-century infant malady. That was certainly possible, but somewhere along the line Grace had snapped, and she’d certainly murdered the other three children, and when she found she couldn’t live with herself she put her head in the oven and turned on the gas.

Could it be the same stove? The one Roberta cooked on, the one with the eccentric pilot lights? Was her restless ghost haunting the stove, leaving it only to appear in the upstairs bedroom with a baby in her arms? Lord, was this Jeff Channing, man of laws, thinking this way...?

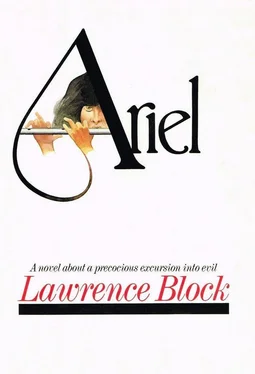

His head was reeling by the time he left the newspaper offices. His nostrils were full of the musty smell of ancient newsprint. He’d been unable to find a photograph of Grace Molineaux, but he had no doubt that she was the woman whose portrait hung in Ariel’s room. He had no grounds for this belief. There was no evidence that Grace had ever had her portrait painted, or that her appearance had been anything like that of the woman in question. But he only had to remember the expression on that face, the look in those eyes, to be sure the likeness was that of Grace Molineaux, madwoman, murderess, and suicide. Good Lord...

He did not return to his office, did not even consider returning to his office, but walked instead to where he’d left his car, got into it and drove around. He passed the house on Legare Street three or four times, returning to it compulsively, staring at its brick-clad bulk as if it might reveal itself to him. Roberta’s car was parked at the curb, but he had no desire to stop for a word with her. He couldn’t tell her what he had learned. She was under a strain as it was, having a tough time emotionally and—

Just like Grace Molineaux, he thought.

And pushed the thought aside, and drove aimlessly around, trying to think if there was any further direction his investigations might take. Could he possibly establish whether the painting was of Grace? It occurred to him that there might be a way. Even if the painting was unsigned, a comparison of the style with that of various local portraitists of the time might establish who had painted it. Painters frequently kept records, and historical societies tended to preserve records of that sort. A little creative research might clear things up.

For that matter, a little further research in the newspaper files might be time well spent. He already knew as much as he wanted to know about Grace Molineaux, but it occurred to him to wonder what effect her house might have had on persons who had occupied it after her death. He already knew the house had changed hands at an unseemly rate. Had there been a disproportionate number of deaths? Was unexplained infant mortality a legacy of Grace’s?

Or had other people sensed something and moved away, before their lives were affected by whatever permeated the damp old walls? Maybe the house had been waiting all these years, waiting for the Jardells... A house waiting? The defense better rest...

He drove around until he tired of aimless driving, then found a main avenue and headed north. It was getting on toward dinner time. Time to leave both the nineteenth century and the cloying streets of Old Charleston. Time to get back to his own time, his own house, his own wife and children.

Until, on his own block just two doors from his own house, he saw them.

Erskine and Ariel.

The bus heading back into the city was two-thirds empty. Ariel and Erskine sat all the way in the back. Erskine had his legs draped over the back of the seat in front of them.

“I almost ran,” he said.

“Why run?”

“No reason. Just blind panic. When he drove up and saw us I thought we were going to be in trouble.”

“We didn’t do anything.”

“I know. I’m not saying it makes any sense. I just figured he’d be pissed off. We looked at his house and talked to his kids.”

“Just one of his kids.”

“Just Debbie. Greta had to practice the piano. She’s only nine. Isn’t that young for piano lessons?”

“Some kids start taking when they’re seven. I wonder if she’s any good.”

“You could play duets, Jardell. Ladies and gentlemen, for your listening pleasure, the piano artistry of Miss Greta Channing and the flute wizardry of Miss Ariel Jardell. For their first selection, your ears will be treated to... to what?”

“ Go Tell Aunt Rhody, I suppose. We used to live in a house like that one. Erskine, what if we’re moving back?”

“To the same house?”

“To one like it. To any other house. I really don’t want to move.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“Right.”

They were silent for a moment. Erskine burped and Ariel clucked her tongue reprovingly. He took his feet down from the seat in front of him and yawned elaborately.

Then he said, “You were very cool. Just staring back at him when he stopped the car.”

“Well, it never occurred to me to run. I was surprised to see him, but after all it’s his house. I guess he has a right to go there.”

“Weren’t you scared?”

“No.”

“Not even when he stopped the car alongside us?”

“No.”

He glanced at her. “I get the feeling you sort of like him,” he said. “He can be your new boyfriend.”

“Well, he’s not bad-looking.”

“Huh?”

“He’s not. I think he’s handsome.”

“Oh, come on, Jardell. He’s like you said in the beginning, he looks like a television emcee. Remember the Funeral Game? ”

“That doesn’t keep him from being good-looking. It bugs you, doesn’t it?”

“What bugs me?”

“That I think he’s handsome. It really bugs you.”

“You can think Dracula’s handsome if you want. I don’t give a fuck.”

“Really bugs you.”

“Just cut it out, Jardell. That lah-di-dah singsong teasing shit.”

“Hey, calm down.”

“You want to think he’s handsome, that’s fine with me. The big dumb shit’s old enough to be your father.”

“Two children,” Jeff explained. “A boy and a girl. About, oh, twelve or thirteen years old. The girl’s the taller of the two. A very long, pale face. The boy’s very small with thick eyeglasses.”

“What about them, darling?”

“I saw them out front,” he said. “Just as I was driving up. I hadn’t seen them before.”

“You know this neighborhood. The only constant is change. People move in and out all the time, and the number of children—”

“I thought they might have come here. To the house, I mean.”

“What made you think that?”

“I don’t know. The way they were walking. There was something sort of furtive about them, as if they’d just broken a window of ours or something like that.”

“You got this impression just watching them pass by?”

He shook his head, dismissing the thought. “If you didn’t notice them, there’s nothing to talk about,” he said. “Maybe Debbie or Greta saw them.”

“Jeff...”

“What?”

“Are you feeling all right, darling?”

“Of course. Why?”

“You seem under a strain. I wonder if you haven’t been working too hard.”

Читать дальше