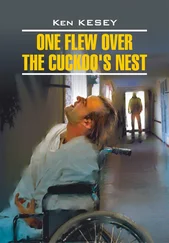

“ ‘Your horses are hungry, that’s what she did say.’ ” He’s enjoying the way the sound rings in the latrine. “ ‘Come sit down beside me, an’ feed them some hay.’ ” He gets a breath, and his voice jumps a key, gaining pitch and power till it’s joggling the wiring in all the walls. “ ‘My horses ain’t hungry, they won’t eat your hay-ay-aeee.’ ” He holds the note and plays with it, then swoops down with the rest of the verse to finish it off. “ ‘So fare-thee-well, darlin’, I’m gone on my way.’ ”

Singing! Everybody’s thunderstruck. They haven’t heard such a thing in years, not on this ward. Most of the Acutes in the dorm are up on their elbows, blinking and listening. They look at one another and raise their eyebrows. How come the black boys haven’t hushed him up out there? They never let anybody raise that much racket before, did they? How come they treat this new guy different? He’s a man made outa skin and bone that’s due to get weak and pale and die, just like the rest of us. He lives under the same laws, gotta eat, bumps up against the same troubles; these things make him just as vulnerable to the Combine as anybody else, don’t they?

But the new guy is different, and the Acutes can see it, different from anybody been coming on this ward for the past ten years, different from anybody they ever met outside. He’s just as vulnerable, maybe, but the Combine didn’t get him.

“ ‘My wagons are loaded,’ ” he sings, “ ‘my whip’s in my hand…’ ”

How’d he manage to slip the collar? Maybe, like old Pete, the Combine missed getting to him soon enough with controls. Maybe he growed up so wild all over the country, batting around from one place to another, never around one town longer’n a few months when he was a kid so a school never got much a hold on him, logging, gambling, running carnival wheels, traveling lightfooted and fast, keeping on the move so much that the Combine never had a chance to get anything installed. Maybe that’s it, he never gave the Combine a chance, just like he never gave the black boy a chance to get to him with the thermometer yesterday morning, because a moving target is hard to hit.

No wife wanting new linoleum. No relatives pulling at him with watery old eyes. No one to care about, which is what makes him free enough to be a good con man. And maybe the reason the black boys don’t rush into that latrine and put a stop to his singing is because they know he’s out of control, and they remember that time with old Pete and what a man out of control can do. And they can see that McMurphy’s a lot bigger than old Pete; if it comes down to getting the best of him, it’s going to take all three of them and the Big Nurse waiting on the sidelines with a needle. The Acutes nod at one another; that’s the reason, they figure, that the black boys haven’t stopped his singing where they would stop any of the rest of us.

I come out of the dorm into the hall just as McMurphy comes out of the latrine. He’s got his cap on and not much else, just a towel grabbed around his hips. He’s holding a toothbrush in his other hand. He stands in the hall, looking up and down, rocking up on his toes to keep off the cold tile as much as he can. Picks him out a black boy, the least one, and walks up to him and whaps him on the shoulder just like they’d been friends all their lives.

“Hey there, old buddy, what’s my chance of gettin’ some toothpaste for brushin’ my grinders?”

The black boy’s dwarf head swivels and comes nose to knuckle with that hand. He frowns at it, then takes a quick check where’s the other two black boys just in case, and tells McMurphy they don’t open the cabinet till six-forty-five. “It’s a policy,” he says.

“Is that right? I mean, is that where they keep the toothpaste? In the cabinet?”

“Tha’s right, locked in the cabinet.”

The black boy tries to go back to polishing the baseboards, but that hand is still lopped over his shoulder like a big red clamp.

“Locked in the cabinet, is it? Well well well, now why do you reckon they keep the toothpaste locked up? I mean, it ain’t like it’s dangerous, is it? You can’t poison a man with it, can you? You couldn’t brain some guy with the tube, could you? What reason you suppose they have for puttin’ something as harmless as a little tube of toothpaste under lock and key?”

“It’s ward policy, Mr. McMurphy, tha’s the reason.” And when he sees that this last reason don’t affect McMurphy like it should, he frowns at that hand on his shoulder and adds, “What you s’pose it’d be like if evahbody was to brush their teeth whenever they took a notion to brush?”

McMurphy turns loose the shoulder, tugs at that tuft of red wool at his neck, and thinks this over. “Uh-huh, uh-huh, I think I can see what you’re drivin’ at: ward policy is for those that can’t brush after every meal.”

“My gaw , don’t you see?”

“Yes, now, I do. You’re saying people’d be brushin’ their teeth whenever the spirit moved them.”

“Tha’s right, tha’s why we—”

“And, lordy, can you imagine? Teeth bein’ brushed at six-thirty, six-twenty — who can tell? maybe even six o’clock. Yeah, I can see your point.”

He winks past the black boy at me standing against the wall.

“I gotta get this baseboard cleaned, McMurphy.”

“Oh. I didn’t mean to keep you from your job.” He starts to back away as the black boy bends to his work again. Then he comes forward and leans over to look in the can at the black boy’s side. “Well, look here; what do we have here?”

The black boy peers down. “Look where?”

“Look here in this old can, Sam. What is the stuff in this old can?”

“Tha’s… soap powder.”

“Well, I generally use paste, but” — McMurphy runs his toothbrush down in the powder and swishes it around and pulls it out and taps it on the side of the can — “but this will do fine for me. I thank you. We’ll look into that ward policy business later.”

And he heads back to the latrine, where I can hear his singing garbled by the piston beat of his toothbrushing.

That black boy’s standing there looking after him with his scrub rag hanging limp in his gray hand. After a minute he blinks and looks around and sees I been watching and comes over and drags me down the hall by the drawstring on my pajamas and pushes me to a place on the floor I just did yesterday.

“There! Damn you, right there! That’s where I want you workin’, not gawkin’ around like some big useless cow! There! There!”

And I lean over and go to mopping with my back to him so he won’t see me grin. I feel good, seeing McMurphy get that black boy’s goat like not many men could. Papa used to be able to do it — spraddle-legged, dead-panned, squinting up at the sky that first time the government men showed up to negotiate about buying off the treaty. “Canada honkers up there,” Papa says, squinting up. Government men look, rattling papers. “What are you — ? In July? There’s no — uh — geese this time of year. Uh, no geese.”

They had been talking like tourists from the East who figure you’ve got to talk to Indians so they’ll understand. Papa didn’t seem to take any notice of the way they talked. He kept looking at the sky. “Geese up there, white man. You know it. Geese this year. And last year. And the year before and the year before.”

The men looked at one another and cleared their throats. “Yes. Maybe true, Chief Bromden. Now. Forget geese. Pay attention to contract. What we offer could greatly benefit you — your people — change the lives of the red man.”

Papa said, “… and the year before and the year before and the year before…”

Читать дальше