He paused for breath, panting a little. Quichotte waited patiently.

“You also,” Dr. Smile said, stabbing at Quichotte a sudden vehement finger, “you also are a person who is uninterested in your people. You also, going here, going there, going nowhere, you have broken loose of your moorings, isn’t it. Like a boat without a rudder. Like a car without a driver. Where you came from, who you came from, do you think about it? I don’t think so that you do.”

“You are angry,” Quichotte answered gently. “But I am not the reason for your anger.”

“What do you like?” Dr. Smile roared on. “Our food? Our clothes? Our religions? Our ways? I don’t think you are concerned with these things. Am I wrong or right?”

“I own thirteen objects,” Quichotte said, “which open the doors of memory. Some family photographs, a ‘Cheeta Brand’ maachis, a stone head from Gandhara, a hoopoe bird.”

“You are a fool,” Dr. Smile said, and then, like a burst balloon, subsided. “But you are a fool who is going to have a very lucky day. My luck today, however, is bad. However, I will not go to ground like a rat in a hole. I will not vanish like a thief in the night. I will surrender myself, I will pay whatever bail they want, I will wear the damn ankle bracelet, and I will fight. This is America. I will fight and I will win.” His words had a hollow ring, expressing a bravado he did not feel.

“That is an admirable course to follow,” said Quichotte.

“What nobody grasps,” Dr. Smile said with the weariness of a man who carries a burden other people are unwilling to lift, “is that business gets harder all the time. I do things responsibly, through medical personnel, et cetera. But there are gangs now. They threaten my people. You are lucky you quit when you did.”

I didn’t quit, Quichotte remembered. I was dismissed. This also he did not say.

“Crazy names,” Dr. Smile said, his voice receding into a melancholy growl. “Nine Trey Gangsta Bloods. It has no meaning. But they are selling everything out on the street. Heroin, fentanyl, furanyl fentanyl, MDMA, dibutylone. They are irresponsible and unscrupulous. To a medical person, they are anathema. Also they deplete my sales.”

“Can I ask,” Quichotte finally ventured, “why it is that you wished to see me? Why is it a lucky day for me?”

“You are like everyone else,” Dr. Smile said sadly. “Me, me, me.” Nodding with the bruised resignation of a man who only, selflessly, works for the benefit of others, and who goes unappreciated and unloved by the selfish world, he indicated the attaché case he was carrying. “This you will keep safely,” he said. “You have the deposit box with the key, yes?”

“Yes.”

“Keep it there only. Inside you will see little white envelopes. Each envelope is one delivery of InSmile™ spray, to be made once a month, directly into the lady’s personal hand. To this procedure she has agreed.”

“The lady is very unwell?”

“The lady is very important.”

“But she is a person with a medical requirement?”

“She is a person we wish to please.”

“And this is what you want me to do,” Quichotte said. His tone of deflation mirrored his cousin’s. “To please a person who is not sick.”

“Ask me her name,” Dr. Smile said. “Then let’s see what you think.”

When the name was spoken a great radiance opened up in the heavens and flowed down over Quichotte in a cascade of joy. His labors had not been in vain. He had proved himself worthy and now the Grail had manifested herself. He had abandoned reason for the sake of love, accepted the uselessness of worldly knowledge, surrendered his desires and attachments to the world, understood that everything was connected, moved beyond harmony, and now in the Valley of Wonderment the name of the Beloved hung in the air before him as if on a giant flat-screen television. It occurred to him that he loved the man who had caused this miracle to occur.

“I love you,” he said to Dr. Smile.

The doctor, pondering his troubles, was startled and horrified by this remark. “What are you talking?” he demanded.

“I love you,” Quichotte repeated. The radiance was still cascading and now perhaps a celestial choir had begun to sing.

“Men do not talk so to men,” Dr. Smile admonished fiercely. “Yes, of course, there are family I-love-yous, and even between cousins, okay, but the tone of voice is different. It is casual, like air kisses near the cheek. What is this I luuuve you? Less emotion, please. We are not husband and wife.”

But Quichotte in his reverie wanted to say, Can’t you see the radiance descending? Can’t you hear the angels as they sing? The miracle is upon us, and you are the man who has made it so, and how can I react except with openhearted love?

“Tell her,” Dr. Smile said, changing the subject, “that we are making product improvements all the time. We will overcome our present obstacles and proceed. Soon we will have a small tablet, only three millimeters diameter, thirty micrograms. It will be ten times more powerful than the InSmile™ spray. Tell her, if she wishes, this also can be available.”

Then Quichotte’s head swirled, the birds of the park spiraled over him in a phantom dance, and he entered an agon, a great interior struggle, in which his whole being was at war, a battle in which he was at once protagonist and antagonist. The first Quichotte exulted, My love is within my grasp, while the second objected, I am being asked to do a dishonorable thing, and are we not honorable men? The first cried, The miracle is upon me, and I cannot refuse it, and the second replied, She is not sick and this is medicine for the terminally ill. Beside that American oak which was by no means tropical and that Indian cousin who was by no means ethical, a nonsensical verse flowed unbidden through his broken mind.

Under the bam

Under the boo

Under the bamboo tree

He understood, to the best of his capacity, his true nature. He was impure. He was the bam and he was also the boo; the flawed as well as the fine, the honorable and the dishonorable too. He was not Sir Galahad, nor was he meant to be. As the realization dawned it was as if the entire structure of his quest fell away, shriveled and dissolved in that light like a night creature that hates the sun. It had been a delusion, the whole business of needing to be worthy, of needing to make himself worthy of her. All that mattered was this opportunity, knocking. This attaché case was all that mattered. Which made him not a knight but an opportunist, and an opportunist was an altogether lower form of life. Altogether unworthy.

Then a heretical thought occurred. Was it possible, that she, the Beloved, was unworthy too? What he was being asked to do for her was wrong, yet she was asking it. A goddess or a queen did not ask her knight or her hero, who wore her favor on his helmet, to perform immoral tasks. So if she was asking this, then she was no more a queen or a goddess than he was a hero or a knight. Her request and his fulfillment of that request would topple them both off their pedestals and drag them down into the dirt together. And paradoxically, he thought, if she was no longer a queen-goddess, then she was no longer impossible for him, no longer out of his reach. Her fall from purity made her mortal, human, and therefore attainable.

Dr. Smile was saying something. Through the torrent of his thoughts Quichotte heard his cousin say, “Also in every envelope there is Narcan, in case of need. Both in nasal spray form and in auto-injectors.”

Narcan was naloxone, the medication of choice in case of opioid overdose. Auto-injection brought the fastest results: this worked in about two minutes and the effect lasted for thirty to sixty minutes, so multiple doses might be required in the case of a major crisis. Narcan, Quichotte thought, was also the moral salve which made it all right for him to do what he was being asked to do, the shield that would protect the Beloved from self-inflicted harm.

Читать дальше

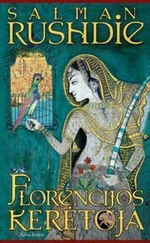

![Ахмед Рушди - Кишот [litres]](/books/431495/ahmed-rushdi-kishot-litres-thumb.webp)