‘Have you seen these children?’ asked Ellie, gesturing at the other beds and to a mother slowly leading her bald daughter and drip stand along the ward. ‘Think about it.’

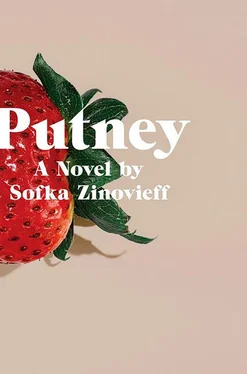

Ellie went home to rest; she hadn’t slept all night. Ed was due back from a trip and she needed to tell him what had happened. Almost as soon as Ellie left, Ralph appeared with a bounce in his step and a bumptious smile on his face. He was clutching a potted strawberry plant covered in pretty flowers and a bottle of Lucozade. Jane cringed with irritation. He was like an actor wanting to make an impact – scheming for maximum effect, calculating his charm. She noted how quickly several smiling nurses came to help – a plate for the plant, a plastic beaker for the drink. He is so fake, she thought, and the nurses’ reactions so obvious.

‘Naughty girls. Very naughty.’ Ralph chuckled indulgently. ‘What a fright you’ve given your parents. Crikey, a hangover is one thing, but hospitals… not a good idea.’ Bending over, he kissed Daphne very gently on the forehead, closing his eyes and taking a deep breath – like Dracula. Then he opened the sweet, fizzy drink and poured some for Daphne, who took a few sips.

‘Mm, it really helps,’ she said and smiled at Ralph as if she was a brave veteran of war saying, ‘It was nothing really.’

‘I rang your house this morning and Ellie told me. What a fandango. But, you know, the greenish tinge to your pallor is quite appealing. And, Lady Jane, you don’t have your usual rosy colouring either.’

Jane longed for some Lucozade, but didn’t ask and it wasn’t offered. She felt ill and fed up. She’d wanted to talk with Daphne and saw how unimportant she became to her friend when Ralph was around. She wanted a handsome man bringing love and bearing gifts. A man to stroke her, a man with a penis to press against her.

‘I have to go,’ she said. ‘See you.’

As she walked past Maurice in the hospital car park, she kicked its side as hard as she could. At home, she told her mother she was going to do her homework and lay on her bed, pulled down her jeans and masturbated. She pictured Ralph naked, shocked by the crushing surge of furious lust that swept her quickly to a shuddering orgasm.

When Nina woke him at eight with green tea, he felt like a drowning man being pulled from the sea. Painful limbs, bitter-tasting mouth. Sleep had hovered just out of reach that night, and at three he’d raided her Greek supply of Stilnox for a few hours of oblivion. Now she made him toast and honey with the crusts cut off, knowing how to tempt, as she’d done when the children were ill. These days she forbade coffee and he was too tired to argue.

He insisted on taking a cab to the hospital, fearing Nina would crowd him out with kindness. From habit he packed his worn leather bag with the usual comforters, including tattered cashmere wrap, book and salted crackers, though they were more like superstitious charms, as his appointment was only to see his surgeon. Unsurprisingly, Mr Goodlove was running late. Plenty of time for thought, slumped in a waiting-room chair, eyes closed. His previous hospital-displacing technique was out of the question. The landscape he usually summoned had transformed from garden of paradise into treacherous hellhole. Where images of the flinty-eyed, wild-haired girl up a tree had been part of his healing, they were now like poison. Yet he couldn’t prevent himself returning, addict-like, to the thoughts that had kept him going through his therapies.

His mobile rang. ‘Jeb’ showed on the screen. He answered, if only for the distraction. Jeb sounded wired, as though he’d drunk five espressos. ‘Not guilty is the way forward. Riskier but cleaner. We’ll focus on Daphne as a bit “complicated”. Loopy, in other words. A difficult life with addictions, rehab, evictions and so on. Yes, you were friends when she was a kid – friends with her parents and brother too. You took her and her friends out to the cinema or the occasional theatre. Not swimming. Meals with your family. Wholesome stuff. You were a happily married man with young children, a blossoming career. We’ll go over all this. The trip to Greece was a chore – a favour to her parents. You can’t understand why she’d make this up after all this time. Envy perhaps?’ Ralph let Jeb witter on with his comforting clichés. ‘There’s at least another week or two for the CPS to get back, but I can’t imagine… Anyway, we cross each bridge. OK, Boydie? Chin up. Got to go.’

It was almost two hours before he went into Mr Goodlove’s office and the doctor apologised for the delay, gesturing for him to sit down. If he did know about Ralph’s disgrace, he gave no sign. Unlike all the nursing staff who used his Christian name, Ralph appreciated that his surgeon called him Mr Boyd. On the desk was a black and white photograph of an intelligent-looking young man. ‘Your son?’ Ralph attempted a social nicety, hoping it would act like a fire blanket to his smouldering fear.

‘Yes. Christopher.’ He smiled. ‘He died five years ago.’ Impressively, the medic kept eye contact. We are all walking around with invisible weights and chains, thought Ralph.

Mr Goodlove was straightforward, but not ruthless, respecting a patient’s terror while not pandering to it. The scan showed the chemotherapy wasn’t working, he said. There was no point in continuing; the chemicals were only weakening his whole system. The disease was in the lymph nodes. And perhaps it had spread to the bones, but that would need a different scan. As things stood, there was little the NHS could do any more. A couple of trials using hormone treatment were going ahead soon. If he was interested, he could certainly join one. If he fulfilled the requirements. Of course, he wouldn’t know if he was taking the drugs or a placebo, but exciting work was being done. At the very least, it was a way of offering something back. ‘What would you like to do?’

‘I fear I have very little choice.’ He tried to emulate Mr Goodlove’s dignity, though his brain was cloudy with dread. They spoke about pain relief. Morphine patches and syrup. Palliative care. A Macmillan nurse. And that was that.

Ralph went home and didn’t tell Nina. He didn’t want panicked sons flying in from abroad wanting deathbed speeches before it was time. He wasn’t dead yet. Pretending his exhaustion resulted from a treatment, he went straight to bed. Nina had changed the sheets and he lay in their cool cleanness, watching the drawn curtains billowing gently from the half-open window. She brought him some plain rice and stewed apple on a tray with a rosebud from the garden in a glass. He ate all the food before falling into opaque, dreamless sleep.

He slept for several hours and woke feeling incongruously invigorated. Perhaps a death sentence is like that, he thought. It brings you back to life. He shut the window on the darkening skies and the smells of incipient autumn – leaf mould and what he imagined were musky squirrel nests.

It was now afternoon, but he decided to treat it like a second morning. Cup of tea, shower, painkillers for the twinges and clothes for action: jeans (belted two holes tighter now), Chelsea boots, a canvas jacket. Nina was at a table in the sitting room painting one of her minuscule abstracts – so small he could hardly make it out. She jumped up, quickly washing the paintbrush in a tin cup. Yes, he was hungry. She started to prepare an omelette – aux fines herbes , as he liked, with tarragon and chives. Slightly runny in the middle. Nina didn’t eat, but sat companionably at the kitchen table, reproaching him mildly when he drank a glass of red wine.

‘I’ve spoken with all the children again today,’ she said. ‘I explained that it’s a misunderstanding. But Jason wants to hear from you, to understand exactly what happened. He asked if you can call him back later. Alexander sent you lots of love. He said, “Of course Dad’s innocent.”’ She shot an enquiring glance and he offered back a small smile of confirmation. ‘And Lucia is actually coming over. Quite soon,’ she said. ‘She and Bee are in London for the day. You need to explain a little bit to her. She’s been upset. You know…’ She left it hanging and then talked of minor family things: Alexander was moving house in Seattle (she suspected a girlfriend was involved but he wasn’t saying); little Sydney’s new nursery school in Madrid. He admired her delicacy for not quizzing him on the hospital. Nor did she mention that this evening was Ed’s birthday and that they weren’t going. He knew she had cancelled their anniversary party in a few weeks’ time, putting it down to hospital schedules rather than possible court sessions. She understood that you don’t always have to hit things head-on. He liked this quality, though a tremor of guilt and dread passed through him like vibrations from a distant earthquake.

Читать дальше