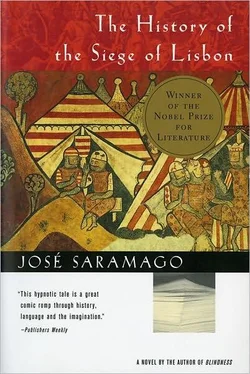

José Saramago - The History of the Siege of Lisbon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «José Saramago - The History of the Siege of Lisbon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The History of the Siege of Lisbon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:9780156006248

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The History of the Siege of Lisbon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The History of the Siege of Lisbon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The History of the Siege of Lisbon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The History of the Siege of Lisbon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Raimundo Silva was favourably impressed by these thoughtful words, not simply because the Moor was leaving it to God to resolve the differences which in his holy name and solely on his behalf bring men to fight each other, but because of the Moor's admirable serenity in the face of possible death, which, being ever certain, becomes fatalistic, as it were, when it comes in the guise of the possible, that sounds like a contradiction but you only have to think about it. Comparing the two speeches, it saddened the proof-reader that a simple Moor deprived of the light of the true faith, even though bearing the tide of governor, should outshine the Archbishop of Braga in prudence and eloquence, despite the prelate's wide experience of codicils, bulls and dogmas. It is only natural that we should prefer to see our own side always gain the upper hand, and Raimundo Silva, although suspicious that there might be more Moorish blood than that of Aryan Lusitanians in the nation to which he belongs, would have liked to applaud Dom João Peculiar's reasoning rather than find himself intellectually outwitted by the exemplary speech of an infidel whose name has been forgotten. However, there is still a possibility that we might finally prevail over the enemy in this rhetorical joust, and that is when the Bishop of Oporto, also armed, begins to speak and, resting his hand on the hilt of his broadsword, he says, We addressed you in friendship, in the hope that our words would fall on friendly ears, but since you have shown annoyance at what we had to say, the time has come for us to speak our mind and tell you how much we despise this habit of yours of waiting for events to take their course and evil to strike, when it is clear for all to see how fragile and weak hope can be, unless you trust in your own valour rather than in the misfortunes of others, it is as if you were already prepared for defeat, only to speak later about the uncertain future, take heed that the more often an enterprise turns out badly, the harder we have to try to make it succeed, and all our efforts against you having been frustrated so far, we are now making another attempt, so that you may finally meet the destiny awaiting you when we enter these gates you refuse to open, yes, live in accordance with God's will, that same will is about to ensure us victory, and there being nothing more to add, we are withdrawing without any further formalities, nor do we expect any from you. Bidding them farewell with these offensive words, the Bishop of Oporto took up the reins of his horse, although in terms of rank, he was not entitled to take this initiative, he had acted out of pique, and was now taking the entire party with him, when the Moor unexpectedly spoke up, without any trace of the intolerable stoicism that had sent the prelate into a rage, now he spoke with the same arrogance and pride, and here is what he had to say, You are making a grave mistake if you confuse patience with cowardice and fear of death, no such mistake was made by your fathers and grandfathers whom we defeated a thousand and one times in armed combat throughout the length and breadth of Spain, and beneath this very soil you tread lie the corpses of those who thought they could challenge our domain, can you not see that your days of conquest are over, your bones will be broken against these walls, your grasping hands cut off, so be prepared to die, for as you well know, we are ever prepared.

There is not a cloud in the sky, the warm sun shines on high, a flock of swallows flies back and forth, circles with much twittering over the heads of these sworn enemies. Mogueime looks up at the sky, gives a shudder, perhaps brought on by the wild screeching of the birds or the Moor's threats, the heat of the sun affords him no comfort, a strange chill makes his teeth chatter, the shame of a man who with a simple ladder brought down Santarém. The silence was broken by the Archbishop of Braga's voice giving an order to the scribe, You must make no mention, Fray Rogeiro, of what the Moor said, words thrown to the wind when we had already departed and were descending the slope of Santo André on our way to the encampment where the king awaits us, he will see, as we draw our swords and raise them to the sunlight, that battle has commenced, and that is something you can certainly write down.

...

DURING THOSE FIRST DAYS after he had thrown away the dyes which for years had concealed the ravages of time, Raimundo Silva, like an ingenuous sower waiting to see the first shoot break through, examined the roots of his hair, day and night, with obsessive interest, morbidly relishing his anticipation of the shock he would almost certainly get once the natural hairs began to appear amongst the dyed ones. But because one's hair, from a certain age onwards, is slow in growing, or because the last dyeing had tinged, or tinted, even the subcutaneous layers, let it be said in passing that all of this is no more than an assumption imposed by the need to explain what is, after all, not very important, Raimundo Silva gradually lost interest in the matter, and now combs his hair without another thought as if he were in the first flush of yiuth, although it is worth noting a certain amount of bad faith in this attitude, a certain falsification of self with oneself, more or less translatable in a phrase that was neither spoken nor thought, Because I can pretend that I cannot see, I do not see, which came to be converted into an apparent conviction, even less clearly expressed, if possible, and irrational, that the last dyeing had been definitive, like some prize conceded by fate in recompense for his courageous renunciation of the world's vanities. Today, however, when he has to deliver to the publisher the novel which he has finally read and prepared for the printers, Raimundo Silva, on entering the bathroom, slowly put his face to the mirror, with cautious fingers he pushed back the tuft of hair on his forehead, and refused to believe what his eyes were seeing, there were the white roots, so white that the contrast in colour seemed to make them whiter still, and they had an unexpected appearance, as if they had sprouted from one day to the next, while the sower had fallen asleep from sheer exhaustion. There and then, Raimundo Silva repented the decision he had taken, that is to say, he did not quite get round to repenting, but thought that he might have postponed it a little longer, he had foolishly chosen the least opportune moment, and he felt so vexed that he wondered whether there might be a bottle which he had forgotten and was still lying around somewhere, with some dye left, at least just for today, tomorrow I'll go back to sticking to my resolution. But he did not start searching, partly because he knew he had thrown out the lot, partly, because he feared, assuming that he found something, that he would have to make another decision, as it was quite possible that he might decide against it and end up playing this game of coming and going for lack of the willpower to refuse to succumb once and for all to the weakness he acknowledges in himself.

When Raimundo Silva wore a wristwatch for the first time many years ago, he was a mere adolescent, and fortune pandered to his immense vanity as he strolled about Lisbon and proudly sported his latest novelty, by crossing his path with that of four different people who were anxious to know the time, Have you the time, they asked, and generous fellow as he was, he did indeed know the time and lost no time in telling them so. The movement of stretching out his arm in order to draw back his sleeve and display the watch's shining face gave him a feeling of importance at that moment that he would never experience again. And least of all now as he makes his way to the publishing house, trying to pass unnoticed in the street or amongst the passengers on the bus, withholding the slightest gesture that might attract the attention of anyone who, also wanting to know the time, might stand there staring in amusement at that unmistakable white line of the parting on the top of his head while waiting for him to overcome his nerves and disentangle his watch from the three sleeves that are covering it today, that of his shirt, his jacket and his coat, It's half past ten, Raimundo Silva finally replies, furious and embarrassed. A hat would come in handy, but that is something the proof-reader has never worn, and if he did, it would only resolve a fraction of his problems, he certainly has no intention of walking into the publishers wearing a hat, Hello there, how is everyone, the hat still stuck on his head as he marches into Dr Maria Sara's office, I've brought you the novel, obviously, it would be best to act as if the colours in his hair were all quite natural, white, black, dyed, people look once, do not look a second time, and by the time they look a third time, they notice nothing. But it is one thing to acknowledge this mentally, to invoke the relativity that conciliates all differences, to ask oneself, with stoic detachment, what a white hair on earth means in the eyes of Venus, another dreadful moment is when he has to confront the telephonist, to withstand her indiscreet glance, to imagine the giggles and whisperings that will while away idle moments in the next few days, Senhor Silva has stopped dyeing his hair, he looks so comical, before they used to mock him because he dyed it, but then there are people who always find something to amuse themselves at the expense of others. And suddenly all these foolish worries disappeared because the telephonist Sara was saying to him, Dr Maria Sara isn't here, she is ill and hasn't come to work for the last two days, these simple words left Raimundo Silva divided between two conflicting sentiments, relief that she should not see his white hair reappearing, and deep distress, not caused by her illness, of the seriousness of which he was still unaware, it could be a flu without complications, or a sudden indisposition, the sort of complaint that affects women, for example, but because he suddenly felt lost, a man risks so much, subjects himself to vexations, just to be able to hand over in person the original manuscript of a novel, and there is no hand there, perhaps it is resting on a pillow beside a pale face, where, until when. Raimundo Silva realises in a second that he has lingered so long in handing over the work in order to savour, with unconscious voluptuousness, the anticipation of a moment that was now eluding him, Dr Maria Sara isn't here, the telephonist had informed him, and he made as if to leave, but then remembered that he ought to entrust the original manuscript to someone, to Costa presumably, Is Senhor Costa here, he asked, suddenly realising that he was deliberately standing in profile to avoid being observed by the telephonist, and, irritated by this show of weakness, he turned around in order to confront all the curiosities of this world, but young Sara did not as much as look at him, she was too busy inserting and pulling out plugs on the old-fashioned switchboard, and all he got was an affirmative gesture as she nodded vaguely towards the inner corridor, all this meaning that Costa was in his office, and that as far as Costa was concerned, there was no need to announce this visitor, something Raimundo Silva did not need to be told because before the arrival of Dr Maria Sara all he had to do was to walk straight in and look for Costa who, as Production Manager, could be found in any of the other offices, pleading, remonstrating, complaining, or simply apologising to the administration, as he always had to do, no matter whether he was responsible or not for any slip-ups in the schedule.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The History of the Siege of Lisbon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The History of the Siege of Lisbon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The History of the Siege of Lisbon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.