He went and got a bottle out of the cupboard. He took a long swallow. I didn’t want any. I just stood up and went to the window. I pressed my nose against the pane. I stayed there without moving. He went and got his water basin, and charged into the bathroom. I heard the water running. In the street nothing moved.

By the time he came out, I felt better. I was incapable of stringing two thoughts together, but I could breathe again. I went into the kitchen for a beer-my legs were unstable.

“Bob, take me to the hospital. I can’t drive,” I said.

“It’s not worth it-you won’t be able to see her right away. Wait a while.”

I smashed the end of my beer can into the table. It exploded.

“BOB, DRIVE ME TO THE FUCKING HOSPITAL!”

He sighed. I gave him the keys to the Mercedes, and we went downstairs. Night had fallen.

I gritted my teeth all the way there. Bob talked to me, but I understood nothing. I sat there, leaning slightly forward, my arms folded. She’s alive, I said to myself-she’s alive. Slowly, I felt my jaws relax. I could swallow my saliva again. I woke up as if the car had just rolled over three times.

Going through the hospital doors, I realized why I had felt so strange when we’d come to visit Archie, why I’d felt so oppressed, what it all meant. I nearly blacked out again, nearly fell down flat, the monstrous odor sliding over my face, nearly put my head down, lost my strength. I got hold of myself at the last minute. But it wasn’t me-it was her. I would have walked through walls for her if need be. I could have simply chanted her name like a mantra and, in so doing, passed right through. Once you know that, you can be grateful-you can be proud of having accomplished something. I shivered once, then went into the lobby. Into the planet of the damned.

Bob put his hand on my shoulder.

“Go sit down,” he said. “I’ll go get the scoop. Go ahead, go sit down…”

There was an empty bench close by. I obeyed. If he’d told me to lie down on the floor, I’d have done it. As much as the urge to act set me on fire like a tuft of dried grass, the paralysis ran through my veins like a handful of blue ice cubes. I went from one state to the other, without transition. When I sat down, it was in my cold period-my brain was nothing but a soft, lifeless mass. I leaned my head back against the wall. I waited. I must have been near the kitchen. I smelled leek soup.

“Everything’s all right,” he said. “She’s sleeping.”

“I want to see her.”

“Fine. Everything’s arranged. You just have to fill out a few papers.”

I felt my body start to warm up. I stood up and pushed Bob out of my way. My mind began to function again.

“Yeah, well, all that can wait,” I said. “What room is she in?”

I saw a woman sitting in a glass office, looking in my direction, a stack of forms in her hand. She seemed capable of chasing someone up ten flights of stairs.

“Listen,” Bob sighed. “You have to do this. Why make it difficult? She’s got to sleep now, anyway. You can take five minutes to deal with the papers. Everything’s fine. I tell you. There’s no reason to worry anymore.”

He was right, but there was this fire inside me that wouldn’t stop burning. The woman waved her forms, motioning to me to come over. I suddenly felt surrounded by muscular male nurses, tough and mean. One, in fact, passed in front of me-a shark, forearms hairy and jaw square. I saw that it would do no good to play the human torch; I had to deal with the situation. I went to see what the woman wanted. I’d already capitulated to the Infernal Machine-I didn’t want to get ground up by it, too.

She needed information. I sat down facing her. The whole time we talked, I wondered if she wasn’t really a guy in drag.

“Are you the husband?”

“No,” I said.

“A member of the family?”

“No, I’m everything else.”

She raised her eyebrows. She seemed to think she was the key to the universe-the type who wouldn’t dream of filling out forms haphazardly. She looked at me as if I was vulgar flotsam. I was forced to bow my head, in the hope of saving a few precious seconds.

“I live with her,” I said. “I can probably tell you whatever you want to know.”

She ran her tongue over her lipstick, seemingly satisfied.

“Fine, let’s go on, then. Last name?”

I gave her the name.

“First name?”

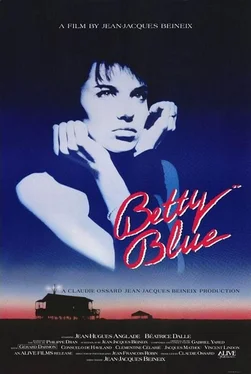

“Betty.”

“Elizabeth?”

“No, Betty.”

“ ‘Betty’ is not a real name.”

I cracked my knuckles as discreetly as possible, leaning forward.

“Then what is it, in your opinion? A new brand of toothpaste?”

I saw her eyes spark. She tortured me for the next ten minutes after that: me helpless in my chair, treading water in her office the longest route to Betty. After a while, I answered her questions with my eyes closed. In the end, I had to promise to come back later with the necessary papers. I’d completely gone south on certain things-numbers of this, and addresses of that, not to mention the things I never knew existed. She sat there twirling her pen between her lips, then came out with: “This woman you live with… you don’t seem to know her very well…”

But Betty, should I have known your blood type? The name of the one-horse town you came from? All your childhood diseases? Your mother’s name? How you react to antibiotics? Was she right? Did I know so little about you? I asked myself this, not caring about the answer; then I stood up and backed out of the room, doubled over from low blows, apologizing for having caused her so much trouble. I even gave her a smile as I closed the door:

“What’s the room number, again?”

“Second floor, room seven.”

Bob was waiting in the lobby. I thanked him for having driven me there, then sent him home with the Mercedes. I told him not to worry, I’d make my own way home. I waited until he was completely out the door, then went to the bathroom to rinse my face. I felt better. I started to get used to the idea that she had torn her eye out. I remembered she had two of them. I became a little meadow under a blue sky-licking my own blades of grass after the rainstorm.

There was a nurse coming out of number seven when I arrived-a blonde with a flat behind and a pleasant smile. She knew who I was right away.

“Everything’s fine. She needs to rest,” she said.

“But I want to see her.”

She stepped aside to let me in. I put my hands in my pockets and looked at the floor. I stopped at the foot of the bed. There was only a small light on. Betty had a wide bandage across her eye. She was sleeping. I looked at her for three seconds, then lowered my eyes. The nurse was standing behind me. Not knowing what else to do, I sniffled. I looked at the ceiling.

“I’d like a minute alone with her,” I said.

“Okay, but no more than that…”

I nodded, without turning around. I heard the door close. There were some flowers on the nightstand. I went over and fiddled with them. Out of the corner of my eye I saw that Betty was breathing-yes, she was, no doubt about it. Though I wasn’t sure it would do any good, I got out my knife and trimmed the stems of the flowers, so they’d live longer. I sat down on the edge of her bed and put my elbows on my knees, my head in my hands. It relaxed my neck. I felt together enough to caress the back of her hand. What a wonder, that hand, what a wonder-I hoped with all my heart that it was the other hand she’d used to do the dirty work. I hadn’t fully digested all that yet.

I stood up and went to look out the window. It was night. Everything seemed to be moving on rollers. You have to recognize that no matter how you look at it, we take turns here on earth: you take the day with the night; the joy with the sorrow, shake it up, and pour yourself a big glass of it every morning. Thus you become a man-nice to have you aboard, son… watch and see how incomparable and sad is the beauty of life.

Читать дальше