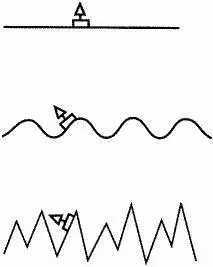

Amadeo Salvatierra, Calle República de Venezuela, near the Palacio de la Inquisición, Mexico City DF, January 1976. What do you mean there's no mystery to it? I said. There's no mystery to it, Amadeo, they said. And then they asked: what does the poem mean to you? Nothing, I said, it doesn't mean a thing. So why do you say it's a poem? Well, because Cesárea said so, I remembered. That's the only reason why, because I had Cesárea's word for it. If that woman had told me that a piece of her shit wrapped in a shopping bag was a poem I would have believed it, I said. How modern, said the Chilean, and then he mentioned someone named Manzoni. Alessandro Manzoni? I asked, remembering a translation of I Promessi Sposi penned by Remigio López Valle, that upstanding gentleman, and published in Mexico in approximately 1930, I'm not sure, Alessandro Manzoni? but they said: Piero Manzoni! the arte povera artist who canned his own shit. Well, what do you know. Art has gone crazy, boys, I said, and they said: it's always been crazy. At that moment I saw something like the shadows of grasshoppers on the walls of the front room, behind the boys and to each side, shadows that slid down from the ceiling and seemed to want to glide across the wallpaper to the kitchen but finally sank into the floor, so I rubbed my eyes and said all right, let's see whether you can explain this poem to me once and for all, because I've been dreaming about it for more than fifty years, give or take a year or two. And the boys rubbed their hands together in sheer excitement, the little angels, and came over to my chair. Let's begin with the title, one of them said. What do you think it means? Zion, Mount Zion in Jerusalem, I said promptly, and also the Swiss city of Sion, Sitten in German, in the canton of Valais. Very good, Amadeo, they said, it's clear you've given it some thought. And which do you choose? Mount Zion, yes? I think so, I said. Obviously, they said. Now let's take the first part of the poem. What do we have? A straight line with a rectangle on it, I said. All right, said the Chilean, forget the rectangle, pretend it doesn't exist. Just look at the straight line. What do you see?

A straight line, I said. What else is there to see, boys? And what does a straight line suggest to you, Amadeo? The horizon, I said. The edge of a table, I said. Peace, said one of them. Yes, peace, calm. All right, then: a horizon and calmness. Now let's look at the second part of the poem:

What do you see, Amadeo? A wavy line, I suppose, what else is there to see? Good, Amadeo, they said, now you see a wavy line. Before, you saw a straight line that made you think of calmness and now you see a wavy line. Does it still suggest calmness to you? I guess not, I said, suddenly seeing what they were getting at, what they wanted me to see. What does the wavy line suggest to you? Hills on the horizon? The sea, waves? Could be, could be. A premonition that the calm will be broken? Movement, change? Hills on the horizon, I said. Maybe waves. Now let's look at the third part of the poem:

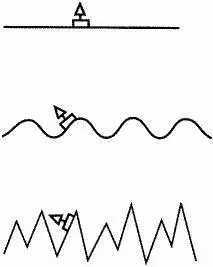

We have a jagged line, Amadeo, which might be many things. Shark's teeth, boys? Mountains on the horizon? The western Sierra Madre? Lots of things, really. And then one of them said: when I was little, I couldn't have been more than six, I would dream about these three lines, the straight line, the wavy line, and the jagged line. I don't know why, but back then I slept under the stairs, or at least in a very low-ceilinged room next to the stairs. It might not have been my house, maybe we were only there for a little while, maybe it was my grandparents' house. And each night, after I'd gone to sleep, the straight line would appear. So far so good. The dream was even pleasant. But little by little the scene would start to change and the straight line would become a wavy line. Then I would start to feel sick and get hotter and hotter and lose my sense of things, my sense of stability, and all I wanted was to go back to the straight line. And yet, nine times out of ten, after the wavy line would come the jagged line, and at that point the best way to describe how I felt was as if I were being torn apart, not from the outside but from the inside, a tearing that began in the belly but that I soon felt in my head and my throat too, and the only way I could escape the pain was by waking up, although waking up wasn't exactly easy. Isn't that strange? I said. Yes, they said, it is strange. It really is strange, I said. Sometimes I would wet my bed, said one of them. Dear, dear, I said. Do you understand now? they said. Well, to be honest, I don't, boys, I said. The poem is a joke, they said, it's easy to see, Amadeo, look: add a sail to each of the rectangles, like this:

What do we have now? A boat? I said. Exactly, Amadeo, a boat. And hidden behind the title, Sión , we have the word navigation . And that's all, Amadeo, it's as simple as that, nothing else to it, said the boys and I would have liked to say that they had taken a weight off my mind, that's what I would have liked to say, or that Sión could also be a front for Simón , a word from the past meaning yes in street slang, but the only thing I did was say well, well, and reach for the bottle of tequila and pour myself a glass, another one. That was all there was left of Cesárea, I thought, a boat on a calm sea, a boat on a choppy sea, and a boat in a storm. For a moment, I can tell you, my head was like a stormy sea and I couldn't hear what the boys were saying, although I did catch some phrases, some stray words, the predictable ones, I suppose: Quetzalcoatl's ship, the nighttime fever of some boy or girl, Captain Ahab's encephalogram or the whale's, the surface of the sea that for sharks is the enormous mouth of hell, the ship without a sail that might also be a coffin, the paradox of the rectangle, the rectangle of consciousness, Einstein's impossible rectangle (in a universe where rectangles are unthinkable), a page by Alfonso Reyes, the desolation of poetry. And then, after I'd drunk my tequila, I filled my cup again and filled theirs, and I said that we should drink to Cesárea, and I saw their eyes, those damn boys were so happy, and the three of us raised our glasses as our little ship was tossed by the gale.

Edith Oster, sitting on a bench in the Alameda, Mexico City DF, May 1990.In Mexico, in Mexico City, I only saw him once, outside the María Morillo gallery, in the Zona Rosa, at eleven in the morning. I had come out onto the sidewalk to smoke a cigarette and he was passing by and stopped to say hello. He crossed the street and said I'm Arturo Belano, Claudia's told me about you. Now I know who you are, I said. I was seventeen then, and I liked to read poetry, but I hadn't read anything by him. He didn't look good, he looked like he'd been up all night, but he was handsome. I mean, he seemed handsome to me then, although I wasn't attracted to him. He wasn't my type. Why is he talking to me? I wondered. Why did he cross the street and stop in front of the gallery? I wondered. There was no one inside and I invited him in, but he said that it was nice outside. The two of us stood there, me with a cigarette in my hand and him just a few feet away in a kind of cloud of dust, looking at me. I don't know what we talked about. I think he asked me to come have coffee at the restaurant next door and I told him I couldn't leave the gallery. He asked me whether I liked my job. It's temporary, I said, I'm quitting next week. Anyway, the pay is really bad. Do you sell a lot of paintings? he said. None yet, I answered, and then we said goodbye and he left. I don't think he was attracted to me, although later he told me that he'd liked me from the first moment he saw me. Back then I was fat or I thought I was fat and I was a nervous wreck. I cried at night and I had an iron will. I was also leading two lives, or a life that was like two lives. On the one hand, I was a philosophy student and I worked temporary jobs like the one at the María Morillo gallery. On the other hand, I was a militant in a Trotskyite party with a clandestine existence that in some confused way I knew served my interests well, although I didn't know what my interests were. One afternoon, when we were handing out leaflets to cars stopped in traffic, I suddenly found myself in front of my mother's Chrysler. Poor thing, the shock almost killed her. And I got so nervous that I handed her the mimeographed sheet and said read this and turned around and left, although as I walked away I heard her say that we would talk at home. We always talked at home. Endless discussions that ended with recommendations, about doctors, movies, books, money, politics.

Читать дальше