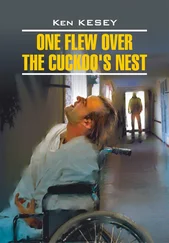

“… hey-ya, hey-ya, come on, come on,” he says, high, fast; “I’m waitin’ on you suckers, you hit or you sit. Hit, you say? well well well and with a king up the boy wants a hit. Whaddaya know. So Comin’ at you and too bad, a little lady for the lad and he’s over the wall and down the road, up the hill and dropped his load. Comin’ at you, Scanlon, and I wish some idiot in that nurses’ hothouse would turn down that frigging music! Hooee! Does that thing play night and day, Harding? I never heard such a driving racket in my life.”

Harding gives him a blank look. “Exactly what noise is it you’re referring to, Mr. McMurphy?”

“That damned radio . Boy. It’s been going ever since I come in this morning. And don’t come on with some baloney that you don’t hear it.”

Harding cocks his ear to the ceiling. “Oh, yes, the so-called music. Yes, I suppose we do hear it if we concentrate, but then one can hear one’s own heartbeat too, if he concentrates hard enough.” He grins at McMurphy. “You see, that’s a recording playing up there, my friend. We seldom hear the radio. The world news might not be therapeutic. And we’ve all heard that recording so many times now it simply slides out of our hearing, the way the sound of a waterfall soon becomes an unheard sound to those who live near it. Do you think if you lived near a waterfall you could hear it very long?”

(I still hear the sound of the falls on the Columbia, always will — always — hear the whoop of Charley Bear Belly stabbed himself a big chinook, hear the slap of fish in the water, laughing naked kids on the bank, the women at the racks… from a long time ago.)

“Do they leave it on all the time, like a waterfall?” McMurphy says.

“Not when we sleep,” Cheswick says, “but all the rest of the time, and that’s the truth.”

“The hell with that. I’ll tell that coon over there to turn it off or get his fat little ass kicked!”

He starts to stand up, and Harding touches his arm. “Friend, that is exactly the kind of statement that gets one branded assaultive. Are you so eager to forfeit the bet?”

McMurphy looks at him. “That’s the way it is, huh? A pressure game? Keep the old pinch on?”

“That’s the way it is.”

He slowly lowers himself back into his seat, saying, “Horse muh-noo-ur.”

Harding looks about at the other Acutes around the card table. “Gentlemen, already I seem to detect in our redheaded challenger a most unheroic decline of his TV-cowboy stoicism.”

He looks at McMurphy across the table, smiling, McMurphy nods at him and tips his head back for the wink and licks his big thumb. “Well sir, of Professor Harding sounds like he’s getting cocky. He wins a couple of splits and he goes to comin’ on like a wise guy. Well well well; there he sits with a deuce showing and here’s a pack of Mar-boros says he backs down. … Whups , he sees me, okeedokee, Perfessor, here’s a trey, he wants another, gets another deuce, try for the big five, Perfessor? Try for that big double pay, or play it safe? Another pack says you won’t. Well well well, the Perfessor sees me, this tells the tale, too bad, another lady and the Perfessor flunks his exams. …”

The next song starts up from the speaker, loud and clangy and a lot of accordion. McMurphy takes a look up at the speaker, and his spiel gets louder and louder to match it.

“… hey-ya hey-ya, okay, next , goddammit, you hit or you sit… comin at ya…!”

Right up to the lights out at nine-thirty.

I could of watched McMurphy at that blackjack table all night, the way he dealt and talked and roped them in and led them smack up to the point where they were just about to quit, then backed down a hand or two to give them confidence and bring them along again. Once he took a break for a cigarette and tilted back in his chair, his hands folded behind his head, and told the guys, “The secret of being a top-notch con man is being able to know what the mark wants , and how to make him think he’s getting it. I learned that when I worked a season on a skillo wheel in a carnival. You fe-e-el the sucker over with your eyes when he comes up and you say, ‘Now here’s a bird that needs to feel tough.’ So every time he snaps at you for taking him you quake in your boots, scared to death, and tell him, ‘Please, sir. No trouble. The next roll is on the house, sir.’ So the both of you are getting what you want.”

He rocks forward, and the legs of his chair come down with a crack. He picks up the deck, zips his thumb over it, knocks the edge of it against the table top, licks his thumb and finger.

“And what I deduce you marks need is a big fat pot to temptate you. Here’s ten packages on the next deal. Hey-yah, comin’ at you, guts ball from here on out. …”

And throws back his head and laughs out loud at the way the guys hustled to get their bets down.

That laugh banged around the day room all evening, and all the time he was dealing he was joking and talking and trying to get the players to laugh along with him. But they were all afraid to loosen up; it’d been too long. He gave up trying and settled down to serious dealing. They won the deal off him a time or two, but he always bought it back or fought it back, and the cigarettes on each side of him grew in bigger and bigger pyramid stacks.

Then just before nine-thirty he started letting them win, lets them win it all back so fast they don’t hardly remember losing. He pays out the last couple of cigarettes and lays down the deck and leans back with a sigh and shoves the cap out of his eyes, and the game is done.

“Well, sir, win a few, lose the rest is what I say.” He shakes his head so forlorn. “I don’t know — I was always a pretty shrewd customer at twenty-one, but you birds may just be too tough for me. You got some kinda uncanny knack , makes a man leery of playing against such sharpies for real money tomorrow.”

He isn’t even kidding himself into thinking they fall for that. He let them win, and every one of us watching the game knows it. So do the players. But there still isn’t a man raking his pile of cigarettes — cigarettes he didn’t really win but only won back because they were his in the first place — that doesn’t have a smirk on his face like he’s the toughest gambler on the whole Mississippi.

The fat black boy and a black boy named Geever run us out of the day room and commence turning lights off with a little key on a chain, and as the ward gets dimmer and darker the eyes of the little birthmarked nurse in the station get bigger and brighter. She’s at the door of the glass station, issuing nighttime pills to the men that shuffle past her in a line, and she’s having a hard time keeping straight who gets poisoned with what tonight. She’s not even watching where she pours the water. What has distracted her attention this way is that big redheaded man with the dreadful cap and the horrible-looking scar, coming her way. She’s watching McMurphy walk away from the card table in the dark day room, his one horny hand twisting the red tuft of hair that sticks out of the little cup at the throat of his work-farm shirt, and I figure by the way she rears back when he reaches the door of the station that she’s probably been warned about him beforehand by the Big Nurse. (“Oh, one more thing before I leave it in your hands tonight, Miss Pilbow; that new man sitting over there, the one with the garish red sideburns and facial lacerations — I’ve reason to believe he is a sex maniac.”)

McMurphy sees how she’s looking so scared and big-eyed at him, so he sticks his head in the station door where she’s issuing pills, and gives her a big friendly grin to get acquainted on. This flusters her so she drops the water pitcher on her foot. She gives a cry and hops on one foot, jerks her hand, and the pill she was about to give me leaps out of the little cup and right down the neck of her uniform where that birthmark stain runs like a river of wine down into a valley.

Читать дальше