The two of us kept silent, drinking our drinks and thinking our separate thoughts.

‘Do you mind if I ask you one thing?’ I asked. ‘Or, more precisely, two things.’

‘Go ahead,’ she said. ‘I imagine you’re going to ask me what I wished for that time. That’s the first thing you want to know.’

‘But it looks as though you don’t want to talk about that.’

‘Does it?’

I nodded.

She put the coaster down and narrowed her eyes as if staring at something in the distance. ‘You’re not supposed to tell anybody what you wished for, you know.’

‘I won’t try to drag it out of you,’ I said. ‘I would like to know whether or not it came true, though. And also – whatever the wish itself might have been – whether or not you later came to regret what it was you chose to wish for. Were you ever sorry you didn’t wish for something else?’

‘The answer to the first question is yes and also no. I still have a lot of living left to do, probably. I haven’t seen how things are going to work out to the end.’

‘So it was a wish that takes time to come true?’

‘You could say that. Time is going to play an important role.’

‘Like in cooking certain dishes?’

She nodded.

I thought about that for a moment, but the only thing that came to mind was the image of a gigantic pie cooking slowly in an oven at low heat.

‘And the answer to my second question?’

‘What was that again?’

‘Whether you ever regretted your choice of what to wish for.’

A moment of silence followed. The eyes she turned on me seemed to lack any depth. The desiccated shadow of a smile flickered at the corners of her mouth, suggesting a kind of hushed sense of resignation.

‘I’m married now,’ she said. ‘To a CPA three years older than me. And I have two children, a boy and a girl. We have an Irish setter. I drive an Audi, and I play tennis with my girlfriends twice a week. That’s the life I’m living now.’

‘Sounds pretty good to me,’ I said.

‘Even if the Audi’s bumper has two dents?’

‘Hey, bumpers are made for denting.’

‘That would make a great bumper sticker,’ she said. ‘“Bumpers are for denting.”’

I looked at her mouth when she said that.

‘What I’m trying to tell you is this,’ she said more softly, scratching an earlobe. It was a beautifully shaped earlobe. ‘No matter what they wish for, no matter how far they go, people can never be anything but themselves. That’s all.’

‘There’s another good bumper sticker,’ I said. ‘“No matter how far they go, people can never be anything but themselves.”’

She laughed aloud, with a real show of pleasure, and the shadow was gone.

She rested her elbow on the bar and looked at me. ‘Tell me,’ she said. ‘What would you have wished for if you had been in my position?’

‘On the night of my twentieth birthday, you mean?’

‘Uh-huh.’

I took some time to think about that, but I couldn’t come up with a single wish.

‘I can’t think of anything,’ I confessed. ‘I’m too far away now from my twentieth birthday.’

‘You really can’t think of anything?’

I nodded.

‘Not one thing?’

‘Not one thing.’

She looked into my eyes again – straight in – and said, ‘That’s because you’ve already made your wish.’

‘But you had better think about it very carefully, my lovely young fairy, because I can grant you only one.’ In the darkness somewhere, an old man wearing a withered-leaf-coloured tie raises a finger. ‘Just one. You can’t change your mind afterwards and take it back.’

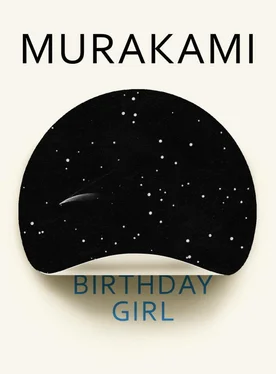

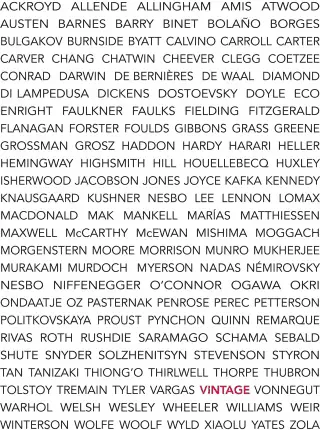

In 1978, Haruki Murakamiwas 29 and running a jazz bar in downtown Tokyo. One April day, the impulse to write a novel came to him suddenly while watching a baseball game. That first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, won a new writers’ award and was published the following year. More followed, including A Wild Sheep Chase and Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, but it was Norwegian Wood, published in 1987, which turned Murakami from a writer into a phenomenon. His books became bestsellers, were translated into many languages, including English, and the door was thrown wide open to Murakami’s unique and addictive fictional universe.

Murakami writes with admirable discipline, producing ten pages a day, after which he runs ten kilometres (he began long-distance running in 1982 and has participated in numerous marathons and races), works on translations, and then reads, listens to records and cooks. His passions colour his non-fiction output, from What I Talk About When I Talk About Running to Absolutely On Music, and they also seep into his novels and short stories, providing quotidian moments in his otherwise freewheeling flights of imaginative inquiry. In works such as The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, 1Q84 and Men Without Women, his distinctive blend of the mysterious and the everyday, of melancholy and humour, continues to enchant readers, ensuring Murakami’s place as one of the world’s most acclaimed and well-loved writers.

@vintagebooks

penguin.co.uk/vintage

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781473563810

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

VINTAGE

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Haruki Murakami 2002

English translation copyright © Jay Rubin 2003, 2004

Design © Suzanne Dean

Haruki Murakami has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published by Harvill Secker in 2019

‘Birthday Girl’ originally appeared in English in Harper’s in 2003 and was first published by The Harvill Press in 2004 in the short story collection Birthday Stories , which was first published in Japanese in 2002 with the title Bāsudei sutōrīzu by Chuokoron-Shinsha, Inc., Tokyo.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

penguin.co.uk/vintage