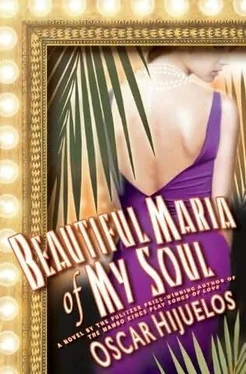

And what did they talk about? It was not as if each was unaware of their parents’ importance to one another: Eugenio had grown up with that song about beautiful María incessantly in his ears, and along the way he had occasionally heard his mother, long since remarried, wistfully lamenting just how much that song, about another woman, had bugged her. But his papi’s death had taken place so long ago that his mother’s anguish seemed overblown to him, in a Cuban manner. (“Oh, she gets hysterical sometimes.”)

“When my best friend wrote that novel and put me in it, as the narrator, I was pissed off,” he said bluntly. “But you know what? I figured he meant well, and what the hell, he brought my papito back to life. But at first, it was rough.” He wiped a fleck of dust from his nose. “And for you?”

“It was very weird. Muy extraño,” she told him. “But, you know, my mother, María, doesn’t seem to mind that she was put in a book, even when she thinks the author got rich.”

He nodded, smiling, and shifted his lanky frame, perhaps feeling that in Teresa he had found a kindred spirit.

AN HOUR LATER, AFTER MARÍA HAD MEANDERED THROUGH THAT apartment, chatting with folks and recognizing, vaguely, as she passed from one hallway into another, Tito Puente, and Ray Barretto, and the American character actor Matt Dillon, a mambo fanatic, holding forth in a cramped vestibule, she plumped down on a leather couch to listen, entirely surrounded by mirrors, to a Cuban-style salon, her face reflecting back at her a hundred times over. With the very dapper and gentlemanly Marco Rizo, Desi Arnaz’s former arranger, sitting before an upright piano playing the melodies of Ernesto Lecuona, Cuba’s Gershwin, if such a comparison can be made, none other than Celia Cruz herself, a most down-to-earth lady, slipped out of the crowd and began to sing, her lovely voice filling the room.

As María felt comfortable, almost to the point of slumber against the couch’s soft leather cushions, she had looked around to see if Eugenio Castillo and her daughter were still conversing. Fortunately-as she hoped-they were, that gallant, his head bowed low as if in reverence to Teresita, whispering tenderly to her and smiling, as if he had stepped out of a dream.

FOR THE RECORD, EUGENIO CASTILLO AND TERESA GARCÍA, HAVING met at that party, maintained contact over the next few years. Now and then, when the telephone rang at around nine thirty at night and María answered, with a melodious “Aquí!” it was that schoolteacher Eugenio Castillo, asking, in his measured voice, if he might speak to her daughter. Every so often, on the weekends, Teresita would feel the sudden compulsion to go off to New York, where that buenmozo’s companionability and, perhaps, his affections awaited her. (“Por Dios, if he’s anything like his papi!”) And María? Oh, she still ached over her memories of that músico from Havana -and for so many other things. It was as if her heart would never allow her mind to forget. But as Nestor Castillo himself, may God preserve his soul, might have put it, even those delicious pains began to slowly fade. For in the course of María’s ordinary days, so unnoticed by the world, she and Luis became as close as any sacrosanct couple, fornicating occasionally, and, in the wake of such intimacy, mostly listening to each other’s verses, which, as it turned out, were nothing more than songs of love.

I would like to thank Will Balliett, my editor at Hyperion, and his colleagues Ellen Archer and Gretchen Young, as well as Jennifer Lyons, Karen Levinson, and Lori Marie Carlson for their invaluable support during the writing of this book.

***

[1] LATER, AFTER SEVERAL HOURS OF SITTING UP DRINKING WITH his brother, and driving him crazy with all his doubts-“Was that canción really any good?” (“Yes, Brother, how many times do I have to tell you!”)-Nestor lay beside his wife, Delores, absently fondling her breasts but thinking about María. If he loved her enough to write that song, why did performing it for the first time in public leave him so low? And why was he filled with such utter misery when, for the first time, he and Cesar finally had a chance at some success? And then he slipped back again into that period of darkness in Havana, when María had thrown him off, and remembered what Cesar had later told him again and again: “Why be stupid about that María when you have such a wonderful woman as Delores in your life?” Ah, but Delores. He’d always told her that “Beautiful María of My Soul” was just a song he’d been fooling with, and there he was, after six years in the States, lying beside Delores and wishing he were back in Havana with María. And he hated himself for that thought, for Delores certainly deserved better. “Te amo, Delores,” he whispered to her again and again. But why was that hole in his heart, like a pin shoved through a photograph from one’s happier youth-as if real happiness was never really possible? Why was he wasting his affections on a woman who had turned into air? He didn’t know, he was just a citified campesino at heart, after all, didn’t know anything about the way real Cuban men treated women. “No soy honesto,” he told himself that night. “No soy decente”-“I’m neither honest or decent.” And he hated himself even more. But thank God that his body, in times of such gloom, always faithfully took over. Kept awake by the clanking of steam pipes, he found himself lifting up the hem of Delores’s nightgown and, feeling the heat of her bottom, drew back her underwear and entered her from behind, Delores, half asleep, sighing at first and then pushing back in a grinding motion and gasping, but not too loudly because she didn’t want the children to hear at the far end of the hall, Nestor, in those same moments, still thinking about María. Then he came after several powerful thrusts, and once he floated back down to earth, he hated himself anew for having that name, that face, that body still lingering stubbornly in his dreams-ah yes, y coño!-María, angel of the heavens, delicious as the balmy dawn off the Malecón and, as women are in many a bolero, an unforgettable apparition of love. [1]

At any rate, that’s basically what happened that night, even as hearsay and the passage of time would embellish that story somewhat differently. According to one of the neighborhood kids, a friend of Nestor’s son, a plump, myopic, and curious fellow who in later years often sat with Cesar Castillo to hear him talk about his glorious dance hall past, that night unfolded differently. Instead of heading straightaway to their hotel on that snowy evening, Desi and his wife decided to visit Nestor’s walk-up apartment on La Salle Street for a midnight meal. Mind you, all those years later, Cesar Castillo was fairly plastered and torn up about all kinds of things in the telling, but even so, with his eyes getting almost teary, he was quite convincing. As Cesar put it, Desi-“a helluva good fellow”-couldn’t have been more gracious, and it wasn’t long before he was sitting in their little kitchen, making himself at home. After savoring a big platter of arroz con pollo and some lemon and garlic and salt-drowned fried tostones, which Delores had prepared in a cloud of sizzling oil and smoke, he strummed Nestor’s guitar and sang a few Cuban songs-“Mama Inéz” and “Guantanamera”-for his new friends. Cesar would swear that Desi himself grew teary eyed over the warmth of their Cuban hospitality and indeed felt perfectly at home, despite the flecking ceiling and hissing steam pipes and half crumpled linoleum floor. Cesar told that story so many times that, in some quarters, it became the official version. In fact, the plump kid went so far as to eventually put it in a book that he would write about the brothers, even if it didn’t get everything right. Whether Desi actually made it there or not, one thing was certain: that wintry night in 1955, the brothers had indeed made Arnaz’s acquaintance at the Mambo Nine club and were promised a chance to appear on his show, where, indeed, as walk-on characters playing Ricky Ricardo’s singing cousins from Cuba, they were to immortalize Nestor’s tormented canción de amor “Beautiful María of My Soul,” a song which his former amante was to hear soon enough on the streets of Havana.