—

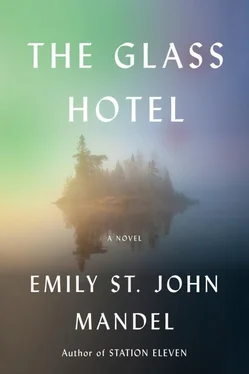

“I can’t quite believe it myself,” he said to his sister, on the phone in 2018, “but I woke up this morning and realized, in February I’ll have been here as the caretaker for ten years.” Difficult to believe, but there it was: ten years of living alone in the staff quarters and playing tour guide to the infrequent potential buyers who arrived by water taxi, a decade of weekly trips to Port Hardy for supplies, cleaning the hotel, mowing the grass, meeting with repairmen when necessary, reading in the afternoons, teaching himself to play piano on the abandoned Steinway in the lobby, walking to the village of Caiette for coffee with Melissa; ten years of wandering by himself in the forest, watching the first pale flowers push through dark earth in the springtime, swimming by the pier in the hottest days of summer and reading on a balcony under blankets in the clear autumn light, sitting alone in the lobby with the lights out for the thrill of winter storms.

“But it seems like you still like it,” she said.

“I do. Very much.”

“Solitary, but not lonely?”

“That’s a fair way of putting it. I wouldn’t have expected this,” he said, “after working in hotels all my adult life, but it turns out I’m happiest when I’m away from other people.”

When he hung up, he left the staff quarters and followed the short path through the forest to the overgrown grass behind the hotel. He let himself in through the back door, making a mental note to sweep and mop the lobby today. Without furniture, the lobby was like a shadowy ballroom, a vast empty space with a panorama of wilderness beyond the glass: inland waters, green shorelines, a pier with no boats.

5

At the pub in Edinburgh, Paul’s tea wasn’t working very well. “I was always ambitious,” he heard himself say, “but I never thought anything would come of it.” Ella nodded, watching him. For how long had he been talking about himself? Did he just fall asleep for a second? He wasn’t sure. It was difficult to stay awake. “All the videos are either beautiful or interesting, but not beautiful or interesting enough, without music added to them.” Did he say this already?

“You seem tired,” Ella said. “Shall we call it a night?”

He glanced at his watch and was startled to find that it was almost one in the morning. She was settling up with the waitress.

“Well, good night, then,” she said, “and good luck, Paul.”

“Do I seem like I need it?” he asked, honestly curious, but she only smiled and wished him good night again. He hated her in that moment, as he rose and left her alone in the bar—the unbearable smugness of the nonaddicted—but of course she wasn’t wrong, he knew he needed luck, he’d OD’d a month ago and woken up in the ER. (“Welcome back, Lazarus,” the doctor had said.) He’d been perfectly functional for nearly a decade on heroin, not just functional but miraculously productive, just a matter of knowing his limits and not being stupid about it, but the problem now was that sometimes the heroin wasn’t heroin anymore, sometimes now it was fentanyl, seeping into the market by mail and by ship, fifty times more potent than heroin and cheaper to produce. He’d been hearing rumors lately of carfentanil in the supply line, which terrified him: one hundred times stronger than fentanyl, approved for the sole purpose of tranquilizing elephants. The other night he’d read about a new rehab facility in Utah, and he’d spent some time on the website, looking at pictures of low white buildings under a desert sky. In a distant, logical way, he knew that going back to rehab wouldn’t be the worst idea. Just do it, get it over with. Outside on the street, the rain had that diffuse quality that Paul associated with both the U.K. and British Columbia, a gentleness about it, coming from all directions at once.

He was almost certain that his hotel was back in the direction of the Royal Mile, which he was almost certain was a left turn at the end of this next street. He was thinking about the Hotel Caiette again, which led to thoughts of Vincent. The street he was on now looked vaguely familiar, but he couldn’t be sure if that was because he was close to the hotel or if it was just that he was going in circles. He stopped walking and sat in a doorway, because he was tired and in his current state the rain wasn’t a problem, sat on the step and rested his head on his arms. Should he try to find Vincent, contact her somehow, offer to share some of his good fortune? No, he needed the money. All of it. I’ve never been able to completely grasp what my responsibilities are, he told her. Sometimes when he spoke to Vincent now, he was the only one talking, while she just watched and listened to him. The doorway was unexpectedly comfortable. He’d just take a little nap, he decided, he’d just rest for a minute and then find his hotel and sleep properly.

But he wasn’t alone. He sensed someone watching him. When he looked up, there was a woman standing just on the other side of the narrow street. She was wearing some sort of uniform, with a long white apron and a handkerchief tied over her hair. She must be a cook from a local restaurant, he decided, perhaps someone who’d just stepped out on a late-night dinner break, but if she was taking a break, she was spending her time very strangely, just staring at him instead of getting something to eat or smoking a cigarette. She looked familiar, she couldn’t possibly be Vincent but—

“Vincent?” he said, and perhaps he’d imagined her, in any event she was gone, but for the rest of his life he would tell the story as if she’d really been there, he’d pull it out like a card trick whenever the subject of ghosts came up—“I was sitting on a step in Edinburgh, and I saw my half sister standing there on the other side of the street, and then she was gone, like she just blinked out. I started looking for her, and what I found out weeks later was that she’d actually died that night, maybe even that minute, thousands of miles away…”—and he would always play it as the real thing, as if he wasn’t hallucinating and the woman he saw was really Vincent and Vincent was really a ghost and the ghost was really there on the street with him, whatever that means—what does it mean to be a ghost, let alone to be there, or here ? There are so many ways to haunt a person, or a life—but uncertainty would always pull at him and he could never be sure; later he would wonder if he actually saw her standing there in an apron or if he added the apron to the memory in retrospect when he found out she’d been a cook; and always the question that pulled at him even at that moment, sitting in a doorway in the rain, drifting at the edge of sleep: Did he really see her, standing there on the street? Or was he just drunk and high, lost in a foreign city far from home, delirious with exhaustion and seeing things in the dark?

1

Begin at the end:

Plummeting down the side of the ship

The horizon flipping once, twice, camera flying from my hand

It felt like plunging into shards of ice.

2

No, begin twenty minutes earlier:

“Where were you last night?” Geoffrey asks. “I was looking for you after my shift.” It is December 2018, and we’ve been together for years now, on and off, coming together and then agreeing to be apart. There are certain frictions: he wanted to marry me once, but I decided long ago that I will marry no one and will never again be dependent on another human being; he talks about quitting the ocean and living together somewhere, but I have no desire to return to land. Tonight we’re together, although we were fighting earlier, and he lies beside me in my bed. We’ve been watching my suitcase slide back and forth across the room. This is the third night of heavy weather.

Читать дальше