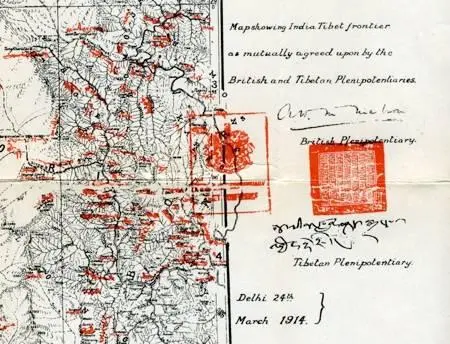

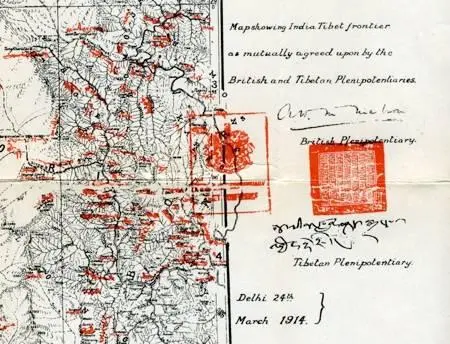

Tibet signed a number of treaties and conventions with Britain culminating in the Simla Treaty of 1914 by which British India and Tibet reached an agreement on their common frontier. [51]India ’s present-day claims to the demarcation of its northern border (the McMahon Line) is based on this treaty which was signed by independent Tibet – not China.

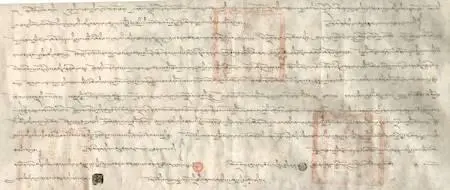

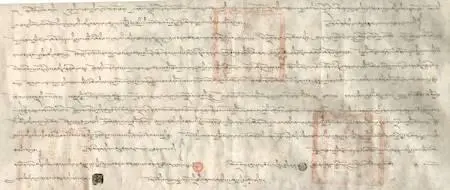

In January 1913, Tibet and Mongolia signed a treaty in Urga, the preamble of which reads: “Whereas Mongolia and Tibet having freed themselves from the Manchu dynasty and separated themselves from China, have become independent states, and whereas the two States have always professed one and the same religion, and to the end that their ancient mutual friendships may be strengthened…” [52]Declarations of friendship, mutual aid, Buddhist fraternity, and mutual trade etc., follow in the various articles. The Tibetan word “rangzen” is used throughout to mean “independence”.

Mongolian Tibet Treaty of 1913

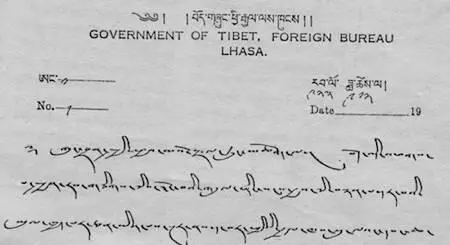

Foreign Bureau personnel

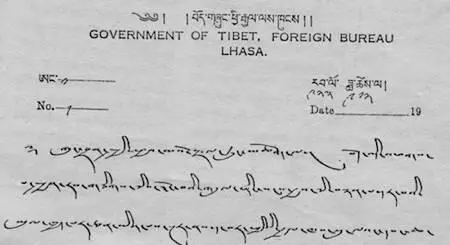

A Bureau of Foreign Affairs was established in 1909 [53]after the 13th Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa from Peking, and the Tibetan people, in symbolic rejection of Manchu rule, presented him with a new national seal. [54]The Foreign Bureau appears to have been reconstituted in 1941. [55]It conducted diplomatic relations with Britain, USA, Nepal, independent India and China. Nepal set up its legation in Lhasa in 1856, China in 1934 and Britain in 1936. Foreign ministry officials represented Tibet as an independent nation in the Inter-Asian Relations Conference convened in India March 23, 1947 to assess the status of Asia in the period following WWII. Tibet was also represented at the Afro-Asian Conference in 1948. Many participating nations were yet to be decolonized making Tibet one of the few established independent nations in that early pan-Asian gathering. [56]

A letter from the Foreign Bureau dated 2nd Nov 1949, to “Mr. Mautsetung”, describes Tibet as a religious nation, independent from “earliest times”, and requests the Communist leader to “issue strict orders” to his officers not to cross into Tibetan territory. Regarding Tibetan territory earlier annexed by China the letter states that “…the Tibetan government would like to open negotiations after the settlement of the Chinese Civil War.” [57]

Foreign Bureau letter to Mao Tsetung

NEUTRALITY IN WORLD WAR II

President Roosevelt’s envoys and gifts (above) to the Dalai Lama

Tibet was a declared neutral country ( bharnas gyalkhap ) during WWII. The Tibetan government successfully resisted pressure from Britain, a threat of invasion from China, and even the personal request of President Roosevelt [58]to allow construction of a military road through Tibetan territory, or allow the passage of military supplies. In a humanitarian gesture, passage of non-military goods was later permitted. Tibet granted political asylum to two Austrian climbers [59]who escaped from a British POW camp in India. It also provided hospitality and transport to American flyers whose plane crashed in Tibet in 1944. [60]

The modern Tibetan postal service was built on courier systems used during the early Tibetan Empire and later Mongol Imperial rule. A “pony express” ( atrung ) service was used for official missives, while general mail was carried by a system of postal-runners ( bhangchen or dakpa ). A Central Post and Telegraph Office ( dak-tar laykhung ) was created in 1920 in Lhasa [61]which took over the old postal stations (tasam) throughout Tibet. Postage stamps of various denominations were indigenously designed and hand-printed, and are now collector’s items. Though not a signatory to the International Postal Treaty, a system was created so that letters from Tibet could be delivered to foreign addresses, [62]and letters from abroad be delivered inside Tibet.

Tibetan postage stamps and envelope with New Jersey address

Spencer Chapman, visiting Lhasa in 1936, declared that, “the postal and telegraph system is most efficient.” [63]The same system continued for some years after 1950. The Czech filmmaker Vladimir Cis (working for the Chinese Communist government) had a letter from his family in Prague delivered to him in the wilderness of Tibet by a postal-runner in 1954. [64]

A telegraph line from India to Lhasa was completed in 1923, along with a basic telephone service. Both were open for public use. The event was commemorated in a publication of the Royal Geographical Society, London. [65]

The Tibetan capital was electrified in 1927. The work of installing both the hydroelectric plant and the distribution system was undertaken near “single-handedly” [66]by a young Tibetan engineer, Ringang. All these projects were initiated and paid for by the Tibetan government.

Radio Lhasa was launched in 1948 and broadcasted news in Tibetan, English and Chinese. [67]

WITNESSES TO INDEPENDENT TIBET

The fact that Tibet was a peaceful, independent country is attested to by the writings of many impartial western observers who not only visited pre-invasion Tibet, but even lived there for considerable periods of time – as the titles of some of their memoirs seem to proudly proclaim: Twenty Years in Tibet by David McDonald [68], Seven Years in Tibet by Heinrich Harrer [69], and even Eight Years in Tibet, the biography of Peter Aufschnieter. [70]

Richardson at a Lhasa garden party

The premier scholar on Tibet, Hugh Richardson, lived for nine years in Tibet, and his many writings [71]reveal a country that was functioning, orderly, peaceful and with a long history of political independence and cultural achievement. He later wrote, “The British government, the only government among Western countries to have had treaty relations with Tibet, sold the Tibetans down the river…” Richardson also acknowledged that he was “profoundly ashamed” [72]at the British government’s refusal to recognize Tibet ’s historically independent status.”

Sir Charles Bell

Another great scholar and diplomat, Charles Bell, regarded as the “architect of Britain ’s Tibet policy,” was convinced that Britain and America ’s refusal to recognize Tibetan independence (but which they sometimes tacitly acknowledged when it was to their advantage) was largely dictated by their desire “to increase their commercial profits in China.” [73]

Читать дальше

![Edzard Ernst - Trick or Treatment. The Undeniable Facts about Alternative Medicine [Electronic book text]](/books/151762/edzard-ernst-trick-or-treatment-the-undeniable-fa-thumb.webp)