My brother was known throughout the neighborhood for being able to draw "anything"-a bike, a tree, a dog, a chair, a cartoon character like Li'l Abner-though his interest of late was in real faces. Kids were always gathering around to watch him wherever he would park himself after school with his large spiral pad and his mechanical pencil and begin to sketch the people nearby. Inevitably the onlookers would start to shout, "Draw him, draw her, draw me," and Sandy would take up the exhortation, if only to stop them from screaming in his ear. All the while his hand was working away, he'd look up, down, up, down-and behold, there lived so-and-so on a sheet of paper. What's the trick, they all asked him, how'd you do it, as if tracing-as if outright magic-might have played some part in the feat. Sandy's answer to all this pestering was a shrug or a smile: the trick to doing it was his being the quiet, serious, unostentatious boy that he was. Compelling attention wherever he went by turning out the likenesses people requested had seemingly no effect on the impersonal element at the core of his strength, the inborn modesty that was his toughness and that he later sidestepped at his peril.

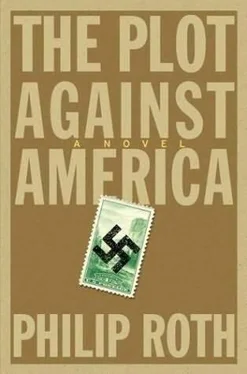

At home, he was no longer copying illustrations from Collier's or photos from Look but studying from an art manual on the figure. He'd won the book in an Arbor Day poster contest for schoolkids that had coincided with a citywide tree-planting program administered by the Department of Parks and Public Property. There'd even been a ceremony where he'd shaken the hand of a Mr. Bann-wart, who was superintendent of the Bureau of Shade Trees. The design of his winning poster was based on a red two-cent stamp in my collection commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of Arbor Day. The stamp seemed to me especially beautiful because visible within each of its narrow, vertical white borders was a slender tree whose branches arched at the top to meet and form an arbor-and until the stamp became mine and I was able to examine through my magnifying glass its distinguishing marks, the meaning of "arbor" had been swallowed up in the familiar name of the holiday. (The small magnifying glass-along with an album for twenty-five hundred stamps, a stamp tweezers, a perforation gauge, gummed stamp hinges, and a black rubber dish called a watermark detector-had been a gift from my parents for my seventh birthday. For an additional ten cents they'd also bought me a small book of ninety-odd pages called The Stamp Collector's Handbook, where, under "How to Start a Stamp Collection," I'd read with fascination this sentence: "Old business files or private correspondence often contain stamps of discontinued issues which are of great value, so if you have any friends living in old houses who have accumulated material of this sort in their attics, try to obtain their old stamped envelopes and wrappers." We didn't have an attic, none of our friends living in flats and apartments had attics, but there'd been attics just beneath the roofs of the one-family houses in Union-from my seat in the back of the car I could see little attic windows at either end of each of the houses as we'd driven around the town on that terrible Saturday the year before, and so all I could think of when we got home in the afternoon were the old stamped envelopes and the embossed stamps on the prepaid newspaper wrappers secreted up in those attics and how I would now have no chance "to obtain" them because I was a Jew.)

The appeal of the Arbor Day commemorative stamp was greatly enhanced by its representing a human activity as opposed to a famous person's portrait or a picture of an important place-an activity, what's more, being performed by children: in the center of the stamp, a boy and a girl looking to be about ten or eleven are planting a young tree, the boy digging with a spade while the girl, supporting the trunk of the tree with one hand, holds it steadily in place over the hole. In Sandy's poster the boy and the girl are repositioned and stand on opposite sides of the tree, the boy is pictured as right-handed rather than left-handed, he wears long pants instead of knickers, and one of his feet is atop the blade pressing it into the ground. There is also a third child in Sandy's poster, a boy about my age, who is now the one wearing the knickers. He stands back and to the side of the sapling and holds ready a watering can-as I held one when I modeled for Sandy, clad in my best school knickers and high socks. Adding this child was my mother's idea, to help distinguish Sandy's artwork from that on the Arbor Day stamp-and protect him from the charge of "copying"-but also to provide the poster with a social content that implied a theme by no means common in 1940, not in poster art or anywhere else either, and that for reasons of "taste" might even have proved unacceptable to the judges.

The third child planting the tree was a Negro, and what encouraged my mother to suggest including him-aside from the desire to instill in her children the civic virtue of tolerance-was another stamp of mine, a brand-new ten-cent issue in the "educators group," five stamps that I'd purchased at the post office for a total of twenty-one cents and paid for over the month of March out of my weekly allowance of a nickel. Above the central portrait, each stamp featured a picture of a lamp that the U.S. Post Office Department identified as the "Lamp of Knowledge" but that I thought of as Aladdin's lamp because of the boy in the Arabian Nights with the magic lamp and the ring and the two genies who give him whatever he asks for. What I would have asked for from a genie were the most coveted of all American stamps: first, the celebrated 1918 twenty-four-cent airmail, a stamp said to be worth $ 3, 400, where the plane pictured at the center, the Army's Flying Jenny, is inverted; and after that, the three famous stamps in the Pan-American Exposition issue of 1901 that had also been mistakenly printed with inverted centers and were worth over a thousand dollars apiece.

On the green one-cent stamp in the educators group, just above the picture of the Lamp of Knowledge, was Horace Mann; on the red two-cent, Mark Hopkins; on the purple three-cent, Charles W. Eliot; on the blue four-cent, Frances E. Willard; on the brown ten-cent was Booker T. Washington, the first Negro to appear on an American stamp. I remember that after placing the Booker T. Washington in my album and showing my mother how it completed the set of five, I had asked her, "Do you think there'll ever be a Jew on a stamp?" and she replied, "Probably-someday, yes. I hope so, anyway." In fact, another twenty-six years had to pass, and it took Einstein to do it.

Sandy saved his weekly allowance of twenty-five cents-and what change he earned shoveling snow and raking leaves and washing the family car-until he had enough to bicycle to the stationery store on Clinton Avenue that carried art supplies and, over a period of months, to buy a charcoal pencil, then sandpaper blocks to sharpen the pencil, then charcoal paper, then the little tubular metal contraption he blew into to apply the fine fixative mist that prevented the charcoal from smudging. He had big bulldog clips, a masonite board, yellow Ticonderoga pencils, erasers, sketchpads, drawing paper-equipment that he stored in a grocery carton at the bottom of our bedroom closet and that my mother, when she was cleaning, wasn't permitted to disturb. His energetic meticulousness (passed on from our mother) and his breathtaking perseverance (passed on from our father) served only to magnify my awe of an older brother who everyone agreed was intended for great things, while most boys his age didn't look as though they were intended even to eat at a table with another human being. I was then the good child, obedient both at home and at school-the willfulness largely inactive and the attack set to go off at a later date-as yet altogether too young to know the potential of a rage of one's own. And nowhere was I less intransigent than with him.

Читать дальше