Jess Row

Your Face in Mine

For my father

Clark Row

1934–2013

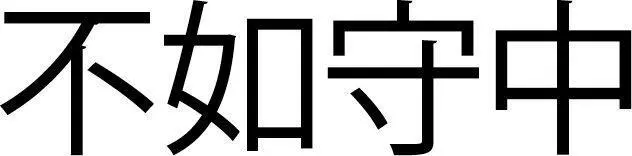

Words are soon exhausted

Hold fast to the center of all things.

— Tao Te Ching, V

And I suggest this: that in order to learn your name, you are going to have to learn mine.

— JAMES BALDWIN

It doesn’t seem possible, even now, that it could begin the way it begins, in the blank light of a Sunday afternoon in February, crossing the parking lot at the Mondawmin Mall on the way to Lee’s Asian Grocery, my jacket in my hand, because it’s warm, the sudden, bleary, half-withheld breath of spring one gets in late winter in Baltimore, and a black man comes from the opposite direction, alone, my age or younger, still bundled in a black lambswool coat with the hood up, and as he draws nearer I feel an unmistakable shock of recognition. Even with the hood, that elected shade, that halo of shadow. I don’t know whether to call it a certain place above the bridge of the nose and between the eyes, or perhaps something about the shape of the nose itself, or the way he carries it. Or the exact way his lips meet. Or the mild inquisitive look in his eyes that changes as I come closer to something unreadable, something close to surprise. I am looking into the face of a black man, and I’ll be utterly honest, unsurprisingly honest: I don’t know so many black men well enough that I would feel such a strong pull, such a decisive certainty. I know this guy, I’m thinking, yet I’m sure I’ve never seen this face before. Who goes around looking for ghost eyes, for pleading looks of remembrance, in the faces of strangers? Not me. He’s coming closer, and I’m running through all my past at a furious clip, riffling frantically the index cards of my memory for a forgotten slight, a stray remark, a door slammed in a black man’s face, a braying car horn behind me on 83 South. He has his eyes trained on me with a faint smile, a smile that dips at the left corner, and says,

Kelly. I’ll bet you’re wondering why I know your name.

I’m sorry, I say. Do I know you?

Kelly, he says, pursing his lips, it’s Martin.

We’re alone, in a field of cracked asphalt, dotted here and there with sprays of tenacious weeds, a mostly abandoned shopping plaza missing its anchor tenant. I would never have come here but for Lee’s being the closest Chinese grocery to my apartment, an emergency stop for days when I unexpectedly run out of tree-ear fungus or Shaoxing wine or shallots or tapioca starch. Yes, we’re in Baltimore; yes, I once lived here, grew up here; but because Baltimore is not just one feeble city but many, and Mondawmin is, to be as honest as I have to be, on the black side of town, in the course of my predictable life, I might as well be on the surface of the moon. As a child I imagined there were hidden places — the tangle of bushes dividing the north and south lanes of the freeway, the fenced-in, overgrown side yard on the far side of our elderly neighbor’s house — that held gaps, portholes, in the fabric of the world, and if I crawled into one of them I would become one of the disappeared children whose faces appeared on circulars and milk cartons and Girl Scout cookie boxes, whose cold bodies were orbiting earth as we spoke, and every so often bumped into the Space Shuttle and slid off, unbeknownst to the astronauts inside. How was I supposed to know that I would only have to cross town to find my own gap, my own way into the beyond?

I cross my arms protectively in front of my chest, and say,

I know you are.

You do?

Martin, I say, I need an explanation.

We cross the parking lot together, Martin, the black man who used to be Martin, ducked slightly behind my right shoulder, flickering in and out of my peripheral vision. Somehow I’m still possessed of enough of my faculties to remember to grab a shopping cart. The sliding door creaks on an unoiled runner, and we breathe in the comforting sting of Asian markets everywhere — dried scallops and mushrooms, wilting choi sum , fish guts in a bucket behind the seafood counter. Mr. Lee looks up at me over yesterday’s Apple Daily —when did they start getting the Hong Kong papers? — and says, you’re too late, the cha siu bao are all sold out.

It’s okay, I say. I need to lose weight anyway.

Yeah, says his daughter, stacking napa cabbages on newspaper in a shopping cart. You’re too fat.

Lee gives her a dour Confucian look. Little number three, he says, that’s enough out of you. And then, turning to me: is the black man with you? He doesn’t speak Chinese, too, does he?

Martin has halted by the soy milk case, reading the labels intently.

Yes, I say. Yes, he’s with me. And no, he doesn’t.

Tell him we don’t have candy bars or potato chips. They always ask.

I give him a noncommittal nod.

My wife was Chinese, I say to Martin, making my way down aisle one, filling the cart with black tree fungus and Sichuan chilies and dried beans and tofu skin. I lived there for three years before I got my Ph.D. She taught me how to cook. My voice sounds bland, conversational, informational: I’ve been stunned, that’s the only way to explain it, stunned back into a certain strained normality. He follows everything I’m saying with lidded eyes and pursed lips, nodding to himself, as if it’s exactly what I would have done, in his mind, as if he could have projected it all, with slight variations.

Hold on. Your wife was ? You’re not together?

No, I say, no, she died. She and my daughter died. In a car accident.

How long?

I look at my watch.

A year, I say, six months, three weeks, and two days.

Mr. Lee, who has never before seen me speaking English, is pretending not to watch us, stealing interested glances over a full-page picture of Maggie Cheung.

I was in Shanghai and Hangzhou once, Martin says. Only briefly, on business. Loved it. Loved the energy. Wish I could have stayed longer.

He reaches up and pulls the hood away from his forehead. His hair, a black man’s hair, of course, razored close to the scalp, with neat lines at the temples and the nape of the neck. The look of a man who’s close friends with his barber. I can’t help thinking of my own scraggling beard, and the last time I tried to crop it into a new shape, how it looked, as Meimei used to put it, half goat-eaten . Fullness of time, I can’t help thinking. The phrase just won’t leave my mind. Fullness of time .

You know, he says. You’re a brave man, Kelly. I think I’d have run away screaming. His voice is different. It is, thoroughly, unmistakably, a black man’s voice, declarative, deep, warm, with a faint twang in the nasal consonants. It’s just a couple of operations, he says. And some skin treatments. In the right hands, no big thing at all. That is to say, it won’t be. When it becomes more common.

Does it, does it — I’m flailing here — does it have a name? What you’ve done?

If it had a name, he says, what would that change, exactly? Would it be more acceptable to you? Would it be a thing people do? Would it have a category unto itself?

Читать дальше