“Yeah? What else?”

“I’d like to see you lick him.”

“What is this, entertainment?”

I’d gone over to her house, and she was lying on the sofa in the living room, a red corduroy dressing gown folded around her and a magazine in her lap. She stretched now, like a cat, and beckoned me over to her. I said to hell with that, I had too much on my mind. She nodded, watched me a while, where I was walking around, and said: “I don’t care what it costs. If it breaks me I don’t care. I’ve been a piker long enough. You’re going to lick him, and down to the last dime I’ll back you up.”

So we kept him, and I settled down to one damned thing after another that cost fifty dollars an hour to fix, shop charges extra. I learned the difference between a twist-off and a wobble-off, and maybe you don’t think that’s something. A twist-off is where they’ve got too much pressure on the bit, the table gives more twist than the pipe can stand, and she pops. A wobble-off is where they’ve got too little pressure on the bit, it gets to spinning faster than the pipe, and she pops. Either way it’s a fishing job, and they lose an hour or more even with the special tools they’ve got, and by the time they’ve caught their fish and rearranged their drill pipe a lot of time is lost before they’re in formation again. There’s plenty of that grief on any well, but a lot depends on the drills they use, with some suited to one formation and others to another, and I could tell from the way the drillers were acting they didn’t think much of Dasso’s ideas on the subject. So that meant I had to have separate huddles with them, and they co-operated, but it all took time, especially as I hated to tip how little I knew. And as soon as I’d licked him on that angle he crossed me on the cement. On an oil well, you’ve got one continuous visitor you don’t hear so much about outside the business. He’s the inspector from the state department of oil and gas, because you’re regulated to the last inch, on account of the way one loused-up job can ruin a lot of surrounding wells, as happened in Mexico, where the richest field in the whole gulf area was drowned in salt water so it’ll never run more than forty per cent of what might have been its capacity.

What they run you ragged about is cementing casing at the right points, and in fact cement is to oil what the gin was to cotton or wing camber to airplanes, something that took them out from behind an eight ball that had had them completely stymied. Because in mountain fields, fresh water flooded the wells long before they hit oil, and in coastal fields salt water, and in coastal-tidal, which pretty well covers California, both. And not only could water flood any well that was drilling, but a wide area as well, so it might easily involve a whole lease, and bankrupt the operator. So in 1903, when the industry had hardly begun, they figured a way to shut it off. They pumped cement down through the casing, with enough pressure back of it to force it up and around, between the pipe and the formation. It worked. It shut off everything, inside and outside, solid as a rock; inside the pipe they drilled the cement out, and went on down to the oil with a nice clean hole that wouldn’t flow oil ruined by salt water when they got to the surface with it. That was the beginning of oil in a big way, and in a few years they made it law most places that a man had to shut off his water with cement whether he wanted to or not. Nowadays they pump through a plug, as they call it, a block of concrete with valves in it made of plastic, so when they’re set with their cement they just drill right through their plug and go on with their hole.

But when the corings began showing water sand, and Mr. Beal, our state man, told me to set my cement, I’d never heard of cement, and once more I had to get busy with the classified phone book and tell a cement outfit to be on deck in the morning. But when I saw Hannah that night she began to roar. “Cement? Why, that contract was let months ago!”

“You know who with, by any chance?”

“But of course! With Acme!”

“Then I’ll ring them up, and tell them to stand by for a call. And call up this other outfit and say I’m sorry, but I don’t know a cement contract from a left-handed monkey wrench, and they needn’t come.”

“Didn’t Dasso tell you?”

“What do you think?”

“You mean he just sat there and let you talk?”

“He’s your sitter, not mine.”

When I finally did pop Dasso on the chin and tell him to get out of there it made no sense, as it was the one time he wasn’t guilty of anything. We were getting deep by that time. Around four thousand, when gas began coming up through the mud, Beal said get connected up with the blowout preventer, so of course that meant nothing to me, but the driller swung his hook out for something that had been on the ground ever since I’d been there, and that looked like a cross between a bell buoy and a slide trombone. He and Dasso and the roughnecks swung it up in the air and over the casing, and for the better part of an hour they were bolting it in place. Then we got going again. Pretty soon we began getting oil, and that was a heartbreak, because Mr. Beal ordered continuous coring, so we’d have a record of all formation penetrated, else we’d have to set and cement more casing. The reason for that was the terms of our permit. From the first pool, our six other wells were taking all we were entitled to, and if we were to put another well down, it had to go further and find oil deeper down. Other wells in the field were tapping that second zone, but whether it extended under our property nobody could be sure, so it came under the head of new development. Everybody knew how it was, so nobody had much to say, and then the driller looked around and wanted to know where were the core heads. There weren’t any. With that it seemed to me I’d had about all I could take. I didn’t really swing on Dasso. My fist seemed to do it, and he hit the dirt and sat blinking at me. Then he took off his glasses and looked. Then I remembered you weren’t supposed to hit a guy with glasses. Then I felt like a heel and helped him up and handed him his hat. Then I went over to the shack and wrote his time. Then I went back and rang up the service company that kept our stuff in shape, and they said Mr. Dasso had already phoned, and the truck was on its way over with the core heads. So of course that made me feel great. Instead of going over to the crew, who had heard me at the phone, I went over to the wire fence to get my face set again. Rohrer was there, and I knew he had seen it. “Well, kid, I think things’ll be better now.”

“That I wonder about.”

“It was due, and overdue, and your gang’ll respect you for it.”

“They might, if it didn’t so happen that when I rang the service shop it turned out Dasso had already done what I fired him for not doing, and I never knew any gang yet that bought it when somebody got the wrong end of the stick.”

“Did he tell you what he’d done? Was he tongue-tied that he couldn’t say it? Did he ever tell you what he was doing, or give you any report you didn’t crowbar out of him? Don’t you worry about that gang. They know if it wasn’t this it had to be something else, and it didn’t make much difference what, or if all the fine points were right or not. He had it coming. You’ll get along better.”

We got along so much better it was no comparison, and I began telling myself I’d learned more about oil than I’d realized. Stuff that we needed began coming on time, instead of three hours late like when Dasso had charge, the fishing was cut to half what it had been, and counting all cementing, setting of new casing, and everything else we had to do, we were making half again as good time. Hannah was dancing all over her living room whenever I saw her, and wanted to open champagne for me. I said let me do my work. At fifty five hundred feet we began to get gas, and I got so nervous I hardly left the place, but slept on the desk that was in the shack, and got up every hour or two, to keep track of what was going on. Pretty soon our corings came up with kind of a combined smell of coal tar, crackcase drainings, and low tide on a mud flat, a stink you could smell ten feet, that was prettier than anything Chanel ever put out. It meant oil, and this time we could keep it, with no need to go to a deeper level. Everything had that feeling in the air. The state man said take it easy, and we slowed to half speed. Scouts, supers, and engineers began dropping around from other wells, so at any time there’d be eight or a dozen of them standing around, waiting. The super from Luxor dropped over, and we picked out where the new gauging tanks would be put: right over from the head of our double row of six, the first of a new double row of six, as we hoped, with the foundations all in line. I got out my transit and set stakes for the concrete. I ordered a Christmas tree.

Читать дальше

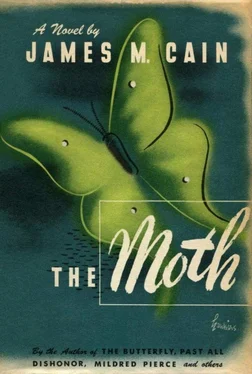

![Джеймс Кейн - Почтальон всегда звонит дважды [сборник litres]](/books/412339/dzhejms-kejn-pochtalon-vsegda-zvonit-dvazhdy-sborni-thumb.webp)