Maud will arrive at Semoic Friday night on the 9:40 train. She will have some luggage, so perhaps you should send someone to the train station. I will not belabor the reasons for this sad return…

I know that my daughter is heartbroken at the idea of leaving me, even though her sadness doesn’t show. She will suffer a lot from our separation. She is a poor child who is not lacking in intelligence and fully accepts the severity of her punishment.

I cannot go back to Uderan to accompany her. I would advise you not to stay there too long and not to celebrate your marriage there. Once time has accomplished its work, I will come back one day to sort out a situation that has been much overblown.

I fear you may be mistaken about my feelings. In your eyes I probably don’t respond as I should to the love of a child who adores me. Make no mistake about it: I love her with a tenderness that is so strong and so poignant that I do not dare to broach the subject. There are loves one can never get over, even between a mother and her child, loves that should be lived exclusively. As you know, I am the mother of more than one fatherless child.

There is nothing more for me to say except to wish you happiness. Late engagements can often be marvelous, believe me.

Receive my child, my dear child, with whom the abruptness, the gentleness, and the fragrance of childhood depart from my house. Warm her with the approach of fall, when even nature is sad. I owe myself to this task that is as difficult as it is inept, since it will come to an end with me.

Thank you. I will see you both again soon, when a coming event will dispel all our hard feelings by the promises it will bring.

Marie GRANT-TANERAN

Upon receiving the letter, George Durieux went up to L’Oustaou. There was a chilly fog that morning. He came back slowly at noontime and returned just as slowly after lunch. One by one, he meticulously filled the waiting hours.

He ended up on the station platform well before the train’s arrival. Maud appeared warmly dressed already, as they were in Paris, her features somewhat drawn, with a wide-eyed, anxious look. She waited until George came to her, his eyes fixed on hers.

Her gloved hand was in George’s, both of them inert. But all at once, her staunch look gave way and her hand regained its strength and expressiveness. “Do you have a car? It’s for the suitcase…” She had a big, brand-new suitcase of the kind used by boarders: her mother’s final act of generosity. They had wanted to do things decently…

They left. In the distance, alongside the highway, Uderan lifted up its treetops in the moonlight. “You know that they had seriously committed themselves to a deal?” said Maud, making an effort to address George in a familiar way. “Mother even received the fifty thousand francs. Did you know? What a laugh, all the same!”

Her cheerfulness grated in the cold wind. She snuggled up against him. The car was open, and the wind was howling over their heads. “You’ll see how windy it is at Bordeaux on certain days!” said George.

“At Bordeaux?” Maud asked gently.

“Yes,” he answered, “and as for the fifty thousand francs, don’t worry, they’re already taken care of.”

There was a long silence as she grew accustomed to the idea. “They’ll be awfully happy in Paris. You did that to please them?”

“Yes,” replied George, “why not please them?”

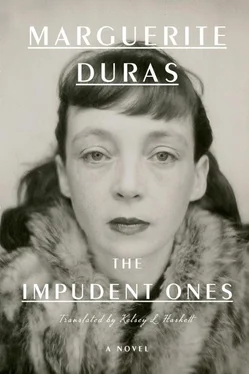

TRANSLATOR’S AFTERWORD

KELSEY L. HASKETT

A study of the place of The Impudent Ones ( Les impudents ) in relation to the totality of Duras’s work, with respect to both narrative style and content, reveals two prominent threads woven throughout the novel: the introduction of a complicated web of family relations that will dominate the entire fabric of Duras’s later work, and the impressive use of descriptive passages—a salient feature that carries over into much of the author’s future writing.

The stylistic differences between this novel, in which Duras deploys her skills as a novelist for the first time, and future novels, have long been acknowledged. Compared to later novels, known for their style dépouillé , in which everything is pared down to the essentials, the use of a more traditional narrative style in The Impudent Ones is evident. Yet even in this debut work, lacking the characteristics of her later inimitable style, Duras’s ability as a writer is irrefutable. Descriptions of specific time and place ring out with great authenticity, while the attention given to the depiction of characters also discloses her keen powers of observation. The extensive development of detail that typifies this beginning novel is perhaps to be expected, given the close relationship between the author and her subject matter, in terms of the setting, the composition of the main family, reflective of her own, and certain people and events that helped inspire her novel, although recast in a new light to form a convincing story that emerges from her imagination. Duras’s fiction generally stems from deeply embedded memories of the past, assimilated and transformed by her psyche, as she crafts them into a novel that becomes a world in itself, a blend of personal experience and creative transformation. By drawing from the start on the resources of her intuitive inner self, as shown in this novel, Duras succeeds in bringing to life a region and a people that strongly impacted her early years, while at the same time insightfully portraying the first of a long line of female characters who are not strictly autobiographical, in the usual sense of the word, but are nevertheless based on her own person.

The principal significance of this first novel, from the standpoint of its content, derives from its relationship to the entirety of Duras’s writings. Not only does The Impudent Ones lay the groundwork for her later “autobiographical fiction,” as it is called, but countless words, phrases, situations, and character types are reproduced throughout Duras’s work, contributing to the obsessive themes that define her as an author. Most important, the family relationships developed here reflect those that she unremittingly shapes and reshapes in succeeding works: the domineering mother who fosters a codependent relationship with her older son to the detriment of her other children, especially her daughter; the cruel, unscrupulous older brother who contributes to his own demise and that of his family; the younger brother, inoffensive, but generally up to no good (especially in the first novel); and the daughter, who suffers from rejection and hostility while seeking love and acceptance in fleeing from her family.

Those who are familiar with Duras’s works will find here the first portrayals of the key family characters, conflicts, and ensuing narratives, in their various iterations, whether in the semi-autobiographical works or inserted less conspicuously in Duras’s fiction. For readers new to her writing, this novel could well be viewed as an invitation to pursue a world-class author whose variations on a central theme focus on questions of family life, rejection, the search for identity, and the quest for an elusive love meant to overcome the dejection of the past and the tragedy of life’s ongoing void, especially for Duras’s female protagonists.

Both textual fragments and narrative details in this initial novel evoke multiple later works. For example, in her second novel, Duras reworks the story developed in The Impudent Ones of a dysfunctional family that “lives in disorder”—the word “disorder” appearing frequently in later novels—while the mother dreams of living a “quiet life,” the title of Duras’s second novel: La vie tranquille . The deep concern shared by the mother and daughter in The Impudent Ones , when the brothers don’t come home at night, is amplified in the third novel, The Sea Wall , where parallel relationships exist between the mother, the favored son, and the daughter. Despite their mutual grievances and their desire to separate in all the works portraying the family, a strong sense of solidarity binds the family members together, right from the very first novel.

Читать дальше