Steve Kistulentz - Panorama

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steve Kistulentz - Panorama» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

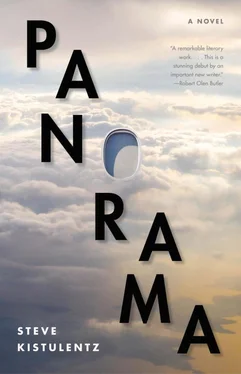

- Название:Panorama

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-316-55177-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Panorama: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Panorama»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Panorama — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Panorama», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Ten hours into the New Year, the airport began to fill with a smattering of travelers all plagued by the rescission of their pledges from the night before, already defaulting on the renouncement of tobacco, the promise of temperance. The bar even offered a midday special, a double for a dollar more. Most travelers would soon abandon the grandiose ambitions of midnight in favor of a more cautious optimism. New Year’s Day meant negotiations, internal debates. One drink wouldn’t hurt.

Shifting in her molded plastic seat, Mary Beth realized she was the loneliest kind of traveler. The worst part of being in an airport was being there alone, with no one to watch your luggage while you darted into an overcrowded and malodorous restroom, no one to laughingly point out the tabloid headlines about your favorite celebrities, no one to share the once-every-two-years pleasure of a box of Good & Plenty. She was flipping through a well-thumbed copy of the USA Today Life section when her eyes caught the image of her brother on the TV, seated in front of a computer-generated backdrop of the Capitol—a short promotional announcement for a scheduled television appearance.

A check of her watch told her she’d be on the way to Dallas by the time he made the air. She wondered when they’d taped the teaser (he’d taught her the whole vocabulary of his strange career) and whether he was going to wear that garish yellow tie before she remembered it was one Gabriel had picked out among the downtrodden orphans that littered the clearance table at Dillard’s; she’d forwarded it along last Christmas, a tentative step toward reconciliation.

Richard made efforts too. A phone call on every occasion he could remember. They had stopped sending Christmas presents to each other years ago, though he managed small, DC-specific presents for his nephew, a Washington Capitals jersey, a T-shirt that said FBI. Sometime in the next few days, Richard would send her a tape of the broadcast, and she would watch him talking about the injustice of the week, sounding the alarm against some unseen evil.

His theatrics made good television. In a thank-you note for the yellow tie, he’d told her that he’d never forgotten a line from a media-studies class in college (she hadn’t known they taught such things in Williamsburg in the early eighties), that television meant appealing to the lowest common denominator; any idiot, Richard said, could understand the theater of the absurd. She wondered if he meant that she was an idiot. She was used to the feeling, just as she was used to being underestimated by the men in her life.

That was certainly his reaction to her pregnancy. “What are you going to do without a husband?” he’d asked, as if thousands of women didn’t raise children without help. Since her husband had gone missing, Richard delved into the literature. He called her with worrisome statistics on preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, mailed photocopied journal articles to her and her obstetrician, flew in for the delivery to feed Mary Beth ice chips, and help her pad slowly up and down the hall. Richard was capable of great gestures. He often forgot her birthday but never Gabriel’s, sending along remembrances with various postmarks, springing sometimes for overnight delivery to ensure they arrived on time: football cards, an extensive set of Legos large enough to build an entire model community, miniature license plates from each state Richard visited. She didn’t have the heart to tell him that the license plates meant more to her than to her son. She looked forward to the videotapes, to his infrequent mail, which came every three months or so; she recognized the arrival of a new plate by the heft of its envelope. She kept them all in her kitchen, used double-sided tape to affix them to the front of her yellowing refrigerator. Seventeen so far.

But this morning Richard MacMurray was not a priority, and she literally shook the thought of her brother out of her head. Now, she needed to figure out where she stood with Mike Renfro.

Why, after all these months of dating, did she still think of him by his first and last names? Even in their most intimate moments, she looked at him and thought Mike Renfro. He had no nickname, no diminutive. Mike had never called her anything more affectionate than MB. And she’d gotten a strong sense all morning, as she watched the city recede behind her into the periphery of the mountainous basin, and again at the curb of the passenger drop-off area in front of terminal 2, and as she waited to board her flight in the order demanded by the gate attendants, how she fell in among competing priorities: she was not at the top of Mike’s, or anyone else’s, list.

In 26C, on the aisle, Mary Beth deposited her carry-on and adjusted herself into the seat, happy that the plane was half-empty—she counted about eighty other intrepid souls. This counting of hers was a hobby, making guestimates of how many people filled the ballroom last night (four hundred) or were waiting in line for a chair on the ski lift Friday morning (eighteen).

With so many empty seats, Mary Beth felt entitled to spread out her magazines and claim the whole row for her comfort. She took out a leather portfolio containing the random fragments of work she had needlessly carried with her on vacation. The portfolio was stamped in gold with the logo of a large company that provided diversified financial services, a broad spectrum of solutions that meant term- and whole-life insurance, retirement plans for individuals and small businesses, long- and short-term disability. Each time Mary Beth looked at the logo or at the bar graphs and pie charts within, the tables of tobacco- and non-tobacco-based premiums, the actuarial predictions of longevity and quality of life, the accidental death and dismemberment plans and their graduated payment schemes— $100,000 for one arm and one leg, or both arms or both legs, $50,000 for one hand and one eye —she was reminded that she made her living as part of the machinery that tampered with the mathematics of death.

Being in this seat, for example, was a bona fide ten-thousand-to-one shot, completely unthinkable. Her son was six years old, and she’d never had a vacation without him until this ridiculous holiday weekend, where a man took her a thousand miles away apparently for the joint purposes of not asking her to marry him, not asking her to help pick out their new house. Whatever his intentions had been, the vacation was now over, and she’d been unable to contrive a way to make him actually say what he wanted. She’d chastise herself later for being so gullible, for letting such mundane fantasies creep into her thinking unrecognized, for craving the regular stability that she wanted for herself and her son, for thinking that anyone other than her would feel responsible enough to want to provide it. She was disappointed at herself for wanting such predictable things, and even more so by the fact that it had taken her so long to realize it. The entire chain of events that had brought her here—all the way back to that Monday morning seven years ago when she learned she was going to be a single mother—was unthinkable. She’d never told Gabriel about how hard she’d tried, in the first years of her marriage, to have a child. Maybe when he was older, she could have a conversation in which she explained the intrusive tests, the blood chemistries that seemed to happen biweekly, the ways she’d tracked her monthly cycle, even the unsympathetic doctor who’d told her that she had an inhospitable womb, a comment he’d apparently forgotten once she’d actually conceived. She’d overcome a recalcitrant husband, fibroids, an obstructed ovary, countless minor issues consigned to the marginalia of her medical records. Which meant that she still labeled her pregnancy a happy accident, the kind of long odds better suited to lottery jackpots and sweepstakes winnings.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Panorama»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Panorama» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Panorama» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.