The Glass Sentence

The Mapmakers Trilogy - 1

S. E. Grove

For my parents and my brother

There can be no scholar without the heroic mind. The preamble of thought, the transition through which it passes from the unconscious to the conscious, is action. Only so much do I know, as I have lived. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not.

The world,—this shadow of the soul, or other me—lies wide around. Its attractions are the keys which unlock my thoughts and make me acquainted with myself. I run eagerly into this resounding tumult.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar,” 1837

IT HAPPENED LONG ago, when I was only a child. Back then, the outskirts of Boston were still farmland, and in the summer I spent the long days out of doors with friends, coming home only when the sun set. We escaped the heat by swimming in Boon’s Stream, which had a quick current and a deep pool.

On one especially warm day in the summer of 1799, July 16, all my friends had arrived at the stream before me. I could hear them shouting as I ran toward the bank, and when they saw me standing at the edge of the best diving spot, they called to urge me on. “Jump, Lizzie, jump!” I stripped down to my linen underclothes. Then I took a running start and jumped. I had no way of knowing that when I landed, it would be in a different world.

I found myself suspended over the pool. With my knees curled up and my arms wrapped around them, I hung there, looking at the water and at the bank near it, unable to move. It was like trying to wake while inside a dream. You want to wake, want to move, but you can’t; your eyes remain closed, your limbs remain stubbornly still. Only your mind is moving, saying, “Get up, get up!” It was just like that, except the dream that would not let go was the world around me.

Everything had gone quiet. I could not even hear my heart beating. Yet I knew that time was passing, and it was passing too quickly. My friends remained motionless while the water around them rushed past in swirling currents at a frightening speed. And then I saw something happening on the banks of the stream.

The grass began growing before my eyes. It grew steadily, until it reached the height that it normally reached in late summer. Then it began to wilt and brown. The leaves on the trees by the banks of the stream turned yellow and orange and red; before long, they had faded and fluttered to the ground. The light around me shone dully gray, as if stuck between day and night. As the leaves began to fall, the light grew dimmer. The field turned a silvery brown as far as I could see and in the next moment transformed itself into a wide, snow-covered expanse. The stream below me slowed and then froze. The snow rose and fell in waves, as it would through the passage of a long winter, and then it began to recede, pulling away from the naked branches and the soil, leaving muddy earth behind it. The ice on the stream broke into pieces and the water once again rushed through it. Beyond the banks of the stream, the ground turned a pale green, as new shoots sprang up through the soil, and the trees appeared to grow a verdant lace at their edges. Before too long, the leaves took on their darker summer hue and the grass grew higher. It passed in an instant, but I felt as though I had lived an entire year apart from the world while the world moved on.

Suddenly, I dropped. I landed in Boon’s Stream and heard, once again, all the sounds of the world around me. The stream gurgled and splashed, and my friends and I looked at one another in shock. We had all seen the same thing, and we had no idea what had happened.

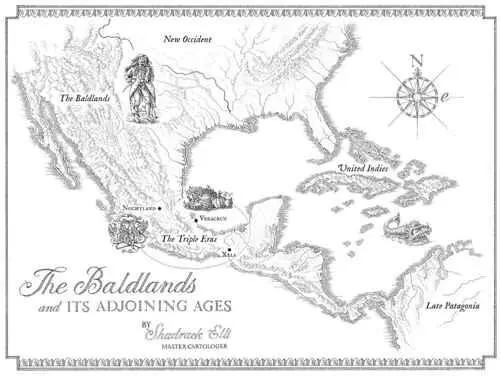

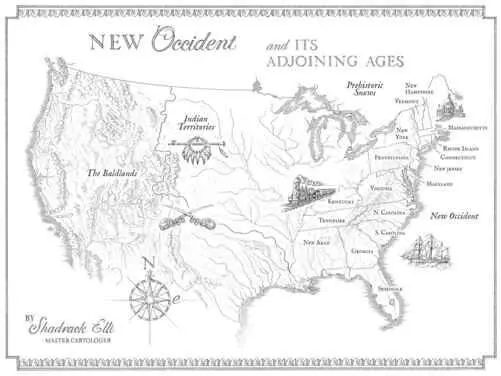

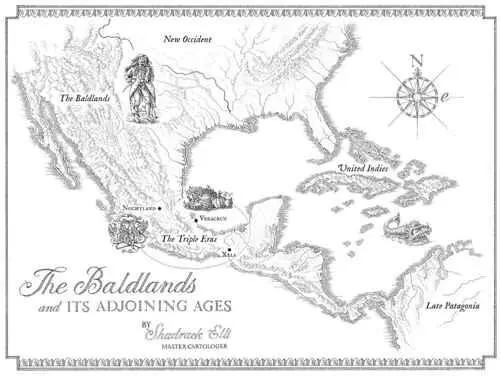

In the days and weeks and months that followed, the people of Boston began to discover the incredible consequences of that moment, even if we could not begin to understand it. The ships from England and France ceased to arrive. When the first sailors who set out from Boston after the change returned, dazed and terrified, they brought back confounding stories of ancient ports and plagues. Traders who headed north described a barren land covered with snow, where all signs of human existence had vanished and incredible beasts known only in myth had suddenly appeared. Travelers who ventured south gave reports so varied—cities of towering glass, and horse raids, and unknown creatures—that no two were the same.

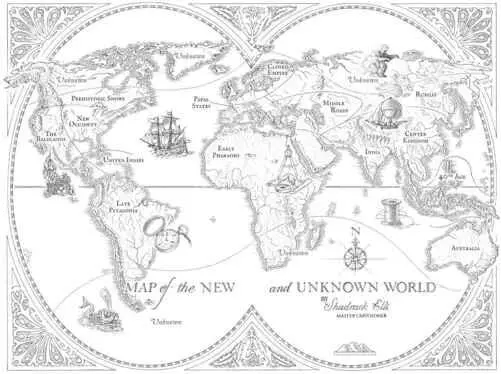

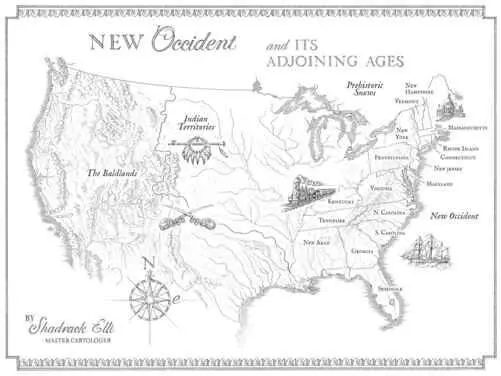

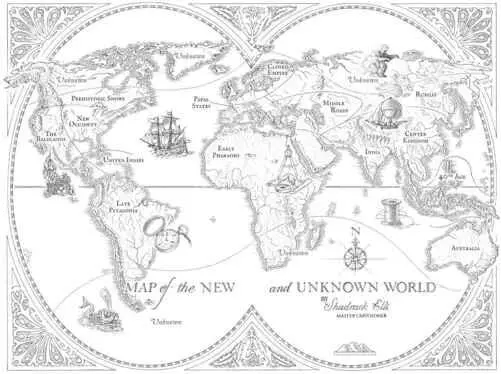

It became apparent that in one terrible moment the various parts of the world had come apart. They were unfastened from time. Spinning freely in different directions, each piece of the world had been flung into a different Age. When the moment passed, the pieces lay scattered, as close to each other in space as they had always been, but hopelessly separated by time. No one knew how old the world truly was, or which Age had caused the catastrophe. The world as we knew it had been broken, and a new world had taken its place.

We called it the Great Disruption.

—Elizabeth Elli to her grandson Shadrack, 1860

1891, June 14: 7-Hour 51

New Occident began its experiment with elected representation full of hope and optimism. But it was soon tainted by corruption and violence, and it became clear that the system had failed. In 1823, a wealthy representative from Boston suggested a radical plan. He proposed that a single parliament govern New Occident and that any person who wished to voice an opinion before it should pay admittance. The plan was hailed—by those who could afford it—as the most democratizing initiative since the Revolution. They had laid the groundwork for the contemporary practice of selling parliament-time by the second.

—From Shadrack Elli’s History of New Occident

THE DAY NEW OCCIDENT closed its borders, the hottest day of the year, was also the day Sophia Tims changed her life forever by losing track of time.

She had begun the day by keeping a close eye on the hour. In the Boston State House, the grand golden clock with its twenty hours hung ponderously over the speaker’s dais. By the time the clock struck eight, the State House was full to capacity. Arranged in a horseshoe around the dais sat the members of parliament: the eighty-eight men and two women rich enough to procure their positions. Facing them sat the visitors who had paid for time to address parliament, and farther back were the members of the public who could afford ground-floor seating. In the cheap seats on the upper balcony, Sophia was surrounded by men and women who had crammed themselves onto the benches. The sun poured in through the tall State House windows, shining off the gilt of the curved balcony rails.

“Brutal, isn’t it?” the woman beside Sophia sighed, fanning herself with her periwinkle bonnet. There were beads of sweat on her upper lip, and her poplin dress was wilted and damp. “I would bet it is five degrees cooler on the ground floor.”

Sophia smiled at her nervously, shuffling her boots against the wooden floorboards. “My uncle is down there. He’s going to speak.”

Читать дальше