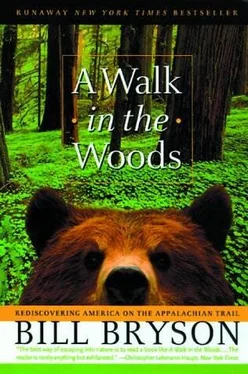

Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Walk In The Woods

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Walk In The Woods: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Walk In The Woods»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Walk In The Woods — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Walk In The Woods», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I didn’t really expect to encounter a mountain lion, but only the day before I had read an article in the Boston Globe about how western mountain lions (which indubitably are not extinct) had recently taken to stalking and killing hikers and joggers in the California woods, and even the odd poor soul standing at a backyard barbecue in an apron and funny hat. It seemed a kind of omen.

It’s not entirely beyond the realm of possibility that mountain lions could have survived undetected in New England. Bobcats-admittedly much smaller creatures than mountain lions-are known to exist in considerable numbers and yet are so shy and furtive that you would never guess their existence. Many forest rangers go whole careers without seeing one. And there is certainly ample room in the eastern woods for large cats to roam undisturbed. Massachusetts alone has 250,000 acres of woodland, 100,000 of it in the comely Berkshires. From where I was now, I could, given the will and a more or less infinite supply of noodles, walk all the way to Cape chidley in northern Quebec, 1,800 miles away on the icy Labrador Sea, and scarcely ever have to leave the cover of trees. Even so, it is unlikely that a large cat could survive in sufficient numbers to breed not just in one area but evidently all over New England and escape notice for nine decades. Still, there was that scat. Whatever it was, it excreted like a mountain lion.

The most plausible explanation was that any lions out there-if lions they were-were released pets, bought in haste and later regretted. It would be just my luck, of course, to be savaged by an animal with a flea collar and a medical history. I imagined lying on my back, being extravagently ravaged, inclining my head slightly to read a dangling silver tag that said: “My name is Mr. Bojangles. If found please call Tanya and Vinny at 924- 4667.”

Like most large animals (and a good many small ones), the eastern mountain lion was wiped out because it was deemed to be a nuisance. Until the 1940s, many eastern states had well-publicized “varmint campaigns,” often run by state conservation departments, that awarded points to hunters for every predatory creature they killed, which was just about every creature there was-hawks, owls, kingfishers, eagles, and virtually any type of large mammal. West Virginia gave an annual college scholarship to the student who killed the most animals; other states freely distributed bounties and other cash rewards. Rationality didn’t often come into it. Pennsylvania one year paid out $90,000 in bounties for the killing of 130,000 owls and hawks to save the state’s farmers a slightly less than whopping $1,875 in estimated livestock losses. (It is not very often, after all, that an owl carries off a cow.)

As late as 1890, New York State paid bounties on 107 mountain lions, but within a decade they were virtually all gone. (The very last wild eastern mountain lion was killed in the Smokies in the 1920s.) The timberwolf and woodland caribou also disappeared from their last Appalachian fastnesses in the first years of this century, and the black bear very nearly followed them. In 1900, the bear population of New Hampshire-now over 3,000-had fallen to just fifty.

There is still quite a lot of life out there, but it is mostly very small. According to a wildlife census by an ecologist at the University of Illinois named V. E. Shelford, a typical ten-square-mile block of eastern American forest holds almost 300,000 mammals-220,000 mice and other small rodents, 63,500 squirrels and chipmunks, 470 deer, 30 foxes, and 5 black bears.

The real loser in the eastern forests has been the songbird. One of the most striking losses was the Carolina parakeet, a lovely, innocuous bird whose numbers in the wild were possibly exceeded only by the unbelievably numerous passenger pigeon. (When the first pilgrims came to America there were an estimated nine billion passenger pigeons-more than twice the number of all birds found in America today.) Both were hunted out of existence-the passenger pigeon for pig feed and the simple joy of blasting volumes of birds from the sky with blind ease, the Carolina parakeet because it ate farmers’ fruit and had a striking plumage that made a lovely ladies’ hat. In 1914, the last surviving members of each species died within weeks of each other in captivity.

A similar unhappy fate awaited the delightful Bachman’s warbler. Always rare, it was said to have one of the loveliest songs of all birds. For years it escaped detection, but in 1939, two birders, operating independently in different places, coincidentally saw a Bachman’s warbler within two days of each other. Both shot the birds (nice work, boys!), and that, it appears, was that for the Bachman’s warbler. But there are almost certainly others that disappeared before anyone much noticed. John James Audubon painted three species of bird-the small-headed flycatcher, the carbonated warbler, and the Blue Mountain warbler-that have not been seen by anyone since. The same is true of Townsend’s bunting, of which there is one stuffed specimen in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

Between the 1940s and 1980s, the populations of migratory songbirds fell by 50 percent in the eastern United States (in large part because of loss of breeding sites and other vital wintering habitats in Latin America) and by some estimates are continuing to fall by 3 percent or so a year. Seventy percent of all eastern bird species have seen population declines since the 1960s.

These days, the woods are a pretty quiet place.

Late in the afternoon, I stepped from the trees onto what appeared to be a disused logging road. In the center of the road stood an older guy with a pack and a curiously bewildered look, as if he had just woken from a trance and found himself unaccountably in this place. He had, I noticed, a haze of blackflies of his own.

“Which way’s the trail go, do you suppose?” he asked me. It was an odd question because the trail clearly and obviously continued on the other side. There was a three-foot gap in the trees directly opposite and, in case there was any possible doubt, a white blaze painted on a stout oak.

I swatted the air before my face for the twelve thousandth time that day and nodded at the opening. “Just there, I’d say.”

“Oh, yes,” he answered. “Of course.”

We set off into the woods together and chatted a little about where we had come from that day, where we were headed, and so on. He was a thru-hiker-the first I had seen this far north-and like me was making for Dalton. He had an odd, puzzled look all the time and regarded the trees in a peculiar way, running his gaze slowly up and down their lengths over and over again, as if he had never seen anything like them before.

“So what’s your name?” I asked him.

“Well, they call me chicken John.”

“chicken John!” chicken John was famous. I was quite excited. Some people on the trail take on an almost mythic status because of their idiosyncrasies. Early in the trip Katz and I kept hearing about kid who had equipment so high-tech that no one had ever seen anything like it. One of his possessions was a self-erecting tent. Apparently, he would carefully open a stuff sack and it would fly out, like joke snakes from a can. He also had a satellite navigation system, and goodness knows what else. The trouble was that his pack weighed about ninety-five pounds. He dropped out before he got to Virginia, so we never did see him. Woodrow Murphy, the walking fat man, had achieved this sort of fame the year before. Mary Ellen would doubtless have attracted a measure of it if she had not dropped out. chicken John had it now-though I couldn’t for the life of me recall why. It had been months before, way back in Georgia, that I had first heard of him.

“So why do they call you chicken John?” I asked.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Walk In The Woods» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.