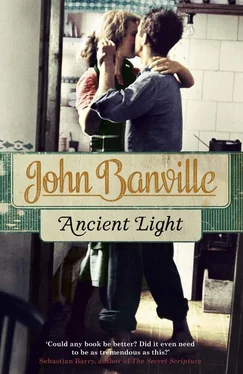

John Banville - Ancient Light

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Banville - Ancient Light» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Viking Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ancient Light

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-670-92061-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Light: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ancient Light»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

gives us a brilliant, profoundly moving new novel about an actor in the twilight of his life and his career: a meditation on love and loss, and on the inscrutable immediacy of the past in our present lives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq-oMYIS44o

Ancient Light — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ancient Light», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Billie, tactful as ever, did not enquire as to why I should be suddenly so eager to trace this woman from my past. It is hard to guess what Billie’s opinion is on any matter. To talk to her is like dropping stones into a deep well; the response that comes back is long-delayed and muted. She has the wariness of a person much put-upon and menaced—that husband again—and before speaking seems to turn over every word carefully and examine it from all sides, testing its potential to displease and provoke. But she must have wondered. I told her Mrs Gray would be old by now or possibly no longer living. I said only that she had been my best friend’s mother and that I had not seen her or heard anything of her for nigh-on half a century. What I did not say, what I emphatically did not say, was why I wished to find her again. And why did I?—why do I? Nostalgia? Whim? Because I am getting old and the past has begun to seem more vivid than the present? No, something more urgent is driving me, though I do not know what it is. I imagine Billie told herself that my age allowed of quixotic self-indulgence, and that if I was prepared to pay her good money to trace some old biddy from my young days she would be a fool herself to question my foolishness. Did she guess my doings with Mrs Gray involved what I had heard her at other times refer to scornfully as hanky-panky? Perhaps she did, and was embarrassed for me, fond old codger that I must appear in her eyes, and that I appear, indeed, in my own. What would she have thought if she knew what thoughts I was thinking about that stricken girl lying in her hospital bed as we spoke? Hanky-panky, indeed.

We walked on. Moorhens now, a hissing stand of reeds, and still those little gold clouds.

Our daughter’s death was made so much the worse for her mother and me by being, to us, a mystery, complete and sealed; to us, though not, I hope, to her. I do not say we were surprised. How could we have been surprised, given the chaotic state of Cass’s inner life? In the months before she died, when she was abroad, an image of her had been appearing to me, a sort of ghost-in-waiting, in daytime dreams that were not dreams. You knew what she was going to do! Lydia had cried at me when Cass was dead. You knew and never said! Did I know, and should I have been able to foresee what she intended, haunted by her living presence as I was? Was it that, in those ghostly visitations, she was sending me somehow a warning signal from the future? Was Lydia right, could I have done something to save her? These questions prey upon me, yet I fear not as heavily as surely they should; ten years of unrelenting interrogation would wear down even the stubbornest devotee of an absconded spirit. And I am tired, so tired.

What was I saying?

Cass’s presence in Liguria

Cass’s presence in Liguria was the first link in the mysterious chain that dragged her to her death on those bleak rocks at Portovenere. What or who was in Liguria for her? In search of an answer, a clue to an answer, I used to pore for hours over her papers, creased and blotted wads of foolscap sheets scratched all over in her minuscule hand—I have them somewhere still—that she left behind her in the room in that foul little hotel in Portovenere that I shall never forget, at the top of the cobbled street from where we could see the ugly tower of the church of San Pietro, the very height she had flung herself from. I wanted to believe that what looked like the frantic scribblings of a mind at its last extremity were really an elaborately encoded message meant for me, and for me alone. And there were places indeed where she seemed to be addressing me directly. In the end, however, wish as I might, I had to accept that it was not me she was speaking to but someone other, my surrogate, perhaps, shadowy and elusive. For there was another presence detectable in those pages, or better say a palpable absence, the shade of a shade, whom she addressed only and always under the name of Svidrigailov.

Flung herself. Why do I say she flung herself from that place? Perhaps she let herself drop as lightly as a feather. Perhaps she seemed to herself to be drifting down to death.

‘She was pregnant, my daughter, when she died,’ I said.

Billie took this without comment, and only frowned, protruding a pink and shiny lower lip. These frowns of hers give her the look of a vexed cherub.

The sky was fading and a chilly dusk was coming on, and I suggested we should stop at a pub to have a drink. This was unusual, for me—I could not remember the last time I had been inside a public house. We went to a place on a corner by one of the canal bridges. Brown walls, stained carpet, a huge television set above the bar with the sound turned down and sportsmen in garish jerseys sprinting and shoving and signalling in relentless dumbshow. There were the usual afternoon men with their pints and racing papers, two or three spivvish young fellows in suits, and the inevitable pair of gaffers sitting opposite each other at a tiny table, smeared whiskey glasses at hand, and sunk in an immemorial silence. Billie looked about with sour disdain. She has a certain hauteur, I have noticed it before. She is, I think, something of a puritan, and secretly considers herself a cut above the rest of us, an undercover agent who knows all our secrets and is privy to our tawdriest sins. She has been a researcher for too long. Her tipple, it turned out, is a splash of gin drowned in a big glass of orange crush and further neutralised by a hefty shovelful of groaning ice cubes. I began to tell her, nursing a thimbleful of tepid port, which I am sure she thought a sissy’s drink, how Billy Gray and I in time discovered that we preferred gin to his father’s whiskey. It was as well, since the bottle we had been winkling out of the cocktail cabinet had over the weeks become so watered down that the whiskey was almost colourless. Gin, quicksilver and demure, now seemed to us altogether more sophisticated and dangerous than whiskey’s rough gold. In the immediate aftermath of my first frolic in the laundry room with Mrs Gray I had been in deep dread of encountering Billy, thinking he was the one, more than my mother, more than his sister, even, who would detect straight off the scarlet sign of guilt that must be blazoned on my brow. But of course he noticed nothing. Yet when he came and leaned down to pour another inch of gin into my glass and I saw the pale patch on the crown of his head the size of a sixpence where his hair whorled, a sense of uncanniness swept over me so that I almost shivered, and I shrank back from him, and held my breath for fear of catching his smell and recognising in it a trace of his mother’s. I tried not to look into the brown depths of those eyes, or dwell on those unnervingly moist pink lips. I felt that suddenly I did not know him, or, worse, that through knowing his mother, in all senses of the word, ancient and modern, I knew him also and all too intimately. So I sat there on his sofa in front of the flickering telly and gulped my gin and squirmed in secret and exquisite shame.

I told Billie Stryker that I would be going away for a time. To this also she offered no response. She really is an incommunicative young woman. Is there something I am missing? There usually is. I said that when I went I would be taking Dawn Devonport with me. I said I was counting on her to break the news of this to Toby Taggart. Neither of his leads would be available for work for a week, at least. At this, Billie smiled. She likes a bit of trouble, does Billie, a bit of strife. I imagine it makes her feel less isolated in her own domestic disorders. She asked where it was I was going. Italy, I told her. Ah, Italy, she said, as if it were her second home.

A trip to Italy, as it happens, was prominent on the list of things that Mrs Gray had longed for and felt she should have by right. Her dream was to set out from one of those fancy Riviera towns, Nice or Cannes or somesuch, and motor along the coast all the way down to Rome to see the Vatican, and have an audience with the Pope, and sit on the Spanish Steps, and throw coins in the Trevi Fountain. She also desired a mink coat to wear to Mass on Sundays, a smart new car to replace the battered old station wagon—‘that jalopy!’—and a red-brick house with a bay window on the Avenue de Picardy in the posher end of town. Her social ambitions were high. She wished her husband were something more than a lowly optician—he had wanted to be a proper doctor but his family had been unable, or unwilling, to pay the college fees—and she was determined that Billy and his sister would do well . Doing well was her aim in everything, giving the neighbours one in the eye, making the town—‘this dump!’—sit up and take notice. She liked to daydream aloud, as we lay in each other’s arms on the floor of our tumbledown love nest in the woods. What an imagination she had! And while she was elaborating these fantasies of bowling along that azure coast in an open sports car swathed in furs with her husband the famous brain surgeon at her side, I would divert myself by pinching her breasts to make the nipples go fat and hard—and these, mark you, were the paps that had given my friend Billy suck!—or running my lips along that pinkly inflamed, serrated track the elastic of her half-slip had imprinted on her tender tummy. She dreamed of a life of romance, and what she got was me, a boy with blackheads and bad teeth and, as she often laughingly lamented, only one thing on his mind.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ancient Light»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ancient Light» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ancient Light» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.