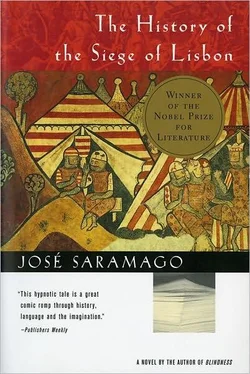

José Saramago - The History of the Siege of Lisbon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «José Saramago - The History of the Siege of Lisbon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The History of the Siege of Lisbon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:9780156006248

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The History of the Siege of Lisbon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The History of the Siege of Lisbon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The History of the Siege of Lisbon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The History of the Siege of Lisbon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Mogueime, too, is in the boat, but alive. He escaped unharmed from the assault, not as much as a scratch, and not because he sheltered from the fighting, on the contrary, one could swear that he was always in the line of fire, handling the battering-rams like Galindo, although the latter was less fortunate. To be sent to the funeral is as good as an official summons, an act of commemoration with the troops on parade, a day off duty, and the sergeant is in no doubt how his men will use their time between going and returning, his great disappointment is not to be able to be part of the retinue, he is going with his captain Mem Ramires to the prince's encampment, where the leaders have been convened to weigh up the outcome, clearly negative, of the assault, which only goes to show that life in the superior ranks is not always a bed of roses, not to mention the more than likely hypothesis that the king would put the blame for this fiasco on his captains, who in their turn would criticise the sergeants, who, poor things, could scarcely excuse themselves by accusing the soldiers of cowardice, for as everyone knows, any soldier owes his worth to his sergeant. If this should happen, there is every chance that permits for burial will be refused, for when all is said and done, these corpses who sail alone have only one route and the time has come to begin the story of the phantom ships. From the hillside opposite, the women at the gates watch the boats approach with their cargo of dead bodies and desires, and any woman who might be indoors with a man will fidget disloyally in order to get rid of him quickly, for the soldiers accompanying these funereal gondolas, perhaps because of an unconscious need to balance the fatality of death with the demands of life, are much more passionate than any soldier or civilian on routine duty, and as we know, generosity always increases in proportion to the satisfaction of ardour. However little a name may be worth, these women, too, have a name, in addition to the collective tide of whore by which they are known, some are called Tareja like the King's mother, or Mafalda, like the queen who came from Savoy last year, or Sancha, or Maiores, or Elvira, or Dórdia, or Enderquina, or Urraca, or Doroteia, or Leonor, and two of them have precious names, one who is called Chamoa, another known as Moninha, enough to make one feel like rescuing them from the streets and taking them home, not out of pity, as Raimundo Silva did with the dog on the Escadinhas de'São Crispim, but in order to try and discover what secret links a person to a name, even when that person scarcely matches up to the name itself.

Mogueime is making this crossing with two declared aims and one that is private. Much has already been said about the declared purpose of the journey, the open trenches are there to receive the dead and the women with open legs to receive the living. His hands still soiled with the dark, moist earth, Mogueime will unfasten his breeches and, pulling up his jacket without taking off any clothes, he will go up to the woman of his choice, she too with her skirt hitched up and bundled round her belly, the art of making love has yet to be invented in these newly-conquered lands, the Moors are said to have taken all their knowledge about love with them, and if any of these prostitutes, being Moorish in origin, has been forced by circumstances to offer her services to foreigners, she will reveal nothing of the amatory skills of her race, until she can begin to sell these novelties at a higher price. Needless to say, the Portuguese are not entirely ignorant in this matter, after all the possibilities depend on means more or less common to all races, but they obviously lack refinement and imagination, have no talent for that subtle gesture or prudent interruption, in a word, are devoid of civilisation and culture. Do not forget that as the hero of this story, Mogueime is more competent and refined than any of his comrades. Lying next to him, Lourenço grunted with pleasure and Elvira screamed, and Mogueime and his whore responded with the same vehemence, Doroteia is determined not to be outdone by Elvira in expansive prodigality, and Mogueime, who is enjoying himself, has no reason to keep quiet. Until the poet Dom Dinis becomes king, let us content ourselves with what we have.

When the boats returned to the other bank, much more swiftly, Mogueime will not return with them. Not because he has decided to desert, any such idea would never have crossed his mind, given his reputation and the fact that his place is already assured in The Grand History of Portugal, these are not things to be thrown away lightly in a reckless moment, after all, this is the same Mogueime who took part in the conquest of Santarém, enough said. His secret objective, which he will not confide even to Galindo, is to go from here, along the routes that were described when the army moved from the Monte de'São Fransisco to the Monte da Graça, as far as the king's encampment, where he knows the crusaders have their separate tents, where he hopes, by some happy coincidence, to find the German's concubine around some corner, she is called Ouroana and she is forever in his thoughts, although he has no illusions that he could ever win her favours, for a soldier without any rank can only aspire to a common prostitute, concubines are reserved for the pleasure of gentlemen, at most swopped around, but always amongst equals. Deep down, he does not believe that he will have the good fortune to see her but how he would love to feel once more that throbbing in the pit of his stomach he has experienced on two occasions, despite everything he has no cause for complaint, for with so many randy men on the prowl, the women are kept under guard, even more so if they go out to get some fresh air, as proved by Ouroana who was always accompanied by one of knight Heinrich's servants, armed as if for battle, although merely a member of the domestic staff.

There are enormous differences between peace and war. When the troops were camped here while the crusaders decided whether they would stay or leave, and there was no warfare apart from the brief skirmish or exchange of arrows and insults, Lisbon looked almost like a jewel resting against the slope and exposed to the voluptuaries of the sun, sparkling all over, and surmounted on high by the mosque of the fortification, resplendent with green and blue mosaics, and, on the slope facing this side, the neighbourhood from where the population had not yet withdrawn, a scene that could only be compared with the ante-chambers of paradise. Now, outside the walls, the houses have been burnt down and the walls demolished, and even from a distance you can see the onslaught of destruction, as if the Portuguese army were a swarm of white ants as capable of gnawing wood as stone, although they might break their teeth and the thread of life in this arduous task, as we have seen, and it will not stop here. Mogueime is not sure if he is afraid of dying. He finds it only natural that others should die, in war this always happens, or is it for this reason that wars are fought, but were he capable of asking himself what he really fears at this time, he would perhaps reply that it is not so much the possibility of meeting his death, who knows, perhaps in the very next assault, but something else which we shall simply call loss, not of life in itself, but of what might happen in life, for example, if Ouroana were to be his the day after tomorrow, unless destiny or Our Lord Jesus Christ should ordain that he must die tomorrow. We know that Mogueime has no such thoughts, he travels by a more straightforward route, whether death comes late or Ouroana comes soon, between the hour of her arrival and the hour of his departure there will be life, but the thought is also much too complicated, so let us resign ourselves to not knowing what Mogueime really thinks, let us turn to the apparent clarity of actions, which are translated thoughts, although in the passage from the latter to the former, certain things are always lost or added, which means that, in the final analysis, we know as little about what we do as about what we think. The sun is high, it will soon be midday, the Moors are certain to be observing any movements in the encampment, watching to see whether the Galicians will stage another attack like that of yesterday when the muezzins summon the faithful to prayer which only goes to show how little respect these heartless creatures have for the religion of others. In order to shorten his journey, Mogueime fords the estuary at the level of the Praça dos Restauradores, taking advantage of the low tide. Soldiers from the detachment assigned to the Porta de Alfofa roam these parts, seeking some distraction from the horrors of battle and trying to catch small fish in the estuary, they have certainly come a long way, and even in those days there was the saying, Out of sight, out of mind, but the allusion here is not to interrupted love affairs, but a question of finding some respite away from the arena of warfare, a sight the more delicate find unbearable once the heat of battle is over. And to avoid any desertions, commanding officers patrol the area, like shepherds or their dogs guarding the flock, there is no other solution, for the soldiers have been paid until August and there is much to be done, day by day, until this period expires, save for any impediment resulting beforehand because another period of expiry has been completed, that of life. Mogueime cannot ford the second branch of the estuary, for it is deeper, even when the tide is out, so he goes up the embankment until he comes to the freshwater streams, where one day he will see Ouroana washing clothes and he will ask her, What is your name, a mere pretext to start up a conversation, for if Mogueime knows anything about this woman, it is her name, he has said it to himself so often that, contrary to appearances, it is not only the days that go on repeating themselves, What is your name Raimundo Silva asked Ouroana, and she replied, Maria Sara.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The History of the Siege of Lisbon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The History of the Siege of Lisbon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The History of the Siege of Lisbon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.