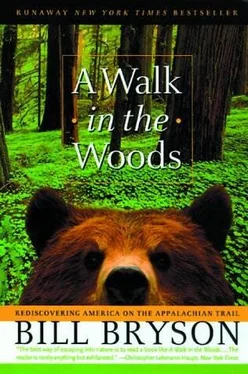

Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Walk In The Woods

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Walk In The Woods: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Walk In The Woods»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Walk In The Woods — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Walk In The Woods», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The hike to the top was steep, hot, and seemingly endless, but Worth the effort. The open, sunny, fresh-aired summit of Greylock is crowned with a large, handsome stone building called Bascom Lodge, built in the 1930s by the tireless cadres of the Civilian Conservation Corps. It now offers a restaurant and overnight accommodation to hikers. Also on the summit is a wonderful, wildly incongruous lighthouse (Greylock is 140 miles from the sea), which serves as the Massachusetts memorial for soldiers killed in the First World War. It was originally planned to stand in Boston Harbor but for some reason ended up here.

I ate my lunch, treated myself to a pee and a wash in the lodge, and then hurried on, for I still had eight miles to go and had a rendezvous arranged with my wife at four in Williamstown. For the next three miles, the walk was mostly along a lofty ridgeline connecting Greylock to Mount Williams. The views were sensational, across lazy hills to the Adirondacks half a dozen miles to the west, but it was really hot. Even up here the air was heavy and listless. And then it was a very steep descent-3,000 feet in three miles-through dense, cool green woods to a back road that led through exquisitely pretty open countryside.

Out of the woods, it was sweltering. It was two miles along a road totally without shade and so hot I could feel the heat through the soles of my boots. When at last I reached Williamstown, a sign on a bank announced a temperature of 97. No wonder I was hot. I crossed the street and stepped into a Burger King, our rendezvous point. If there is a greater reason for being grateful to live in the twentieth century than the joy of stepping from the dog’s breath air of a really hot summer’s day into the crisp, clean, surgical chill of an air-conditioned establishment, then I really cannot think of it.

I bought a bucket-sized Coke and sat in a booth by the window, feeling very pleased. I had done seventeen miles over a reasonably challenging mountain in hot weather. I was grubby, sweat streaked, comprehensively bushed, and rank enough to turn heads. I was a walker again.

In 1850, New England was 70 percent open farmland and 30 percent woods. Today the proportions are exactly reversed. Probably no area in the developed world has undergone a more profound change in just a century or so, at least not in a contrary direction to the normal course of progress.

If you were going to be a farmer, you could hardly choose a worse place than New England. (Well, the middle of Lake Erie maybe, but you know what I mean.) The soil is rocky, the terrain steep, and the weather so bad that people take actual pride in it. A year in Vermont, according to an old saw, is “nine months of winter followed by three months of very poor sledding.”

But until the middle of the nineteenth century, farmers survived in New England because they had proximity to the coastal cities like Boston and Portland and because, I suppose, they didn’t know any better. Then two things happened: the invention of the McCormick reaper (which was ideally suited to the big, rolling farms of the Midwest but no good at all for the cramped, stony fields of New England) and the development of the railroads, which allowed the Midwestern farmers to get their produce to the East in a timely fashion. The New England farmers couldn’t compete, and so they became Midwestern farmers, too. By 1860, nearly half of Vermont-born people-200,000 out of 450,000-were living elsewhere.

In 1840, during the presidential election campaign, Daniel Webster gave an address to 20,000 people on Stratton Mountain in Vermont. Had he tried the same thing twenty years later (which admittedly would have been a good trick, as he had died in the meantime) he would have been lucky to get an audience of fifty. Today Stratton Mountain is pretty much all forest, though if you look carefully you can still see old cellar holes and the straggly remnants of apple orchards clinging glumly to life in the shady understory beneath younger, more assertive birches, maples, and hickories. Everywhere throughout New England you find old, tumbledown field walls, often in the middle of the deepest, most settled-looking woods-a reminder of just how swiftly nature reclaims the land in America.

And so I walked up Stratton Mountain on an overcast, mercifully cool June day. It was four steep miles to the summit at just under 4,000 feet. For a little over a hundred miles through Vermont the AT coexists with the Long Trail, which threads its way up and over the biggest and most famous peaks of the Green Mountains all the way to Canada. The Long Trail is actually older than the AT-it was opened in 1921, the year the AT was proposed-and I’m told that there are Long Trail devotees even yet who look down on the AT as a rather vulgar and overambitious upstart. In any case, Stratton Mountain is usually cited as the spiritual birthplace of both trails, for it was here that James p. Taylor and Benton MacKaye claimed to have received the inspiration that led to the creation of their wilderness ways-Taylor in 1909, MacKaye sometime afterwards.

Stratton was a perfectly fine mountain, with good views across to several other well-known peaks-Equinox, Ascutney, Snow, and Monadnock-but I couldn’t say that it was a summit that would have inspired me to grab a hatchet and start clearing a route to Georgia or Quebec. Perhaps it was just the dull, heavy skies and bleak light, which gave everything a flat, washed-out feel. Eight or nine other people were scattered around the summit, including one youngish, rather pudgy man on his own in a very new and expensive-looking windcheater. He had some kind of handheld electronic device with which he was taking mysterious readings of the sky or landscape.

He noticed me watching and said, in a tone that suggested he was hoping someone would take an interest, “It’s an Enviro Monitor.”

“Oh, yes?” I responded politely.

“Measures eighty values-temperature, UV index, dew point, you name it.” He tilted the screen so I could see it. “That’s heat stress.” It was some meaningless number that ended in two decimal places. “It does solar radiation,” he went on, “barometric pressure, wind chill, rainfall, humidity-ambient and active-even estimated burn time adjusted for skin type.”

“Does it bake cookies?” I asked.

He didn’t like this. “There are times when it could save your life, believe me,” he said, a little stoutly. I tried to imagine a situation in which I might find myself dangerously imperiled by a rising dew point and could not. But I didn’t want to upset the man, so I said: “What’s that?” and pointed at a blinking figure in the upper lefthand corner of the screen.

“Ah, I’m not sure what that is. But this-“he stabbed the console of buttons-“now this is solar radiation.” It was another meaningless figure, to three decimal places. “It’s very low today,” he said, and angled the machine to take another reading. “Yeah, very low today.” Somehow I knew this already. In fact, although I couldn’t attest any of it to three decimal places, I had a pretty good notion of the weather conditions generally, on account of I was out in them. The interesting thing about the man was that he had no pack, and so no waterproofs, and was wearing shorts and sneakers. If the weather did swiftly deteriorate, and in New England it most assuredly can, he would probably die, but at least he had a machine that would tell him when and let him know his final dew point.

I hate all this technology on the trail. Some AT hikers, I had read, now carry laptop computers and modems, so that they can file daily reports to their family and friends. And now increasingly you find people with electronic gizmos like the Enviro Monitor or wearing sensors attached by wires to their pulse points so that they look as if they’ve come to the trail straight from some sleep clinic.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Walk In The Woods» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.