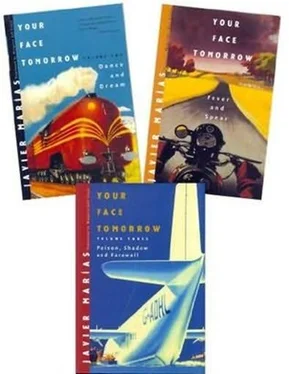

Javier Marias - Your Face Tomorrow 2 - Dance and Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Javier Marias - Your Face Tomorrow 2 - Dance and Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I remember that my father paused at that point or, rather, only afterwards did I realise it was a pause. He had fallen silent, I wondered if he had forgotten what he wanted to talk to me about or tell me, although I doubted that he had, he, too, always used to pick up the thread, or it was enough for me to give the thread a short tug for him to return to the subject. He sat staring straight ahead of him at nothing, his clear, blue eyes gazed back at that time, a time he could doubtless see with absolute clarity, as if he were able to observe it through a pair of supernatural binoculars, it was very like the gaze I had noticed on occasions in Peter Wheeler, or, to be precise, on the occasion when I went up the first flight of his stairs to point out to him and to Mrs Berry where I had found the nocturnal bloodstain that I'd taken so much trouble to expunge and for which neither he nor she had any explanation. It is a gaze one often sees in the old even when they are in company and talking animatedly, the eyes become dull, the iris dilated, staring far, far off, back into the past, as if their owners really could physically see with them, could see their memories I mean. It isn't an absent or a crazed look, but intense and concentrated, focused on something a very long way off. I had noticed it, too, in the bi-coloured eyes of the brother who kept his surname, Toby Rylands. I mean that each of his eyes was of a different colour, his right eye the colour of olive oil and his left that of pale ashes. One keen and almost cruel, the eye of an eagle or a cat, the other the eye of a dog or a horse, meditative and honest. But when they adopted that gaze, his eyes became the same, as if they were, somehow, above mere colour.

'It fell to me to see what went on here in Madrid,' my father continued, 'and I heard more than I saw, much more. I don't know which is worse, hearing an account or actually witnessing what happened. Perhaps, at the time, the latter is less bearable and more horrifying, but it's also easier to erase it or blur it and then deceive yourself about it, convince yourself that you didn't see what you saw, to think that you anticipated with your eyes what you feared might happen and which, in the end, did not. A story, on the other hand, is closed and fixed, and if it has been written down, you can go back and check; and if it's spoken, it can be told to you again, but even if it isn't, words are always less equivocal than actions, at least as regards the words you hear compared with the actions you see. Sometimes actions are only glimpsed, like a flash that lasts no time at all, that dazzles the eyes, and which, afterwards, can be manipulated or cleaned up in your memory, which, however, does not allow such distortion with things heard or told. Of course, it's a bit of an exaggeration to describe as an account what, for example, I happened to overhear one morning on a tram, a few words spoken quite casually, in the weeks after war broke out, weeks of murderous intensity and utter chaos, many people simply gave in to it and were just seething with rage, and if they had any weapons, they did whatever they liked with them and took advantage of the political situation to settle personal scores and wreak the most terrible revenge. Well, you know what it was like, the same in both sectors: in ours, later on, they did at least try to put a stop to all that, but not hard enough; in the other sector, they made almost no attempt at all for the three years the War lasted, nor afterwards either, when the enemy had been defeated. But I was so shocked by the violence described to me – well, not to me, but to anyone within earshot, that's the awful thing- that I can remember precisely where the tram was at that particular moment, the moment when those words reached my ears. We were coming down Alcala and turning into Calle de Velazquez, and a woman sitting in the seat in front of me pointed at a house, at an apartment on one of the top floors, and she said to the woman she was travelling with: "See that house. Some rich people used to live there. We took them out one day and finished off the lot of them. And the little baby they had, I took it out of its cot, grabbed it by its legs, swung it around a few times and smashed its head against the wall. Killed it straight off. We didn't leave a single one of them alive, wiped out the whole damn crew." She was a rather brutish-looking woman, but no more so than many others I'd seen hundreds of times in the market, at church, or in someone's living room, poor and wealthy, shabby and smart, dirty and clean, you get brutes like that everywhere and in every class, I've seen equally brutish women taking communion at midday mass in San Fermin de los Navarros, wearing fur coats and expensive jewellery. The woman talked about the atrocity she'd committed in the same tone as she might have said: "See that house. I worked there for a while, but after a few months I couldn't stand it any longer, so I left, just like that. I walked out on them. That showed them." Perfectly naturally. Without giving it any importance. With the complete sense of impunity that people felt in those days; she didn't care a bit who heard her. She was even rather proud of it, and certainly boastful. And she had nothing but scorn for her victims, of course. And obviously it would have been naive to have expected any remorse from her, even a hint.

I went cold with disgust and got off as soon as I could, one or two stops earlier than I needed to, so as not to have to look at her any more or risk hearing her recount more such exploits. I didn't say anything, you simply couldn't in those days if you wanted to survive, you could be arrested for the slightest thing and bumped off, even if you were a Republican; or like your uncle, Alfonso, who was nothing, just a boy, and the girl who was with him when they picked him up, who was even less than nothing. I glanced at the woman's face as I got off, an ordinary woman, with coarse but not ugly features, quite young, although not young enough to put it all down to the frequent callousness of youth, she might have had children of her own or had them later on. If she survived the War and suffered no reprisals (and she certainly wouldn't have been punished for the thing I heard her describe; although she might have been had she gone on to play a significant part in activities that could be more easily traced and reconstructed at the end of the War or if someone high up took against her and denounced her just like that, or on some intuitive whim; because all those early atrocities were just left in limbo), she probably led a normal existence and never gave much thought to what she had done. She'll be like a lot of women, possibly even cheerful and friendly and nice, with grandchildren she's devoted to, she might even have been a fervent Francoist throughout the dictatorship, and yet none of that will have caused her a flicker of doubt. Many people who were responsible for barbarous acts and crimes against humanity have lived like that quite happily for years; here, and in Germany, in Italy, in France, all of a sudden no one had been a Nazi or a Fascist or a collaborator, everyone had convinced themselves that they hadn't been and would even explain themselves by saying: "No, it wasn't like that for me," that's usually the key phrase. Or else: "Times were different then, you would have to have been there to understand." It is rarely difficult to save yourself from your own conscience if that is what you really want or need to do, still less if that conscience is a shared one, if it's part of a large, collective or even mass conscience, which makes it easier to say: "I wasn't the only one, I wasn't a monster, I was just like everyone else, I wasn't unusual; it was a matter of survival and almost everyone did the same thing, or would have if they'd been born." And people who are religious have it even easier, especially Catholics who have priests to wash clean their sublime regions, their innermost selves, and believe me, the priests here were readier than ever to absolve, to rationalise and to justify whatever vile or cruel deeds their protectors or comrades had committed, bear in mind that they were equally belligerent and egged them on. All that may help, of course, but it isn't even really necessary. People have an incredible capacity willingly to forget the pain they inflicted, to erase their bloody past not just in the eyes of others – their capacity then is infinite, unlimited – but in their own eyes too. To persuade themselves that things were different from the way they actually were, that they did not do what they clearly did do, or that what took place did not take place, and all with their indispensable co-operation. Most of us are past masters at the art of dressing up our own biographies, * or of toning them down, and it's astonishing how easy it is to exile thoughts and bury memories, and to see our sordid or criminal past as a mere dream from whose intense reality we escape as the day progresses, that is, as our life progresses. And yet, on the other hand, after all these years, every time I pass the corner of Alcala and Velazquez, I can't help glancing up at the fourth floor of the building which that woman on the tram, pointed out one morning in 1936, and thinking about that; small, dead child, even though for me the child has no face and no name and even though all I know about him or her are a couple of sinister sentences that chance brought to my ear.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.