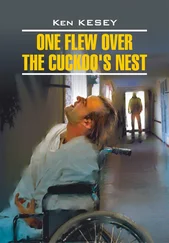

A workman’s eyes snap shut while he’s going at full run, and he drops in his tracks; two of his buddies running by grab him up and lateral him into a furnace as they pass. The furnace whoops a ball of fire and I hear the popping of a million tubes like walking through a field of seed pods. This sound mixes with the whirr and clang of the rest of the machines.

There’s a rhythm to it, like a thundering pulse.

The dorm floor slides on out of the shaft and into the machine room. Right away I see what’s straight above us — one of those trestle affairs like you find in meat houses, rollers on tracks to move carcasses from the cooler to the butcher without much lifting. Two guys in slacks, white shirts with the sleeves turned back, and thin black ties are leaning on the catwalk above our beds, gesturing to each other as they talk, cigarettes in long holders tracing lines of red light. They’re talking but you can’t make out the words above the measured roar rising all around them. One of the guys snaps his fingers, and the nearest workman veers in a sharp turn and sprints to his side. The guy points down at one of the beds with his cigarette holder, and the worker trots off to the steel stepladder and runs down to our level, where he goes out of sight between two transformers huge as potato cellars.

When that worker appears again he’s pulling a hook along the trestle overhead and taking giant strides as he swings along it. He passes my bed and a furnace whooping somewhere suddenly lights his face up right over mine, a face handsome and brutal and waxy like a mask, wanting nothing. I’ve seen a million faces like it.

He goes to the bed and with one hand grabs the old Vegetable Blastic by the heel and lifts him straight up like Blastic don’t weigh more’n a few pounds; with the other hand the worker drives the hook through the tendon back of the heel, and the old guy’s hanging there upside down, his moldy face blown up big, scared, the eyes scummed with mute fear. He keeps flapping both arms and the free leg till his pajama top falls around his head. The worker grabs the top and bunches and twists it like a burlap sack and pulls the trolley clicking back over the trestle to the catwalk and looks up to where those two guys in white shirts are standing. One of the guys takes a scalpel from a holster at his belt. There’s a chain welded to the scalpel. The guy lowers it to the worker, loops the other end of the chain around the railing so the worker can’t run off with a weapon.

The worker takes the scalpel and slices up the front of old Blastic with a clean swing and the old man stops thrashing around. I expect to be sick, but there’s no blood or innards falling out like I was looking to see — just a shower of rust and ashes, and now and again a piece of wire or glass. Worker’s standing there to his knees in what looks like clinkers.

A furnace got its mouth open somewhere, licks up somebody.

I think about jumping up and running around and waking up McMurphy and Harding and as many of the guys as I can, but there wouldn’t be any sense in it. If I shook somebody awake he’d say, Why you crazy idiot, what the hell’s eating you? And then probably help one of the workers lift me onto one of those hooks himself, saying, How about let’s see what the insides of an Indian are like?

I hear the high, cold, whistling wet breath of the fog machine, see the first wisps of it come seeping out from under McMurphy’s bed. I hope he knows enough to hide in the fog.

I hear a silly prattle reminds me of somebody familiar, and I roll enough to get a look down the other way. It’s the hairless Public Relation with the bloated face, that the patients are always arguing about why it’s bloated. “I’ll say he does ,” they’ll argue. “Me, I’ll say he doesn’t; you ever hear of a guy really who wore one?” “Yeh, but you ever hear of a guy like him before?” The first patient shrugs and nods, “Interesting point.”

Now he’s stripped except for a long undershirt with fancy monograms sewed red on front and back. And I see once and for all (the undershirt rides up his back some as he comes walking past, giving me a peek) that he definitely does wear one, laced so tight it might blow up any second.

And dangling from the stays he’s got half a dozen withered objects, tied by the hair like scalps.

He’s carrying a little flask of something that he sips from to keep his throat open for talking, and a camphor hanky he puts in front of his nose from time to time to stop out the stink. There’s a clutch of schoolteachers and college girls and the like hurrying after him. They wear blue aprons and their hair in pin curls. They are listening to him give a brief lecture on the tour.

He thinks of something funny and has to stop his lecture long enough for a swig from the flask to stop the giggling. During the pause one of his pupils stargazes around and sees the gutted Chronic dangling by his heel. She gasps and jumps back. The Public Relation turns and catches sight of the corpse and rushes to take one of those limp hands and give it a spin. The student shrinks forward for a cautious look, face in a trance.

“You see? You see?” He squeals and rolls his eyes and spews stuff from his flask he’s laughing so hard. He’s laughing till i think he’ll explode.

When he finally drowns the laughing he starts back along the row of machines and goes into his lecture again. He stops suddenly and slaps his forehead — “Oh, scatterbrained me!” — and comes running back to the hanging Chronic to rip off another trophy and tie it to his girdle.

Right and left there are other things happening just as bad — crazy, horrible things too goofy and outlandish to cry about and too much true to laugh about — but the fog is getting thick enough I don’t have to watch. And somebody’s tugging at my arm. I know already what will happen: somebody’ll drag me out of the fog and we’ll be back on the ward and there won’t be a sign of what went on tonight and if I was fool enough to try and tell anybody about it they’d say, Idiot, you just had a nightmare; things as crazy as a big machine room down in the bowels of a dam where people get cut up by robot workers don’t exist.

But if they don’t exist, how can a man see them?

It’s Mr. Turkle that pulls me out of the fog by the arm, shaking me and grinning. He says, “You havin’ a bad dream, Mistuh Bromden.” He’s the aide works the long lonely shift from 11 to 7, an old Negro man with a big sleepy grin on the end of a long wobbly neck. He smells like he’s had a little to drink. “Back to sleep now, Mistuh Bromden.”

Some nights he’ll untie the sheet from across me if it’s so tight I squirm around. He wouldn’t do it if he thought the day crew knew it was him, because they’d probably fire him, but he figures the day crew will think it was me untied it. I think he really does it to be kind, to help — but he makes sure he’s safe first.

This time he doesn’t untie the sheet but walks away from me to help two aides I never saw before and a young doctor lift old Blastic onto the stretcher and carry him out, covered with a sheet — handle him more careful than anybody ever handled him before in all his life.

Come morning, McMurphy is up before I am, the first time anybody been up before me since Uncle Jules the Wallwalker was here. Jules was a shrewd old white-haired Negro with a theory the world was being tipped over on its side during the night by the black boys; he used to slip out in the early mornings, aiming to catch them tipping it. Like Jules, I’m up early in the mornings to watch what machinery they’re sneaking onto the ward or installing in the shaving room, and usually it’s just me and the black boys in the hall for fifteen minutes before the next patient is out of bed. But this morning I hear McMurphy out there in the latrine as I come out of the covers. Hear him singing! Singing so you’d think he didn’t have a worry in the world. His voice is clear and strong slapping up against the cement and steel.

Читать дальше