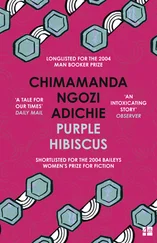

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Poison?" I said.

Mama tightened her wrapper, then went to the windows; she pushed the drapes aside, checking that the louvers were shut to keep the rain from splashing into the house. Her movements were calm and slow. When she spoke, her voice was just as calm and slow. "I started putting the poison in his tea before I came to Nsukka. Sisi got it for me; her uncle is a powerful witch doctor."

For a long, silent moment I could think of nothing. My mind was blank, I was blank. Then I thought of taking sips of Papa's tea, love sips, the scalding liquid that burned his love onto my tongue. "Why did you put it in his tea?" I asked Mama, rising. My voice was loud. I was almost screaming. "Why in his tea?"

But Mama did not answer. Not even when I stood up and shook her until Jaja yanked me away. Not even when Jaja wrapped his arms around me and turned to include her but she moved away.

The policemen came a few hours later. They said they wanted to ask some questions. Somebody at St. Agnes Hospital had contacted them, and they had a copy of the autopsy report with them. Jaja did not wait for their questions; he told them he had used rat poison, that he put it in Papa's tea. They allowed him to change his shirt before they took him away.

Different silence

The Present

The roads to the prison are familiar. I know the houses and shops, I know the faces of the women who sell oranges and bananas just before you turn into the pothole-filled road that leads to the prison yard.

"You want to buy oranges, Kambili?" Celestine asks, slowing the car to a crawl, as the hawkers start to wave and call out to us. His voice is gentle; Mama says it is the reason she hired him after she asked Kevin to leave. That and also that he does not have a dagger-shape scar on his neck.

"What we have in the boot should do," I say. I turn to Mama. "Do you want us to buy anything here?"

Mama shakes her head, and her scarf starts to slip off. She reaches out to knot it again as loosely as before. Her wrapper is just as loose around her waist, and she ties and reties it often, giving her the air of the unkempt women in Ogbete market, who let their wrappers unravel so that everyone sees the hole-riddled slips they have on underneath.

She does not seem to mind that she looks this way; she doesn't even seem to know. She has been different ever since Jaja was locked up, since she went about telling people that she killed Papa, that she put the poison in his tea. She even wrote letters to newspapers. But nobody listened to her; they still don't. They think grief and denial-that her husband is dead and that her son is in prison-have turned her into this vision of a painfully bony body, of skin speckled with blackheads the size of watermelon seeds. Perhaps it is why they forgive her for not wearing all black or all white for a year. Perhaps it is why nobody criticized her for not attending the first- and second-year memorial Masses, for not cutting her hair.

"Try and make your scarf tighter, Mama," I say, reaching out to touch her shoulder.

Mama shrugs, still looking out of the window. "It is tight enough."

Celestine is looking at us in the rearview mirror. His eyes are gentle. He once suggested to me that we take Mama to a dibia in his hometown, a man who is an expert in "these things." I was not sure what Celestine meant by "these things," if he was suggesting that Mama was mad, but I thanked him and told him she would not want to go. He means well, Celestine. I have seen the way he looks at Mama sometimes, the way he helps her get out of the car, and I know he wishes he could make her whole.

Mama and I hardly ever come to the prison together. Usually Celestine takes me a day or two before he takes her, every week. She prefers it, I think. But today is different, special-we have finally been told, for certain, that Jaja will get out. After the Head of State died months ago-they say he died atop a prostitute, foaming at the mouth and jerking-we thought Jaja's release would be immediate, that our lawyers would quickly work something out. Especially with the pro democracy groups demonstrating, calling for a government investigation into Papa's death, insisting that the old regime killed him. But it took a few weeks before the interim civilian government announced that it would release all prisoners of conscience, and weeks more for our lawyers to get Jaja on the list. His name is number four on the list of more than two hundred. He will be out next week.

They told us yesterday, two of our most recent lawyers; both of them have the prestigious SAN, for senior advocate of Nigeria, after their names. They came to our house with the news and with a bottle of champagne tied with a pink ribbon. After they left, Mama and I did not talk about it. We went about carrying, but not sharing, the same new peace, the same hope, concrete for the first time.

There is so much more that Mama and I do not talk about. We do not talk about the huge checks we have written, for bribes to judges and policemen and prison guards. We do not talk about how much money we have, even after half of Papa's estate went to St. Agnes and to the fostering of missions in the church. And we have never talked about finding out that Papa had anonymously donated to the children's hospitals and motherless babies' homes and disabled veterans from the civil war. There is still so much that we do not say with our voices, that we do not turn into words.

"Please put in the Fela tape, Celestine," I say, leaning back on the seat. The brash voice soon fills the car. I turn to see if Mama minds, but she is looking straight ahead at the front seat; I doubt that she can hear anything. Most times, her answers are nods and shakes of the head, and I wonder if she really heard. I used to ask Sisi to talk to her, because she would sit with Sisi in the living room for long hours, but she said Mama would not reply to her, that Mama simply sat and stared. When Sisi got married last year, Mama gave her cartons and cartons of china and Sisi sat on the floor of the kitchen, crying loudly, while Mama watched her.

Sisi comes in now, once in a while, to instruct our new steward, Okon, and to ask if Mama needs anything. Mama usually says nothing, just shakes her head while rocking herself. Last month, when I told her I was going to Nsukka, she did not say anything, either, did not ask me why, though I don't know anybody in Nsukka anymore. She simply nodded.

Celestine drove me, and we arrived around noon, just about when the sun was changing to the searing sun I have long imagined can suck the moisture from bone marrow. Most of the lawns on the university grounds are overgrown now; the long grasses stick up like green arrows. The statue of the preening lion no longer gleams. I asked the new family in Aunty Ifeoma's flat if I could come in, and although they looked at me strangely, they asked me in and offered me a glass of water. It would be warm, they said, because there was no power. The blades of the ceiling fan were encrusted with woolly dust, so I knew there had been no power in a while or the dust would have flown away as the fan turned. I drank all the water, sitting on a sofa with uneven holes at the sides. I gave them the fruits I bought at Ninth Mile and apologized because the heat in the boot had blackened the bananas.

As we drove back to Enugu, I laughed loudly, above Fela's stringent singing. I laughed because Nsukkas untarred roads coat cars with dust in the harmattan and with sticky mud in the rainy season. Because the tarred roads spring potholes like surprise presents and the air smells of hills and history and the sunlight scatters the sand and turns it into gold dust. Because Nsukka could free something deep inside your belly that would rise up to your throat and come out as a freedom song. As laughter. "We are here," Celestine says.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)