Finally back on the road again, they had no idea that Philadelphia (which my father was hoping to reach by dawn of the seventeenth) had been occupied by tanks and troops of the U.S. Army, nor did my father know that Uncle Monty, indifferent to my mother's pleading and impervious to any hardship not his own, had fired him for not showing up at work a second week in a row. My father chooses resistance, Rabbi Bengelsdorf chooses collaboration, and Uncle Monty chooses himself.

To get to Boyle County and the Mawhinneys' they had traveled diagonally south across New Jersey to Camden, across the Delaware to Philadelphia, south from there to Baltimore, west and south across the length of West Virginia, and then into Kentucky until, a hundred or so miles on, they reached Lexington and, near a place called Versailles, turned south again for Boyle County's rolling hills. My mother tracked their trip on my encyclopedia's foldout map of the forty-eight states and the ten Canadian provinces, which she spread across the dining room table to look at whenever her anxiety overtook her, while out on the road Sandy, armed with a flashlight for the dark hours, charted their course on an Esso road map and kept an eye out for suspicious-looking characters, especially when they were passing through some grim one-street town whose name he couldn't even find on the map. Excluding the six times that the car broke down on the way back, Sandy counted at least another six in West Virginia when my father-who didn't like the look of a battered truck that was following behind them or of the pickups parked haphazardly by some roadside saloon or of the overalled kid in the gas station who'd pumped their gas and checked the car's front end and then spat on the ground when he took their money-had asked Sandy to open the glove compartment and pass him Mr. Cucuzza's spare pistol to hold in his lap while he drove, and each time sounding as though he, who'd never fired a shot in his life, wouldn't hesitate, if he had to, to pulla the trig'.

Sandy, who once he got home drew from memory his boyhood masterpiece-the illustrated history of their great descent into the hard American world-admitted to having been frightened just about all the time: frightened when they passed through cities where Ku Klux Klansmen had to be lying in wait for any Jew foolhardy enough to be driving through, but no less frightened when they were out beyond the ominous cities, beyond the faded billboards and the tiny filling stations and the last of the shacks where the poorest of people in their threadbare clothes lived-dilapidated timber shacks that Sandy rendered meticulously, underpinned at the four corners by rickety stone piles, with cutout holes for windows and a crudely built chimney crumbling at one end and, on the weather-worn roof, a few scattered rocks holding down the loose shingles-and into what my father called "the wilds." Frightened, said Sandy, speeding past the cows and the horses and the barns and the silos without another car in sight, frightened making hairpin turns up in the mountains without either a shoulder or a guardrail at the side of the road, and frightened when the paved road turned to gravel and the forest closed around them as though they were Lewis and Clark. And especially frightened because our car had no radio, and they didn't know whether the killing of Jews had stopped or whether they might be driving right into the thick of the country's murderous rage against people like us.

Seemingly the sole interlude that hadn't frightened my brother was what had so scared my father out front of the doctor's house: Sandy's drawing a picture of the West Virginia mountain girl whose looks had clearly gotten him all worked up. As it turned out, she'd been exactly the age of "the little factory girl" (as the whole country came to know her) murdered in Atlanta some thirty years earlier by her Jewish supervisor, a married businessman of twenty-nine named Leo Frank. The famous 1913 case of poor Mary Phagan-found dead with a noose around her neck on the floor of the pencil factory basement after going to Frank's office on the day of the murder to collect her pay envelope-had been all over the front pages, North and South, at about the time my father, an impressionable boy of twelve who'd only recently left school to help support the family, was at work in an East Orange hat factory, obtaining a first-class education there in the commonplace libel that linked him inextricably to the crucifiers of Christ. After Frank's conviction (on not entirely reliable circumstantial evidence that is all but discredited today), a fellow prison inmate became a statewide hero by slashing his throat and nearly killing him. One month later, a lynch mob of respectable citizens finished the job by abducting Frank from his jail cell and-much to the satisfaction of my father's co-workers on the factory floor-hanging "the sodomite" from a tree in Marietta, Georgia (Mary Phagan's hometown), as public warning to other "Jewish libertines" to stay the hell out of the South and away from their women.

To be sure, the Frank case was only a part of the history that fed my father's sense of danger in rural West Virginia on the afternoon of October 15, 1942. It all goes further back than that.

This was how Seldon came to live with us. After their safe return to Newark from Kentucky, Sandy moved into the sun parlor and Seldon took over where Alvin and Aunt Evelyn had left off-as the person in the twin bed next to mine shattered by the malicious indignities of Lindbergh's America. There was no stump for me to care for this time. The boy himself was the stump, and until he was taken to live with his mother's married sister in Brooklyn ten months later, I was the prosthesis.

Postscript

Note to the Reader

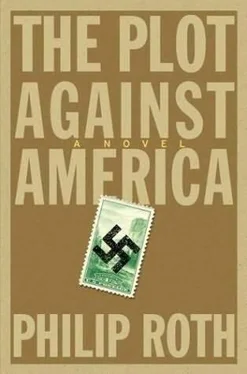

The Plot Against America is a work of fiction. This postscript is intended as a reference for readers interested in tracking where historical fact ends and historical imagining begins. The facts presented below are drawn from the following sources: John Thomas Anderson, Senator Burton K. Wheeler and United States Foreign Relations (dissertation presented to the graduate faculty, University of Virginia), 1982; Neil Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate, 2001; A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, 1998; Biography Resource Center, Newark Evening News and Newark Star-Ledger; Allen Bodner, When Boxing Was a Jewish Sport, 1997; William Bridgwater and Seymour Kurtz, eds., The Columbia Encyclopedia, 1963; James MacGregor Burns, Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom, 1970, and Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox, 1984; Wayne S. Cole, America First: The Battle Against Intervention, 1940-41, 1953; Sander A. Diamond, The Nazi Movement in the United States, 1924-1941, 1974; John Drexel, ed., The Facts on File Encyclopedia of the Twentieth Century, 1991; Henry Ford, The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem, vol. 3, Jewish Influences in American Life, 1920-1922; Neal Gabler, Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of Celebrity, 1994; Gale Group Publishing, Contemporary Authors, vol. 182, 2000; John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, 1999; Susan Hertog, Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life, 1999; Richard Hofstadter and Beatrice K. Hofstadter, eds., Great Issues in American History: From Reconstruction to the Present Day, 1864-1981, vol. 3, 1982; Joseph G. E. Hopkins, ed., Dictionary of American Biography, supplements 3-9, 1974-1994; Joseph K. Howard, "The Decline and Fall of Burton K. Wheeler," Harper's Magazine, March 1947; Harold L. Ickes, The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes, 1939-1941, 1974; Thomas Kessner, Fiorello H. La Guardia and the Making of Modern New York, 1989; Herman Klurfeld, Winchell: His Life and Times, 1976; Anne Morrow Lindbergh, The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith, 1940; Albert S. Lindemann, The Jew Accused: Three Anti-Semitic Affairs (Dreyfus, Beilis, Frank), 1894-1915, 1991; Arthur Mann, La Guardia: A Fighter Against His Times, 1882-1933, 1959; Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager, The Growth of the American Republic, vol. 2, 1962; Charles Moritz, ed., Current Biography Yearbook, 1988, 1988; John Morrison and Catherine Wright Morrison, Mavericks: The Lives and Battles of Montana's Political Legends, 1997; Random House Dictionary of the English Language, 1983; Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Coming of the New Deal, 1933-1935, 1958, and The Politics of Upheaval, 1935-1936, 1960 (vols. 2 and 3 of The Age of Roosevelt ); Peter Teed, A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century History, 1914-1990, 1992; Walter Yust, ed., Britannica Book of the Year Omnibus, 1937-1942, and Britannica Book of the Year, 1943; Ben D. Zevin, ed., Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1932-1945, 1961.

Читать дальше