He left Quichotte in the room watching Project Runway and headed for the darkest corner of the Motel 6 parking lot. Here, standing between a pickup truck (a blue Honda Ridgeline Sport AWD, if you must know) and an aging red Hyundai Elantra, he spread his arms and closed his eyes and called upon the realm of the magical. “Grillo Parlante,” he said.

“So, finally he comprehends that he need a friend,” said a voice from the hood of the Elantra. “Cosa vuoi, paisan? What do you wish from me?”

“I get wishes? How many? Three?”

“That is not the way it works,” the cricket said. “The way it works, you ask what you wish, e poi, vedremo. Let’s see if it can be done. There are limits.”

“So,” Sancho said, taking a deep breath, “a driving license, a bank account, a card for the ATM, and money in the bank.”

“Banking is only susceptible to magic at the level of the grande frode, the major fraud,” the cricket said. “Billionaires, politicians, mafiosi. You don’t play in that league. At your level, it’s strictly a cash economy.”

“That’s disappointing,” Sancho said. “Is there maybe a more powerful person I could talk to instead of you? A blue fairy, for example?”

“The blue fairy è una favola,” said the cricket. “It’s a fairy tale. At least at your level. Don’t even think about her. Also, don’t be insulting.”

“Then I’m fucked,” Sancho said.

“How fucked?” the cricket asked. “Why fucked? You’re ungrateful, si. You’re rude, also. You’re poor, of course. But fucked, no. Look in your billfold.”

“I don’t have a billfold.”

“Look in the pocket of your pants. Is there a billfold there or am I full of shit?”

There was something in his pocket. Sancho removed it, in wonderment. It was a cheap brown leather billfold and in it were ten new twenty-dollar bills.

“Two hundred dollars is the maximum possible,” the cricket said. “According to your limits.”

Two hundred dollars, at that moment, felt like a fortune to Sancho. But he was suspicious. “Is this like a conjuring trick?” he asked. “Will it disappear when the trick ends?”

The cricket ignored this contemptible slander. “Is there something else in the billfold?” it asked. Sancho looked again. There was an absolutely real-looking state ID card with his photograph on it, and his signature, or what might be his signature if he ever signed his name, which so far he had never done. “New York State,” the cricket said with a note of pride. “Non è facile, New York State.”

“Thank you,” Sancho said, overwhelmed.

“Driving license, not possible, not even magic can make you a good driver,” the cricket said. “But this is all the ID you require. Now you are truly free,” the cricket said. “And to be human you must have at least la possibilità di libertà. You are trapped in the cash economy, as I told you; this is true, but you have ten Jacksons and an ID card. Great starting point! So a bank account can be procured by non-magical means.”

Sancho shook his head in disbelief.

“The question is,” the cricket asked, “now that you are free, what do you want to do? Where do you want to go?”

“In the long term, I don’t know yet,” Sancho replied. “But in the short term—right now—there’s someone I want to see.”

—

SANCHO IS AT THE DOOR of a modest home in Beautiful, a cream-colored two-story building, with the word WELCOME, in English, sprayed in white paint on a red ground in the small forecourt, below a small OM sign. There is no doorbell. He takes hold of the brass knocker and knocks, twice. After a pause the door is opened by a young woman in her early twenties. Sancho instantly recognizes that something impossible has happened: that this stranger is the perfect woman for him, the girl of his dreams, and fate karma kismet has brought him here to meet his only true love; and he arrives in that same instant at the tragic realization that a dream is just a dream, karma does not come with any guarantees, and this girl whose name he does not know will not be his. Never in a thousand lifetimes. He blushes deeply and cannot speak.

“ Yes?” says the beloved.

He clears his throat and speaks in the voice of despairing adoration. “May I see Mrs. K, the lady of the house.”

“Who are you. Why are you here. Don’t you know better than to intrude at such a time. The whole community is in grief. Are you a journalist.”

“No. Not a journalist. But she asked a question on TV and I need to know her answer. Is there a place for us, she asked. I need to know what she thinks.”

“I know what you want. You want to steal something from her. You want to steal his death and her sadness and make it yours. Go away and get your own sadness and your own death. These things don’t belong to you.”

“I was there. I was in the bar.”

“Many people were in the bar. Nobody prevented it. You also did not prevent it. We are not here to console you for this death. If you have evidence go to police.”

“Are you the lady’s sister? Excuse me but you are very beautiful. Beautiful from Beautiful.” (He can’t help himself.)

“You are an obscene person. I will shut the door now.” (Her scorn destroys him.)

“Please. Forgive me. I only recently arrived in this country. I need to know what it means. How we should live.”

“You are not from here.”

“No. I’m passing through. My name is Sancho.”

“That’s a peculiar name. Okay, let me tell you this, Mr. Sancho. We are all affected. People said to my father, don’t let your daughter work in America anymore, send her home. Maybe I will take that advice now. Nobody can tell the difference, Iranian, Arab, Muslim. Therefore we are not safe. Now Indian Indian families do not want arranged marriages with Indian Americans anymore. Maybe our people will go to Canada. Canada says it will receive us. There is also the question of language. We are Telangana people, our language is Telugu. But we tell each other, do not speak Telugu where others can hear. Telugu, Arabic, Persian, nobody can tell the difference. Therefore we are not safe. That bar was supposed to be a safe place and they were not speaking Telugu to each other but still it was not safe, so nowhere is safe. Have you heard enough? We have lost our tongues. We must be cowardly and tear our own tongues from our mouths.”

“That sucks. But I get it. May I see the lady to express my condolences?”

“This is not that lady’s house. She is not here. You have come to the wrong address.”

“Then what—”

“We are all that lady now. We are all her family. If you are from home, from the country, only recently arrived, then you will surely understand. But this is not your place. This is not your blood.”

“What is your name?”

“Why do you want to know my name?”

“You know my name.”

“What did you call me before?”

“Beautiful from Beautiful.”

“Then that’s my name.”

“I have to go,” Sancho says. “ I have to accompany my father on his last journey. When I’m done with that…”

“I don’t know you,” she says. “And the future? Nobody can see it. Go away.”

The door shuts.

He leaves, simultaneously brokenhearted and elated, but with a new look to him; a sudden determination, which is not the same thing as requited love, but is, at least, something he can take away from the encounter.

—

QUICHOTTE WAS WAITING IN the car, looking displeased. “You are a headstrong child,” he said. “I made it clear that this was an absurd idea, more than absurd, an indecorous deed. If I have brought you here it is because you threatened me with your departure, and I did not bring you into the world to lose you so soon. It is worse than indecorous, what you have done. It is an irrelevance to the great matter which we have in hand, the great enterprise we have undertaken. It is a sidetrack, a blind alley, and none of our business.”

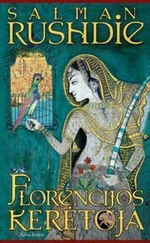

Читать дальше

![Ахмед Рушди - Кишот [litres]](/books/431495/ahmed-rushdi-kishot-litres-thumb.webp)