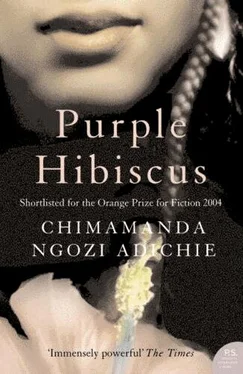

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Aunty Ifeoma looked at me. "What are you waiting for?" she asked, and she raised her wrapper, almost above her knees, and ran after Jaja. I took off, too, feeling the wind rush past my ears.

Running made me think of Father Amadi, made me remember the way his eyes had lingered on my bare legs. I ran past Aunty Ifeoma, past Jaja and Chima, and I got to the top of the hill at about the same time as Amaka.

"Hei!" Amaka said, looking at me. "You should be a sprinter." She flopped down on the grass, breathing hard. I sat next to her and brushed away a tiny spider on my leg.

Aunty Ifeoma had stopped running before she got to the top of the hill. "Nne," she said to me. "I will find you a trainer, eh, there is big money in athletics."

I laughed. It seemed so easy now, laughter. So many things seemed easy now. Jaja was laughing, too, as was Amaka, and we were all sitting on the grass, waiting for Obiora to come up to the top.

He walked up slowly, holding something that turned out to be a grasshopper. "It's so strong," he said. "I can feel the pressure of its wings." He spread his palm and watched the grasshopper fly off. We took our food into the damaged building tucked into the other side of the hill. It may have once been a storeroom, but its roof and doors had been blown off during the civil war years ago, and it had remained that way. It looked ghostly, and I did not want to eat there, although Obiora said people spread mats on the charred floors to have picnics all the time. He was examining the writings on the walls of the building, and he read some of them aloud. "Obinna loves Nnenna forever." "Emeka and Unoma did it here." "One love Chimsimdi and Obi." I was relieved when Aunty Ifeoma said we would eat outside on the grass, since we did not have a mat. As we ate the moi-moi and drank the Ribena, I watched a small car crawl around the base of the hill. I tried to focus, to see who was inside, even though it was too far away. The shape of the head looked very much like Father Amadi's. I ate quickly and wiped my mouth with the back of my hand, smoothed my hair. I didn't want to look untidy when he appeared.

Chima wanted to race down the other side of the hill, the side that didn't have many paths, but Aunty Ifeoma said it was too steep. So he sat down and slithered on his behind down the hill. Aunty Ifeoma called out, "You will use your own hands to wash your shorts, do you hear me?" I knew that, before, she would have scolded him some more and probably made him stop. We all sat and watched him slide down the hill, the brisk wind making our eyes water.

The sun had turned red and was about to fall when Aunty Ifeoma said we had to leave. As we trudged down the hill, I stopped hoping that Father Amadi would appear.

We were all in the living room, playing cards, when the phone rang that evening. "Amaka, please answer it," Aunty Ifeoma said, even though she was closest to the door.

"I can bet it's for you, Mom," Amaka said, focused on her cards. "It's one of those people who want you to dash them our plates and our pots and even the underwear we have on."

Aunty Ifeoma got up laughing and hurried to the phone. The TV was off and we were all silently absorbed in our cards, so I heard Aunty Ifeoma's scream clearly. A short, strangled scream. For a short moment, I prayed that the American embassy had revoked the visa, before I rebuked myself and asked God to disregard my prayers. We all rushed to the room. "Hei, Chi m o! nwunye m! Hei!" Aunty Ifeoma was standing by the table, her free hand placed on her head in the way that people do when they are in shock. What had happened to Mama? She was holding the phone out; I knew she wanted to give it to Jaja, but I was closer and I grasped it. My hand shook so much the earpiece slid away from my ear to my temple.

Mama's low voice floated across the phone line and quickly quelled my shaking hand. "Kambili, it's your father. They called me from the factory, they found him lying dead on his desk."

I pressed the phone tighter to my ear. "Eh?"

"It's your father. They called me from the factory, they found him lying dead on his desk." Mama sounded like a recording. I imagined her saying the same thing to Jaja, in the same exact tone. My ears filled with liquid. Although I had heard her right, heard her say he was found dead on his office desk, I asked, "Did he get a letter bomb? Was it a letter bomb?"

Jaja grabbed the phone. Aunty Ifeoma led me to the bed. I sat down and stared at the bag of rice that leaned against the bedroom wall, and I knew that I would always remember that bag of rice, the brown interweaving of jute, the words adada long GRAIN on it, the way it slumped against the wall, near the table.

I had never considered the possibility that Papa would die, that Papa could die. He was different from Ade Coker, from all the other people they had killed. He had seemed immortal.

I sat with Jaja in our living room, staring at the space where the etagere had been, where the ballet-dancing figurines had been. Mama was upstairs, packing Papa's things. I had gone up to help and saw her kneeling on the plush rug, holding his red pajamas pressed to her face. She did not look up when I came in; she said, "Go, nne, go and stay with Jaja," the silk muffling her voice.

Outside, the rain came down in slants, hitting the closed windows with a furious rhythm. It would hurl down cashews and mangoes from the trees and they would start to rot in the humid earth, giving out that sweet-and-sour scent.

The compound gates were locked. Mama had told Adamu not to open the gates to all the people who wanted to throng in for mgbalu, to commiserate with us. Even members of our umunna who had come from Abba were turned away. Adamu said it was unheard of, to turn sympathizers away. But Mama told him we wished to mourn privately, that they could go to offer Masses for the repose of Papa's soul. I had never heard Mama talk to Adamu that way; I had never even heard Mama talk to Adamu at all.

"Madam said you should drink some Bournvita," Sisi said, coming into the living room. She was carrying a tray that held the same cups Papa had always used to drink his tea. I could smell the thyme and curry that clung to her. Even after she had a bath, she still smelled like that. It was only Sisi who had cried in the household, loud sobs that had quickly quieted in the face of our bewildered silence.

I turned to Jaja after she left and tried speaking with my eyes. But Jaja's eyes were blank, like a window with its shutter drawn across. "Won't you drink some Bournvita?" I asked, finally.

He shook his head. "Not with those cups." He shifted on his seat and added, "I should have taken care of Mama. Look how Obiora balances Aunty Ifeoma's family on his head, and I am older than he is. I should have taken care of Mama."

"God knows best," I said. "God works in mysterious ways." And I thought how Papa would be proud that I had said that, how he would approve of my saying that.

Jaja laughed. It sounded like a series of snorts strung together. "Of course God does. Look what He did to his faithful servant Job, even to His own son. But have you ever wondered why? Why did He have to murder his own son so we would be saved? Why didn't He just go ahead and save us?"

I took off my slippers. The cold marble floor drew the heat from my feet. I wanted to tell Jaja that my eyes tingled with unshed tears, that I still listened for, wanted to hear, Papa's footsteps on the stairs. That there were painfully scattered bits inside me that I could never put back because the places they fit into were gone. Instead, I said, "St. Agnes will be full for Papa's funeral Mass."

Jaja did not respond. The phone started to ring. It rang for a long time; the caller must have dialed a few times before Mama finally answered it.

She came into the living room a short while later. The wrapper casually tied across her chest hung low, exposing the birthmark, a little black bulb, above her left breast. "They did an autopsy," she said. "They have found the poison in your father's body." She sounded as though the poison in Papa's body was something we all had known about, something we had put in there to be found, the way it was done in the books I read where white people hid Easter eggs for their children to find.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)