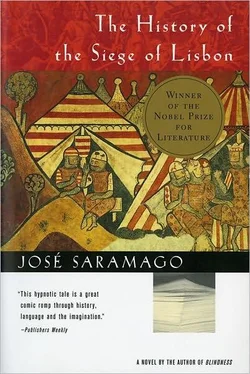

José Saramago - The History of the Siege of Lisbon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «José Saramago - The History of the Siege of Lisbon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The History of the Siege of Lisbon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:9780156006248

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The History of the Siege of Lisbon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The History of the Siege of Lisbon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The History of the Siege of Lisbon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The History of the Siege of Lisbon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This allusion to Moorish dogs, that is to say, the dogs that still lived with the Moors at the time, clearly in their condition as the most impure of animals, but who would soon begin to feed with their foul flesh on the emaciated bodies of the human creatures of Allah, this allusion, as we were saying, reminded Raimundo Silva of the dog on the Escadinhas de'São Crispim, unless, on the other hand, it was an unconscious memory on his part, that led to the introduction of the allegorical picture with that brief commentary about judgment and instinct. As a rule, Raimundo Silva boards the tram at the Portas do Sol, although the distance is greater, and he comes back the same way. If we were to ask him why he does it, he would reply that because he has such a sedentary occupation, it is good for him to walk, but that is not entirely true, the fact is that he would not mind descending the hundred and thirty-four steps, gaining time and benefiting from those sixty-seven flections of each knee, if, out of male pride, he did not also feel obliged to climb up them with the inevitable weariness everyone suffers if they pass this way, as we can see from the small number of mountaineers around. A reasonable compromise would be to go down that way as far as the Porta de Ferro and come back up by the longer but easier route, but to do this would mean acknowledging, all too clearly, that his lungs and legs are no longer what they were, a mere assumption, because the period when Raimundo Silva was in his prime does not come into this history of the siege of Lisbon. On the two or three occasions that he took this route down in recent weeks, Raimundo Silva did not encounter the dog, and thought to himself that, tired of waiting for even the barest ration from the miserly neighbours, the dog had emigrated to richer pastures, or had simply given up the ghost when it could wait no longer. He remembered his act of charity and told himself that he could have done it more often, but when it comes to dogs, you know what it is like, they live with the fixation of acquiring a master, to encourage and feed them is to have them at your feet for evermore, they stare at us with that neurotic anxiety and there is no other solution than to put a collar round their neck, pay for a licence and take them home. The alternative would be to leave them to die of hunger, so slowly that there would be no room for remorse, and, if possible, on the Escadinhas de'São Crispim, where no one ever passes.

News arrived that another burial site had been consecrated on a plain facing the fortress, beneath the slope on the left-hand side of the royal encampment, because of the work involved in transporting corpses across ravines and marshes as far as the Monte de'São Fransisco, who arrived more battered than a load offish and, in this hot weather, smelling worse than the living. As with this new site for burial, the cemetery of'São Vicente is divided into two sections, Portuguese on one side, foreigners on the other, to all appearances a waste of space yet responding, in the final analysis, to that desire for occupation inherent in human nature, and in this sense serving both the living and the dead. When his hour comes, knight Heinrich will end up here, for whom that other hour is at hand when he will prove the tactical excellence of the assault towers, now that direct attacks on gates and walls have met with failure, the first item on the strategic plan. What he does not know, nor could anyone have told him, is that the moment the hopeful eyes of the soldiers are upon him, with the exception of the envious who already existed even then, this very moment, on the threshold of glory, will be that of his unfortunate death, unfortunate in military terms, let's say, because to that other and greater glory, was finally destined he who had come from so far away. But let us not precipitate. The thirty native casualties who lost their lives during the attempted assault on the Porta de Ferro still have to be buried, their corpses will be transported by boat to the other bank of the estuary then carried uphill on improvised litters made from rough pieces of wood. On the edge of the common grave they will be stripped of any clothing that might be used by the living, unless they are much too bloodstained, and even these will be snatched up by the less scrupulous and squeamish, so that generally speaking the dead are lowered into their grave as naked as the earth that receives them.

Lined up, with their bare feet touching the first fringe of mud kept moist and soft by the high tides and waves, the corpses are subjected to the stares and taunts of the victorious Moors up on the battlements, as they he there waiting to be carried on board. There is some delay in transporting them because there are more volunteers than are actually needed, which may seem surprising when the task is so painful and lugubrious, even if we take into account the enticement of being rewarded with clothing, but in fact everyone is trying to get hired as a boatman or drover, because just recently, there alongside the cemetery, prostitutes have gathered from the ravines and outlying districts where they were awaiting the outcome of the war, if it were to be a case of veni, vidi, vici, any precarious arrangement would do, but if it turned out to be a long, drawn-out siege, as looks likely, forcing them to look for greater comfort, they would select some shady spot out of the heat where they might rest from their labours, and set up some wattle huts and use branches to make an awning, for a bed requiring nothing more than an armful of hay or entwined plants which in time will turn to humus and merge with the ashes of the dead. It would not take much learning to observe, as much today as in those medieval times, despite the Church's disapproval of classical similes, how Eros and Thanatos were paired off, in this case with Hermes as intermediary, for it was common practice to use the clothes of the dead to pay for the services of women who, being in the infancy of their art and the nation as yet in its early stages, still accompanied the raptures of their clients with genuine pleasure. Confronted with this, the following discussion will come as no surprise, I'll go, I'll go, which is not a sign of compassion for their lost comrades nor a pretext to escape the contingencies on the front line of battle for a few hours, but rather the insatiable cravings of the flesh, their gratification dependent, would you believe it, on the likes and dislikes on the part of some sergeant-major.

And now let us take a little stroll past this line-up of filthy, bloodstained corpses, lying shoulder to shoulder as they await embarkation, some with their eyes still open and staring heavenwards, others who with half-closed eyelids appear to be suppressing an irresistible urge to burst out laughing, a grim spectacle of festering sores, of gaping wounds devoured by flies, no one knows who these men are or might have been, their names known only to their closest friends, either because they hailed from the same place, or because thrown together as they faced the same dangers, They died for the fatherland, the king would say if he were to come here to pay his last respects, but Dom Afonso Henriques has his own corpses there in his encampment without having to travel all this way, his speech, were he to make it, should be interpreted as that of someone contemplating on equal terms all those who more or less at this hour await despatch, while important matters are being discussed, such as who should be hired as crew or assigned to the cemetery as grave-diggers. The army will not need to inform the relatives of the deceased by telegram, In the fulfilment of his duty, he fell on the field of honour, undoubtedly a much more elegant way of putting it than by simply explaining, His head was smashed in by a heavy stone that some bastard of a Moor threw down from above, the fact is that these armies do not as yet keep a register, the generals, at best, and somewhat vaguely, know that at the outset they had twelve thousand men and that from now on what they must do is to discount so many men each day, a soldier in the front line scarcely needs a name, Listen, simpleton, if you draw back, you'll get a thick ear, and he did not draw back, and the stone came hurtling down and he was killed. He was called Galindo, it's this fellow here, in such a sorry state that even his own mother would not recognise him, his head smashed in on one side, his face covered in congealed blood, and on his right lies Remígio, pierced with arrows, two side by side, because the two Moors who targeted him at the same time had the eye of an eagle and the strength of Samson, but the delay is no disadvantage, their turn will come within the next few days when they too will be exposed to the sun as they await burial inside the city, which being under siege means they cannot get to the cemetery where the Galicians have carried out the most wicked acts of profanation. In their favour, if such a thing can be said, the Moors only have the farewells of their families, the loud lamentations of their womenfolk, but this, who knows, could be even worse for the morale of the soldiers, subjected to a spectacle of tears of sorrow and suffering, of mourning without consolation, My son, my son, while in the Christian encampment only the men are involved, for the women, if there are any, are there for other reasons and purposes, to open their legs for the first man who turns up, whether a soldier be dead or at his post, any differences of length or width are not even noticed after a while, except in exceptional cases. Galindo and Remígio are about to cross the estuary for the last time, if they have ever crossed it before in this sense, for the siege being in the early stages there is no lack of men here who did not get to relieve themselves of secret humours, they entered death full of a life that profited no one. With them, stretched out at the bottom of the boat, one on top of the other, packed tightly because of the confined space, there are also the corpses of Diogo, Gonçalo, Fernão, Martinho, Mendo, Garcia, Lourenço, Pêro, Sancho, Álvaro, Moço, Godinho, Fuas, Arnaldo, Soeiro, and those who still have to be counted, some who have the same name, but not mentioned here so that no one starts complaining, He's been named already, and it would not be true, we might have written, Bernardo is in the boat, when there were thirty corpses with the same name, for we shall never tire of repeating, There is nothing in a name, as proved by Allah himself who despite his ninety-nine names, has only succeeded in being known as God.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The History of the Siege of Lisbon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The History of the Siege of Lisbon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The History of the Siege of Lisbon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.