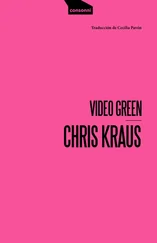

Over breakfast at the Antelope IHOP, Chris informs Sylvère that the flirtatious behavior she shared with Dick the previous night amounts to a “Conceptual Fuck” (21). Because Sylvère and Chris are no longer having sex, Kraus tells us, “the two maintain their intimacy via deconstruction: i.e. they tell each other everything” (21). Chris tells Sylvère that Dick’s disappearance invests the flirtation “with a subcultural subtext she and Dick both share: she’s reminded of all the fuzzy one-time fucks she’s had with men who’re out the door before her eyes are open” (21). Sylvère, “a European intellectual, who teaches Proust, is skilled in the analysis of love’s minutiae” (25). He buys Chris’ interpretation of the evening, and for the next four days the two do little else but talk about Dick.

The couple starts collaborating on billets-douxto Dick. At first they just share the letters with each other, but as the pile grows to 50 then 80 then 180 pages, they begin discussing some kind of Sophie Calle-like art piece, in which they would present the manuscript to Dick. Perhaps hang the letters on the cactus and shrubs in front of his house and videotape his reaction. Perhaps Sylvère should read from the letters during his Critical Studies Seminar when he visits Dick’s school in March? “It seems to be a step towards the kind of confrontational performing art that you’re encouraging,” he writes in one of his darker notes to Dick (43). When Chris finally does give the letters to Dick, “things get pretty weird” (162). But by that time, the letters have become an art form in and of themselves, a means to something that has almost nothing to do with Dick.

“Think of language as a signifying chain,” Chris writes, referencing Lacan (233). And here you can literally see the signifying chain at work, as Chris’ letters to Dick open up to include essays on Kitaj, schizophrenia, Hannah Wilke, the Adirondacks, Eleanor Antin, and Guatemalan politics. “Dear Dick,” she writes at one point, “I guess in a sense I’ve killed you. You’ve become Dear Diary…” (90).

If Chris has metaphorically “killed” Dick by turning him into “Dear Diary,” Dick—when he finally writes back—erases Chris. Despite the fact that he appears to have had sex with her at least twice and has shared several lengthy conversations (“long distance bills fill the gaps left in my diaries,” she writes at one point, 230), he continually maintains that he doesn’t know her and that her obsession with him is based solely on “two genial but not particularly intimate or remarkable meetings spread out over a period of years” (260). At the close of the book, as almost every reviewer notes, Dick finally responds by writing directly to Sylvère but not Chris. “In the letter,” Anne-Christine d’Adesky writes,

he misspells her name as Kris, and seems mostly concerned with salvaging his damaged relationship with Sylvère. He expresses regret, discomfort, and anger at being the objet d’amourin their private game and clearly hopes they won’t publish the correspondence as is. ‘I do not share your conviction that my right to privacy has to be sacrificed for the sake of that talent,’ he tells Lotringer. To Chris, he is more curt, sending only a xeroxed copy of the letter he wrote to her husband. It’s a breathtaking act of humiliation, an unambiguous Fuck You.

But it’s also the appropriate literary conclusion to an adventure that was to some degree initiated by Sylvère. The first love letter in the book was written not by Chris but by her husband. And one of the things the “novel” unveils is the degree to which women in the classic Girardian triangle function as a conduit for a homosocial relationship between men as noted by Sedgwick. “Every letter is a love letter,” Lotringer writes at one point, and certainly his first letter to Dick reveals a desire for intimacy that exceeds the usual hetero-friendly-professional correspondence. “It must be the desert wind that went to our heads that night,” he writes, “or maybe the desire to fictionalize life… We’ve met a few times and I’ve felt a lot of sympathy towards you and a desire to be closer…” (26). The homosocial tone of the letter, as well as Sylvère’s fear that he sounds like a love-struck girl sets up “the game” as one of competition and intimacy between men. No wonder Chris—whose crush on Dick supposedly initiates the adventure—feels “reactive…the Dumb Cunt, a factory of emotions evoked by all the men” (27). When Dick finally writes, he reinforces Chris’ peripheral position. Ignoring everything that has passed between Dick and Chris, he responds to Sylvère’s initial letter to him, in language which illustrates—as d’Adesky notes—that he’s “mostly concerned with salvaging his damaged relationship with Sylvère.”

On the simplest level, then, I Love Dick is a more complicated piece of work than the reviews would indicate. Through the use of letters, taped phone conversations, and written exchanges between Chris and her husband, it deconstructs the classic heterosexual love triangle and lays bare the degree to which—even in the most enlightened circles—women continue to function as an object of exchange. By saying this, however, I don’t mean that it’s simply another illustration of Eve Sedgwick’s arguments in Between Men . Sylvère and Chris are too theoretically savvy to unproblematically present text/language as a transparency through which the real might be read. It’s never clear if the style of Sylvère’s letter is dictated by his feelings for Dick or by his awareness that the “form dictates” certain expressions of sentiment (67). What is clear is that “the real” is not exactly what interests Chris. “The game is real,” she tells Dick in her first letter, “or even better than, reality, and better than is what it’s all about” (28). Sylvère thinks Chris’ evocation of the hyper-real here is “too literary, too Baudrillardian.” But Chris insists. “Better than,” she writes, “means stepping out into complete intensity” (28). And it’s that intensity which Chris craves.

“Lived experience,” Félix Guattari writes in Chaosophy , “does not mean sensible qualities. It means intensification” (235). And while Kraus doesn’t quote Guattari until late in the text, his presence is already felt in the first letter. In fact, what’s interesting is Chris’ idea that you can somehow use Baudrillard’s notion of the hyper-real, the simulacrum, to get to Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of intensification. And that perhaps is the theoretical drive behind the entire project, as the letters and the simulacrum of a passion which receives little encouragement emerge as the truest and best way outside the virtual gridlock and into Deleuzian rematerialization of experience.

Given that Sylvère and Chris’ stated goals ARE the desire to fictionalize life and to surpass the real, it’s curious that the aspect of I Love Dick that is most frequently discussed in reviews is its connection to the banal, its status as a roman à clef. New York magazine revealed that the “Dick” of the book is Dick Hebdige, and rumor had it that Hebdige tried to block publication of I Love Dick by threatening to sue Kraus for invasion of privacy. As a result of this publicity entirely too much attention has been focused on Dick, who—as d’Adesky notes—remains “a mystery man” in the text itself. The fact that he doesn’t return messages, Chris points out, turns his answerphone, and to some extent the man himself, “into a blank screen onto which we can project our fantasies” (29). In an interview with Giovanni Intra, she has called Dick “every Dick…Uber Dick…a transitional object.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу