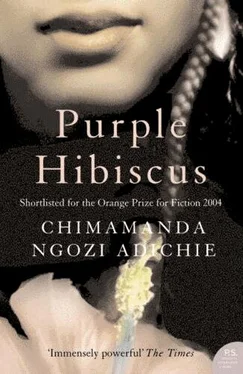

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We are at the prison compound. The bleak walls have unsightly patches of blue-green mold. Jaja is back in his old cell, so crowded that some people have to stand so that others can lie down. Their toilet is one black plastic bag, and they struggle over who will take it out each afternoon, because that person gets to see sunlight for a brief time. Jaja told me once that the men do not always bother to use the bag, especially the angry men. He does not mind sleeping with mice and cockroaches, but he does mind having another man's feces in his face.

He was in a better cell until last month, with books and a mattress all to himself, because our lawyers knew the right people to bribe. But the wardens moved him here after he spat in a guard's face for no reason at all, after they stripped him and flogged him with koboko. Although I do not believe Jaja would do something like that unprovoked, I have no other version of the story because Jaja will not talk to me about it. He did not even show me the welts on his back, the ones the doctor we bribed in told me were puffy and swollen like long sausages. But I see other parts of Jaja, the parts I do not need to be shown, like his shoulders.

Those shoulders that bloomed in Nsukka, that grew wide and capable, have sagged in the thirty-one months that he has been here. Almost three years. If somebody gave birth when Jaja first came here, the child would be talking now, would be in nursery school. Sometimes, I look at him and cry, and he shrugs and tells me that Oladipupo, the chief of his cell-they have a system of hierarchy in the cells-has been awaiting trial for eight years.

Jaja's official status, all this time, has been Awaiting Trial. Amaka used to write the office of the Head of State, even the Nigerian Ambassador in America, to complain about the poor state of Nigeria's justice system. She said nobody acknowledged the letters but still it was important to her that she do something. She does not tell Jaja any of this in her letters to him. I read them-they are chatty and matter-of-fact. They do not mention Papa and they hardly mention prison. In her last letter, she told him how Aokpe had been covered in a secular American magazine; the writer had sounded pessimistic that the Blessed Virgin Mary could be appearing at all, especially in Nigeria: all that corruption and all that heat. Amaka said she had written the magazine to tell them what she thought. I expected no less, of course. She says she understands why Jaja does not write. What will he say?

Aunty Ifeoma doesn't write Jaja, she sends him cassette tape recordings of their voices, instead. Sometimes, he lets me play them on my cassette player when I visit, and other times, he asks me not to. Aunty Ifeoma writes to Mama and me, though. She writes about her two jobs, one at a community college and one at a pharmacy, or drugstore, as they call it.

She writes about the huge tomatoes and the cheap bread. Mostly, though, she writes about things that she misses and things she longs for, as if she ignores the present to dwell on the past and future. Sometimes, her letters go on and on until the ink gets smudgy and I am not always sure what she is talking about. There are people, she once wrote, who think that we cannot rule ourselves because the few times we tried, we failed, as if all the others who rule themselves today got it right the first time. It is like telling a crawling baby who tries to walk, and then falls back on his buttocks, to stay there. As if the adults walking past him did not all crawl, once. Although I was interested in what she wrote, so much that I memorized most of it, I still do not know why she wrote it to me.

Amaka's letters are often quite as long, and she never fails to write, in every single one, how everybody is growing fat, how Chima "outfats" his clothes in a month. Sure, there has never been a power outage and hot water runs from the tap, but we don't laugh anymore, she writes, because we don't have the time to laugh, because we don't even see one another.

Obiora's letters are the cheeriest and the most irregular. He has a scholarship to a private school where, he says, he is praised and not punished for challenging his teachers.

"Let me do it," Celestine says. He has opened the boot, and I am about to bring out the plastic bag of fruits and the cloth bag with the food and plates.

"Thank you," I say, moving aside. Celestine carries the bags and leads the way into the prison building. Mama trails behind. The policeman at the front desk has a toothpick stuck in his mouth. His eyes are jaundiced, so yellow they look dyed. The desk is bare except for a black phone, a fat, tattered logbook, and a pile of watches and handkerchiefs and necklaces crumpled down on one corner.

"How are you, sister?" he says when he sees me, beaming, although his eyes are focused on the bag in Celestine's hand. "Ah! You come with madam today? Good afternoon, madam."

I smile, and Mama nods vacuously. Celestine places the bag of fruit on the counter in front of the guard. Inside is a magazine with an envelope stuffed full of crisp naira notes, fresh from the bank.

The man puts his toothpick down and grabs the bag. It disappears behind the desk. Then he leads Mama and me to an airless room with benches on both sides of a low table. "One hour," he mutters before leaving.

We sit on the same side of the table, not close enough to touch. I know that Jaja will appear soon, and I try to prepare myself. It has not become any easier for me, seeing him here, even after so long. It will be even harder with Mama sitting next to me. It will be hardest because we finally have good news, because the emotions we used to hold back are dissolving and new ones are forming. I take a deep breath and hold it. Jaja will come home soon, Father Amadi wrote in his last letter, which is tucked in my bag. You must believe this. And I believed it, I believed him, even though we had not heard from the lawyers and were not sure. I believe what Father Amadi says; I believe the firm slant of his handwriting. Because he has said it and his word is true.

I always carry his latest letter with me until a new one comes. When I told Amaka that I do this, she teased me in her reply about being lovey-dovey with Father Amadi and then drew a smiling face.

But I don't carry his letters around because of anything lovey-dovey; there is very little lovey-dovey, anyway. He signs off with nothing more than "as always." He never responds with a yes or a no when I ask if he is happy. His answer is that he will go where the Lord sends him. He hardly even writes about his new life, except for brief anecdotes, such as the old German lady who refuses to shake his hand because she does not think a hlack man should be her priest, or the wealthy widow who insists he have dinner with her every night. His letters dwell on me. I carry them around because they are long and detailed, because they remind me of my worthiness, because they tug at my feelings. Some months ago, he wrote that he did not want me to seek the whys, because there are some things that happen for which we can formulate no whys, for which whys simply do not exist and, perhaps, are not necessary. He did not mention Papa-he hardly mentions Papa in his letters-but I knew what he meant, I understood that he was stirring what I was afraid to stir myself. And I carry them with me, also, because they give me grace. Amaka says people love priests because they want to compete with God, they want God as a rival. But we are not rivals, God and I, we are simply sharing. I no longer wonder if I have a right to love Father Amadi; I simply go ahead and love him. I no longer wonder if the checks I have been writing to the Missionary Fathers of the Blessed Way are bribes to God; I just go ahead and write them. I no longer wonder if I chose St. Andrews church in Enugu as my new church because the priest there is a Blessed Way Missionary Father as Father Amadi is; I just go.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)