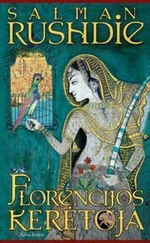

In addition, he had developed an acute fear of flying. He remembered a dream of first falling and then drowning, and was convinced after that that air travel was the most ridiculous of all the fantasies and falsehoods that the comptrollers of the earth tried to inflict on innocent men and women like himself. If an airplane flew, and its passengers reached their destination safely, that was just a question of good luck. It proved nothing. He did not want to die by falling from the sky into water (his dream) or onto land (which would be even less comfortable), and therefore he resolved that if the gods of good health granted him some sort of recovery he would never again board one of those monstrously heavy containers which promised to lift him thirty thousand feet or more above the ground. And he did recover, albeit with a dragging leg, and since then had traveled only by road. He thought sometimes of making a sea journey down the American coast to Brazil or Argentina, or across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe, but he had never made the necessary arrangements, and nowadays his unreliable health and fragile bank account would probably not be able to take the strain of such a voyage. So, a creature of the road he had become, and would remain.

In an old knapsack, carefully wrapped in tissue paper and bubble wrap, he carried with him a selection of modestly sized objects gathered on his travels: a polished “found art” Chinese stone whose patterning resembled a landscape of wooded hills in the mist, a Buddha-like Gandharan head, an upraised wooden Cambodian hand with a symbol of peace in the center of its palm, two starlike crystals, one large, the other small, a Victorian locket inside which he had placed photographs of his parents, three other photographs depicting a childhood in a distant tropical city, a brass Edwardian English cigar cutter made to look like a sharp-toothed dragon, an Indian “Cheeta Brand” matchbox bearing the image of a prowling cheetah, a miniature marble hoopoe bird, and a Chinese fan. These thirteen things were numinous for him. When he arrived at his room for the night he spent perhaps twenty minutes arranging them carefully around his quarters. They had to be placed just so, in the right relationship to one another, and once he was happy with the arrangement, the room immediately acquired the feeling of home. He knew that without these sacred objects placed in their proper places his life would lack equilibrium and he might surrender to panic, inertia, and finally death. These objects were life itself. As long as they were with him, the road held no terrors. It was his special place.

He was lucky that the Interior Event had not reduced him to complete idiocy, like a stumbling, damaged fellow he had once seen who was incapable of anything more demanding than gathering fallen leaves in a park. He had worked as a commercial traveler in pharmaceuticals for many years, and continued to do so in spite of his postretirement age and his incipiently unstable, unpredictably capricious, increasingly erratic, and mulishly obsessional cast of mind, because of the kindliness of the aforementioned wealthy cousin, R. K. Smile, M.D., a successful entrepreneur, who, after seeing a production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman on TV, had refused to fire his relative, fearing that to do so would hasten the old fellow’s demise. *

Dr. Smile’s pharmaceutical business, always prosperous, had recently catapulted him to billionaire status because of his Georgia laboratories’ perfection of a sublingual spray application of the pain medication fentanyl. Spraying the powerful opioid under the tongue brought faster relief to terminal cancer patients suffering from what the medical community euphemistically called breakthrough pain. Breakthrough pain was unbearable pain. The new spray made it bearable, at least for an hour. The instant success of this spray, patented and brand-named as InSmile™, allowed Dr. R. K. Smile the luxury of carrying his elderly poor relation without worrying unduly about his productivity. Strangely, as it happened, Quichotte’s descent toward lunacy—of which one definition is the inability to separate what-is-so from what-is-not-so— for a time did not materially affect his ability to perform his professional duties. In fact, his condition proved to be a positive boon, helping him to present, with absolute sincerity, the shaky case for many of his company’s offerings, believing wholeheartedly in their advertised efficacy and superiority over all their rivals, even though the advertising campaigns were decidedly slanted, and in many cases the products were no better than many similar brands, and in some cases decidedly inferior to the market in general. Because of his blurry uncertainty about the location of the truth-lie frontier, and his personal charm and pleasant manner, he inspired confidence and came across as the perfect promoter of his cousin’s wares.

The day inevitably came, however, as the full extent of his cousin’s delusions became known to him, when Dr. Smile finally put him out to pasture. He gave Quichotte the news in the kindest possible way, flying out personally from General Aviation at Hartsfield-Jackson Airport in his new G650ER to meet Quichotte in Flagstaff, Arizona (pop. 70,320), after receiving a worried call from the director of West Flagstaff Family Medicine, D. F. Winona, D.O., M.B.A., F.A.C.O.F.P., to whom Quichotte had improbably confided during their appointment that he was thinking of escorting the delectable Miss Salma R to the next Vanity Fair Oscars party, after which their clandestine romance would finally become public knowledge. Quichotte and Dr. Smile met at the Relax Inn on Historic Route 66, just four miles from Pulliam Airport. They were an odd couple, Quichotte tall, slow, leg-dragging, and Dr. Smile small, bristling with dynamism, and clearly the boss. “What were you thinking?” he asked, sorrowfully but with a note of finality in his voice, this time I can’t save you, and Quichotte, confronted with his nonsensical statement, replied, “It’s true, I got a little ahead of myself, and I apologize for getting carried away, but you know how lovers are, we can’t help talking about love.” He was using the remote in his room to flick back and forth between a basketball game on ESPN and a true crime show on Oxygen, and his manner struck Dr. Smile as affable but distracted.

“You understand,” Dr. Smile said as gently as he could manage, “that I’m going to have to let you go.”

“Oh, not a problem,” Quichotte replied. “Because, as it happens, I have to embark immediately on my quest.”

“I see,” Dr. Smile said slowly. “Well, I want to add that I am prepared to offer you a lump sum in severance pay—not a fortune, but not a negligible amount—and I have that check here with me to give you. Also, you’ll find that Smile Pharmaceuticals’ pension arrangements are not ungenerous. It is my hope and belief that you’ll be able to manage. Also, any time you find yourself in Buckhead, or, in the summer months, on the Golden Isles, the doors of my homes will always be open. Come and have a biryani with my wife and myself.” Mrs. Happy Smile was a zaftig brunette with a flicked-up hairdo. She was, by all accounts, something of a whiz in the kitchen. It was a tempting offer.

“Thank you,” Quichotte said, pocketing the check. “May I ask, will it be all right to bring my Salma with me when I visit? Once we get together, you see, we will be inseparable. And I am sure she will be happy to eat your wife’s fine biryani.”

“Of course,” Dr. Smile assured him, and rose to leave. “Bring her by all means! There’s one other thing,” he added. “Now that you are retired, and no longer in my employ, it may be useful to me, from time to time, to ask you to perform some small private services for me personally. As my close and trusted family member, I know I will be able to rely on you.”

Читать дальше

![Ахмед Рушди - Кишот [litres]](/books/431495/ahmed-rushdi-kishot-litres-thumb.webp)