You always knew when you were playing one of those because a little Coelacanth symbol would come up on the screen. Coelacanth. Prehistoric deep-sea fish, long supposed extinct until specimens found in mid-twentieth. Present status unknown. Extinctathon was nothing if not informative. It was like some tedious pedant you got trapped beside on the school van, in Jimmy’s view. It wouldn’t shut up.

“Why do you like this so much?” said Jimmy one day, to Crake’s hunched-over back.

“Because I’m good at it,” said Crake. Jimmy suspected him of wanting to make Grandmaster, not because it meant anything but just because it was there.

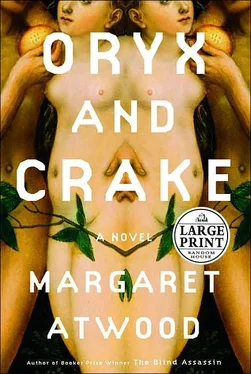

Crake had picked their codenames. Jimmy’s was Thickney, after a defunct Australian double-jointed bird that used to hang around in cemeteries, and—Jimmy suspected—because Crake liked the sound of it as applied to Jimmy. Crake’s codename was Crake, after the Red-necked Crake, another Australian bird—never, said Crake, very numerous. For a while they called each other Crake and Thickney, as an in-joke. After Crake had realized Jimmy was not wholeheartedly participating and they’d stopped playing Extinctathon, Thickney as a name had faded away. But Crake had stuck.

When they weren’t playing games they’d surf the Net—drop in on old favourites, see what was new. They’d watch open-heart surgery in live time, or else the Noodie News, which was good for a few minutes because the people on it tried to pretend there was nothing unusual going on and studiously avoided looking at one another’s jujubes.

Or they’d watch animal snuff sites, Felicia’s Frog Squash and the like, though these quickly grew repetitious: one stomped frog, one cat being torn apart by hand, was much like another. Or they’d watch dirtysockpuppets.com, a current-affairs show about world political leaders. Crake said that with digital genalteration you couldn’t tell whether any of these generals and whatnot existed any more, and if they did, whether they’d actually said what you’d heard. Anyway they were toppled and replaced with such rapidity that it hardly mattered.

Or they might watch hedsoff.com, which played live coverage of executions in Asia. There they could see enemies of the people being topped with swords in someplace that looked like China, while thousands of spectators cheered. Or they could watch alibooboo.com, with various supposed thieves having their hands cut off and adulterers and lipstick-wearers being stoned to death by howling crowds, in dusty enclaves that purported to be in fundamentalist countries in the Middle East. The coverage was usually poor on that site: filming was said to be prohibited, so it was just some desperate pauper with a hidden minivideocam, risking his life for filthy Western currency. You saw mostly the backs and heads of the spectators, so it was like being trapped inside a huge clothes rack unless the guy with the camera got caught, and then there would be a flurry of hands and cloth before the picture went black. Crake said these bloodfests were probably taking place on a back lot somewhere in California, with a bunch of extras rounded up off the streets.

Better than these were the American sites, with their sports-event commentary—“Here he comes now! Yes! It’s Joe ‘The Ratchet Set’ Ricardo, voted tops by you viewers!” Then a rundown of the crimes, with grisly pictures of the victims. These sites would have spot commercials, for things like car batteries and tranquilizers, and logos painted in bright yellow on the background walls. At least the Americans put some style into it, said Crake.

Shortcircuit.com, brainfrizz.com, and deathrowlive.com were the best; they showed electrocutions and lethal injections. Once they’d made real-time coverage legal, the guys being executed had started hamming it up for the cameras. They were mostly guys, with the occasional woman, but Jimmy didn’t like to watch those: a woman being croaked was a solemn, weepy affair, and people tended to stand around with lighted candles and pictures of the kids, or show up with poems they’d written themselves. But the guys could be a riot. You could watch them making faces, giving the guards the finger, cracking jokes, and occasionally breaking free and being chased around the room, trailing restraint straps and shouting foul abuse.

Crake said these incidents were bogus. He said the men were paid to do it, or their families were. The sponsors required them to put on a good show because otherwise people would get bored and turn off. The viewers wanted to see the executions, yes, but after a while these could get monotonous, so one last fighting chance had to be added in, or else an element of surprise. Two to one it was all rehearsed.

Jimmy said this was an awesome theory. Awesome was another old word, like bogus , that he’d dredged out of the DVD archives. “Do you think they’re really being executed?” he said. “A lot of them look like simulations.”

“You never know,” said Crake.

“You never know what?”

“What is reality ?”

“Bogus!”

There was an assisted-suicide site too—nitee-nite.com, it was called—which had a this-was-your-life component: family albums, interviews with relatives, brave parties of friends standing by while the deed was taking place to background organ music. After the sad-eyed doctor had declared that life was extinct, there were taped testimonials from the participants themselves, stating why they’d chosen to depart. The assisted-suicide statistics shot way up after this show got going. There was said to be a long lineup of people willing to pay big bucks for a chance to appear on it and snuff themselves in glory, and lotteries were held to choose the participants.

Crake grinned a lot while watching this site. For some reason he found it hilarious, whereas Jimmy did not. He couldn’t imagine doing such a thing himself, unlike Crake, who said it showed flair to know when you’d had enough. But did Jimmy’s reluctance mean he was a coward, or was it just that the organ music sucked?

These planned departures made him uneasy: they reminded him of Alex the parrot saying I’m going away now . There was too fine a line between Alex the parrot and the assisted suicides and his mother and the note she’d left for him. All three gave notice of their intentions; then all vanished.

Or they would watch At Home With Anna K. Anna K. was a self-styled installation artist with big boobs who’d wired up her apartment so that every moment of her life was sent out live to millions of voyeurs. “This is Anna K., thinking always about my happiness and my unhappiness,” was what you’d get as you joined her. Then you might watch her tweezing her eyebrows, waxing her bikini line, washing her underwear. Sometimes she’d read scenes from old plays out loud, taking all the parts, while sitting on the can with her retro-look bell-bottom jeans around her ankles. This was how Jimmy first encountered Shakespeare—through Anna K.’s rendition of Ma cbeth.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death,

read Anna K. She was a terrible ham, but Snowman has always been grateful to her because she’d been a doorway of sorts. Think what he might not have known if it hadn’t been for her. Think of the words. Sere , for instance. Incarnadine .

“What is this shit?” said Crake. “Channel change!”

“No, wait, wait,” said Jimmy, who had been seized by—what? Something he wanted to hear. And Crake waited, because he did humour Jimmy sometimes.

Or they would watch the Queek Geek Show, which had contests featuring the eating of live animals and birds, timed by stopwatches, with prizes of hard-to-come-by foods. It was amazing what people would do for a couple of lamb chops or a chunk of genuine brie.

Читать дальше