“No,” Martin said, thoughtfully, “you’re not wrong.”

They were close to the candlelit tables by now and somebody had turned on the radio inside the house and from a loudspeaker on the terrace music was playing and several couples were dancing. Willard and Linda were dancing together, lightly, not close to each other, barely holding each other. Martin stopped and put his hand on Bowman’s arm to halt him. Bowman was trembling and Martin could feel the little shudders, as though the man were freezing, through the cloth of his sleeve.

“Listen,” Martin said, watching his sister and her husband dance, “I ought to tell them. And I ought to tell the police. Even if nobody could prove anything, you know what that would mean to you around here, don’t you?”

“Yes,” Bowman said, his eyes on the Willards, longing, baffled, despairing. “Ah, do whatever you want,” he said flatly. “It doesn’t make any difference to me.”

“I’m not going to say anything now,” Martin said, sounding harsher than he felt, trying, for Bowman’s sake, to keep the pity out of his voice. “But my sister writes me every week. If I hear that anybody has seen a man outside a window—once—just once …”

Bowman shrugged, still watching the dancers. “You won’t hear anything,” he said. “I’ll stay home at night. I’m never going to learn anything. Why’m I kidding myself?”

He walked away from Martin, robust and demented, a spy lost in a dark country, his pocket crammed with confused intelligence, impossible to decipher. He walked slowly among the dancers, and a moment later, Martin heard his laughter, loud, genial, from the table that was being used as a bar and around which three or four of the guests were standing, including Mr. and Mrs. Winters, who had their arms around each other’s waists.

Martin turned from the group at the bar and looked at his sister and her husband, dancing together on the flagstone terrace to the soft, late-at-night music, that sounded faraway and uninsistent in the open garden. Looking at them with new understanding, he had the feeling that Willard did not feel the need of leading, or Linda of following, that they moved gently and irresistibly together, mysteriously enclosed, beyond danger.

Poor Harry, he thought. But even so, he thought, starting over to Linda to tell her he was ready to go home, even so, tomorrow I’m buying them a dog.

A Biography of Irwin Shaw

Irwin Shaw (1913–1984) was an award-winning American novelist, playwright, screenwriter, and short story writer. His novel The Young Lions (1948) is considered a classic of World War II fiction. From the early pages of the New Yorker to the bestseller lists, Shaw earned a reputation as a leading literary voice of his generation.

Shaw was born Irwin Shamforoff in the Bronx, New York, on February 27, 1913. His parents, Will and Rose, were Russian Jewish immigrants and his father struggled as a haberdasher. The family moved to Brooklyn and barely survived the Depression. After graduating from high school at the age of sixteen, Shaw worked his way through Brooklyn College, where he started as quarterback on the school’s scrappy football team.

“Discovered” by a college teacher (who later got him his first assignment, writing for the Dick Tracy radio serials), Shaw became a household name at the age of twenty-two thanks to his first produced play, Bury the Dead . This 1935 Broadway hit—still regularly produced around the world—is a bugle call against profit-driven barbarity. Offered a job as a Hollywood staff scriptwriter, Shaw then contributed to numerous Golden Era films such as The Big Game (1936) and The Talk of the Town (1942). While continuing to write memorable stories for the New Yorker , he also penned The Gentle People (1939), a play that was adapted for film four different times.

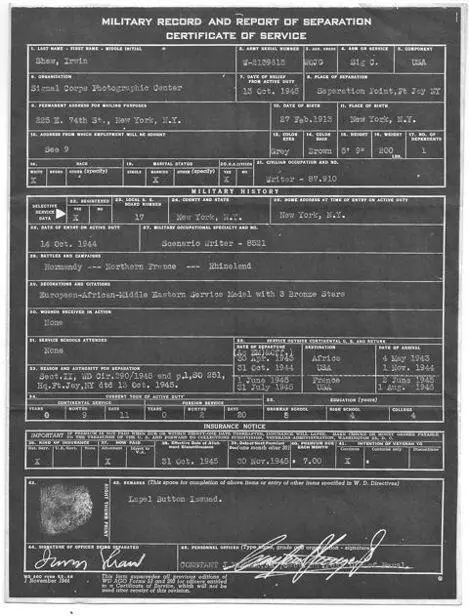

World War II altered the course of Shaw’s career. Refusing a commission, he enlisted in the army, and was shipped off to North Africa as a private in a photography unit in 1943. After the North African campaign, he served in London during the preparations for the invasion of Normandy. After D-Day, Shaw and his unit followed the front lines and documented many of the most important moments of the war, including the liberations of Paris and the Dachau concentration camp.

The Young Lions (1948), his epic novel, follows three soldiers—two Americans and one German—across North Africa, Europe, and into Germany. Along with James Jones’s From Here to Eternity , Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 , Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead , and The Caine Mutiny by Herman Wouk, The Young Lions stands as one of the great American novels of World War II. In 1958, it was made into a film starring Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift.

In 1951, wrongly suspected of Communist sympathies, Shaw moved to Europe with his wife and six-month-old son. In Paris, he was neighbors with journalist Art Buchwald and friends with the great French writers, photographers, actors, and moviemakers of his generation, including Joseph Kessel, Robert Capa, Simone Signoret, and Louis Malle. In Rome, Shaw gave author William Styron his wedding lunch, doctored screenplays, walked with director Federico Fellini on the Via Veneto, and got the idea for his novel Two Weeks in Another Town (1960).

Finally, he settled in the small Swiss village of Klosters and continued writing screenplays, stage plays, and novels. Rich Man, Poor Man (1970) and Beggerman, Thief (1977) were made into the first famous television miniseries. Nightwork (1975) will soon be a major motion picture. Shaw died in the shadow of the Swiss peaks that had inspired Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain .

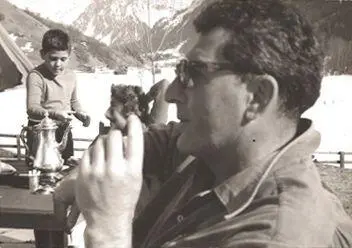

Shaw as a young soldier crossing North Africa from Algiers to Cairo in 1943.

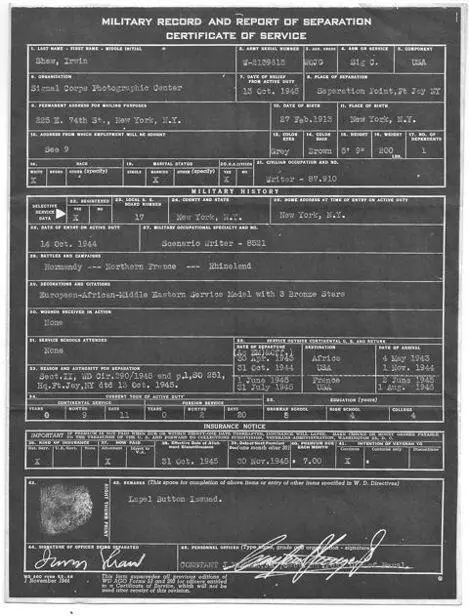

Shaw’s US Army record.

Shaw just after D-Day in Normandy, France, in 1944.

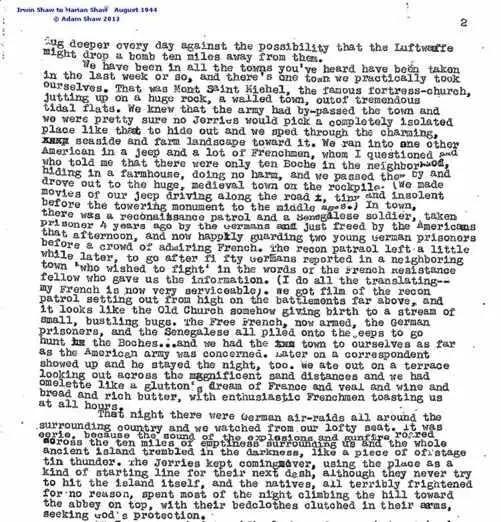

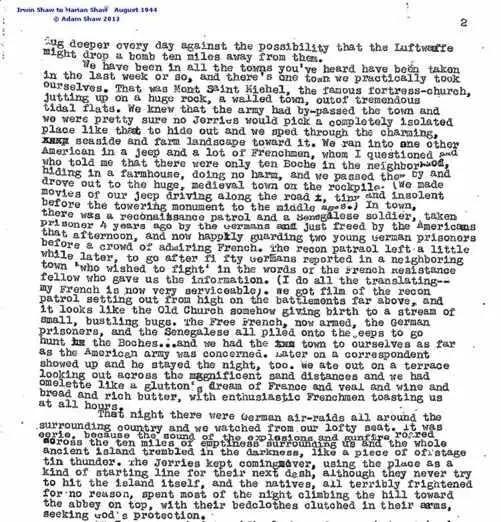

A few weeks after D-Day, Shaw and his Signal Corps film crew liberate Mont Saint-Michel.

A 1944 letter from Shaw to his wife, Marian, describing the “taking” of Mont Saint-Michel, as well as a nerve-wracking night under a cathedral when he almost shot a group of monks, believing them to be Germans.

Shaw as a warrant-officer in Austria in 1945, with Signal Corps Captain Josh Logan (left) and Colonel Anatole Litvak (center), who became his lifelong friends.

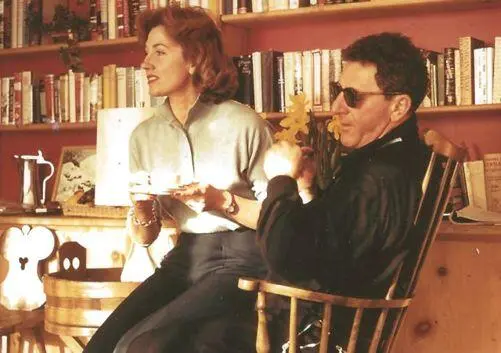

Shaw, Marian, and their son, Adam, on the terrace of the newly built Chalet Mia in Klosters, Switzerland, in 1957.

Читать дальше