“If you don’t have anything for me, forget it,” he said. “Copper, for example. Like yesterday I turned around, and what do you know, this guy unloads a washing-machine motor.”

“Yeah, well, I don’t go in for that,” I said.

I opened the trunk. The food seemed to have doubled in volume. The meat was multicolored, the yogurt was swollen, the cheese was running, and all that was left of the butter was the foil. Generally speaking, everything had fermented, exploded, and oozed-it all formed one rather large compact block, more or less soldered to the carpet on the trunk floor.

I grimaced. The bum’s eyes lit up. It’s always the same story.

“You gonna throw all that away?” he said.

“Yeah,” I said. “I don’t have time to explain. I’m not feeling too hot-I’m unhappy.”

He spit on the ground and scratched his head.

“Hey, we all do what we can,” he said. “Look, fella, you mind if we sort of unload it easy-like? I’d like to take a closer look…”

We each took an end of the carpet and lifted the plaster-like wad out of the trunk. We put it down to one side, at the foot of a garbage-bag wall. Like iron shavings to a magnet, the flies-blue and gold ones-dove into it.

The bum looked at me, smiling. He was obviously waiting for me to split. In his shoes, I’d have done the same thing. I got back in the car without a word. Before taking off I glanced in the rearview mirror. He was still there, standing in the sun next to my small hill of food-he hadn’t moved an inch. He was smiling like he was posing for a souvenir snapshot of one helluva picnic. On the way home I stopped at a bar. I ordered a mint cordial. The oil, the coffee, the sugar, and a big box of chocolate powder those he’d be able to salvage. And the razors with the pivoting heads. And the antimosquito strips. And my box of Fab.

It was about noon when I pulled up in front of the house. The sun was like a hissing cat with its claws out. The telephone was ringing.

“Yes, hello?” I said.

There was static on the other end of the line. I could hardly make out one word.

“Listen, hang up and call back,” I said. “I can’t hear a thing!”

I threw my shoes into a corner. I ran my head under the shower. I lit a cigarette, then the phone rang again.

The guy on the other end said some name and asked me if it was mine.

“Yeah,” I said.

Then he said some other name, and that it was his.

“So…?” I said.

“I have your manuscript in my hands. I’ll send you contracts in the next mail.”

I sat my butt down on the table.

“All right…I want twelve percent,” I said.

“Ten percent.”

“Fine.”

“I loved your book. I’ll have it at the typesetter’s soon.”

“Yeah, do it fast,” I said.

“It’s nice to speak with you, hope to see you soon.”

“Yeah, well, I’m afraid I’ll be pretty tied up for the next little while…”

“Don’t worry about it. No hurry. We’ll take care of the travel arrangements. Things are in the works.”

“Fine.”

“Well, I have to let you go now. Are you working on something else at the moment?”

“Yes, it’s coming along…”

“Terrific. Good luck.”

He was about to hang up-I caught him at the last second.

“Hey… wait… excuse me,” I said. “What did you say your name was, again?”

He repeated it. It was a good thing, too. With all that was happening, it had completely gone out of my head.

I took a pack of sausages out of the refrigerator to thaw. I put some water on. I sat down with a beer. While I was waiting, I laughed louder than I ever had in my life-a nervous laugh.

I got to the hospital early, before visiting hours. I couldn’t figure out if I’d left too early or walked too fast. But one thing was sure-I couldn’t wait to see her. I had brought with me what she’d always wished for. Shouldn’t it be enough to make her jump to her feet? To give me a big wink with the one eye she had left? I made a beeline for the men’s room, as if it were an emergency. From there I surveyed the guy at the reception desk. He seemed to be dozing off. The stairway was empty. I slid by.

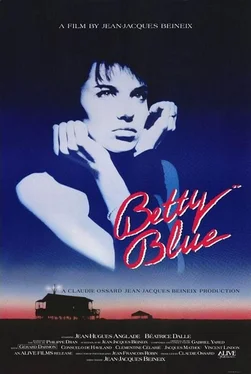

I entered the room. I stumbled forward and grabbed onto the bed railing-I didn’t want to believe what I saw. I shook my head no, hoping that the nightmare would disappear, but it did no good. Betty was lying immobile in bed, staring at the ceiling. She did not move a millimeter, understandably: they had strapped her to the bed-straps at least three inches wide, with aluminum buckles.

“Betty… what’s this all about…?” I whispered.

I still had my Western S.522 on me, the one that fits in any pocket. The curtains were open. A soft light spilled into the room. There was no sound-I sharpened it regularly. Me and my knife, we were pals.

I grabbed Betty by the shoulders. I shook her a little. I started perspiring again, but by now I was used to it-it practically never had a chance to dry. But this was bad sweat, different from the rest-like glazed, transparent blood. I stacked her pillows and sat her up. I found her as beautiful as ever. I had barely let go of her, when she fell over on her side. I picked her back up. When I saw this, a part of me tumbled over the foot of the bed screaming. With the other part, I took her hand.

“Listen,” I said. “I know that it’s taken a long time, but it’s over now-we’ve made it!”

Jerk, I thought, this is no time for riddles. Sure, you’re scared to death, but you have only one little sentence to say-you don’t even have to take a breath.

“Betty… my book is going to be published,” I said.

I might have added: DON’T YOU SEE THE LITTLE WHITE SAIL ON THE HORIZON? I don’t know how to describe this-she might as well have been sealed in a bell jar… and all I could do was leave my fingerprints on the glass. I did not detect the slightest change on her face. A little wind, I was-trying my best to ripple a pond long since covered with ice. A little wind…

“I’m not kidding! And, I’m pleased to announce that I’m working on a new one…!”

I was playing all my cards. The trouble is, I’d never played alone. Lose all night long, then deal yourself a hand in the morning after everyone’s gone home, only to find yourself with a royal flush-who could stand such a thing? Who wouldn’t want to throw everything out the window-stab the upholstery with a kitchen knife?

God, she didn’t see me. She didn’t understand me-didn’t even hear me. She no longer knew what it was to speak, or cry, or smile, or throw a temper tantrum, or revel in the sheets, running her tongue over her lips. The sheets didn’t move. Nothing moved. She gave me no sign, not even a microscopic one. My book being published affected her about as much as my showing up with a plate of french fries. The wonderful bouquet I’d brought was nothing but a shadow of wilted flowers, an odor of dried grass. For a fraction of a second I sensed the infinite space that separated us, and ever since then I tell whoever cares to listen that I died once… at thirty-five years of age, of a summer’s day in a hospital room-and it’s no bluff: I am among those who have heard the Grim Reaper whistling through the air. It chilled me to my fingertips. I experienced a moment of panic, but just then a nurse walked in. I didn’t budge.

She was carrying a tray, with a glass of water and pills of every conceivable color on it. She wasn’t the one I knew. She was fat, with yellow hair. She looked at me, then glanced severely at her watch.

“Excuse me,” she said. “But I don’t believe it’s visiting hours yet…!”

Her attention drifted to Betty. Her old sagging jaw dropped open:

“Mother Mary, who untied her?”

Читать дальше