THE OZORA ('BIG SKY') LIMITED EXPRESS TO SAPPORO

E train came out of the long tunnel into the snow country. The earth lay white under the night sky.' The opening lines of Kawabata's Snow Country (set elsewhere, on western Honshu) describe the Ozora, an hour after leaving Hakodate. It was still only five-thirty on that December morning; I had never seen such distances of snow, and after six when the sun came up and yellowed the drifts, giving the snow the harsh glare of desert sand, it was impossible to sleep. I walked up and down the train snapping pictures of everything in sight: it was something no Japanese could possibly object to.

In the dining car, a Japanese man told me, 'This train is called "Big Sky" because Hokkaido is the land of big sky.' I tried to engage him in further conversation, but he cried, 'Please!' and hurried away. There appeared to be no other English-speakers on the train, but while I was eating my breakfast, an American who introduced himself as Chester asked if he could join me. I said fine. I was glad to see him, to reassure myself that I was still capable of assessing strangers and appreciating travel. The mental motion-sickness I had experienced the day before had disturbed me; I had recognized it as fear, and it was an inconvenient state of mind in Japan. Chester was from Los Angeles. He had a handlebar moustache and wore lumberjack's clothes: checked woollen shirt, twill pants, and lace-up boots. He taught English in Hakodate, where he had boarded the train. The people in Hakodate were real nice, but the weather was real bad, his rent was real high, and living was real expensive. He was on his way to Sapporo for the weekend to see a girl he knew. What was I doing?

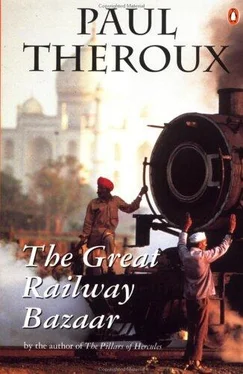

I thought it would be unlucky to lie: a whiff of paranoia had made me superstitious. I told him exactly where I had been, naming the countries; I said that I had been taking notes and that, when I got back to England, I would write a book about the trip and call it The Great Railway Bazaar. And I went further: I said that as soon as he was out of sight I would write down what he said, that the people were real nice and the weather was real bad, and I would describe his moustache.

All this candour had a curious effect: Chester thought I was lying, and when I convinced him I was telling the truth he began speaking in a rather joshing conciliatory way, as if I were crazy and might shortly become violent. It turned out that he had an objection to travel books: he said he didn't want to hurt my feelings but that he thought travel books were useless. I asked him why.

'Because everyone travels,' said Chester. 'So who wants to read about it?'

'Everyone gets laid, too, but that doesn't eliminate screwing as a subject – I mean, people still write about it.'

'Sure, but you take travelling,' he said. 'Your average person in the States thinks nothing about going to Bally. I know lots of people – ordinary middle-class people -who go to really far-out places like Instantbull, Anchor, Taheedy, you name it – my folks are in Oh-sucker right this minute. So they've been there already: who wants to read about it?'

'I don't know, but the fact that they do travel might mean they'd be more interested in reading about it.'

'But they've been there already,' he said obstinately.

'By plane. That's like going in a submarine,' I said. 'A train's different. Look at us: we wouldn't be having this conversation if we were on a plane. Anyway, people don't always see the same things in foreign countries. I've got a theory that what you hear influences – maybe even determines – what you see. An ordinary street can be transformed by a scream. Or a smell might make a horrible place attractive. Or you might see a great Moghul tomb and while you're watching it you'll hear someone say "chickenzola" or "mousehole" and the whole tomb will seem as if it's made out of paste – '

What was this crackpot theory I was inventing for Chester? I couldn't rid myself of the notion that I had to prove to him I was sane. My urge to prove my sanity made me gabble, and my gabbling disproved my claim. Chester squinted at me, sizing me up in a pitying way that made me feel more than ever like Waugh's Pinfold.

'Maybe you're right,' he said. 'Look, I'd love to talk to you but I've got piles of stuff to do.' He hurried away, and for the rest of the trip he avoided me.

The train had crossed a blunt peninsula, from Hakodate to Mori. We made a complete circuit of Uchiura Bay where the newly risen sun received intense magnification from the water and the snow on the shore. We continued along the coast, staying on the main line, which was straight and flat; inland there were mountain shelves and escarpments and the occasional volcano. Mount Tarumae rose on the left as the train began to turn sharply inland, towards Sapporo on the Chitose Line. People in hats with flapping earlaps and bulky coats worked beside the track, lashing poles together to make the skeleton of a snow fence. We left the shore of what was the western limit of the Pacific; within an hour we were near Sapporo, where, from the hills, one can see the blue Sea of Japan. This sea fills the cold Siberian winds with snow; the winds are constant, and the snow in Hokkaido is very deep in December.

But there were not more than three skiers on the train. Later, I asked for an explanation. It was not the skiing season: the skiers would come later, all together, crowding the slopes. The Japanese behaved in concert, giving a seasonal regularity to their pastimes and never jumping the gun. They ski in the skiing season, fly kites in the kite-flying season, sail boats and take walks in parks at other times custom specifies. The snow in Sapporo was perfect for skiing, but I never saw more than two people on a slope, and the ninety-metre ski jump, although covered in hard-packed snow and dusted with powder, was empty and would remain shut until the season opened.

Mr Watanabe, the consulate driver, met me at the station and offered me a guided tour of Sapporo. Sapporo has the look of a Wisconsin city in winter: it had been laid out with a T-square and in its grid of streets lined with dirty snow are used-car lots, department stores, neon signs, plastic hamburger joints, nightclubs, bars. After ten minutes I called off the tour, but it was a feeble gesture – we were stuck in traffic and not moving. Snow began to fall, a few large warning flakes, then gusts of smaller ones.

Mr Watanabe said, 'Snow!'

'Do you like to ski?' I asked.

'I like whisky.'

'Whisky?'

'Yes.' He looked stern. The car ahead moved a few feet; Mr Watanabe followed it and stopped.

I said, 'Mr Watanabe, is that a joke?'

'Yes.'

'You don't like to ski. You like whisky.'

'Yes,' he said. He continued to frown. 'You like ski?'

'Sometimes.'

'We go to ninety-metre ski jump.'

'Not today,' I said. It was darkening; the snowstorm in midmorning had brought twilight to the city.

'This residential,' he said, indicating a row of cuboid houses, each on its own crowded plot and dwarfed by apartment complexes, hotels, and more bars, warming up their neon signs. Hokkaido was the last area in Japan to be developed: Sapporo's commercial centre was new and, with American proportions and the American chill, was not a place that invited a stranger to linger. Mr Watanabe guessed I was bored. He said, 'You want to see tzu?'

'What kind of tzu?'

'Wid enemas.'

'Enemas in cages?'

'Yes. Very big tzu.'

'No thanks.' The traffic had moved another five feet and stopped. The snow had increased, and among the shoppers on the sidewalk I saw three women in kimonos and shawls, their hair fixed into buns with wide combs. They carried parasols and held them against the driving snow as they minced along in three-inch clogs. Mr Watanabe said they were geishas.

Читать дальше