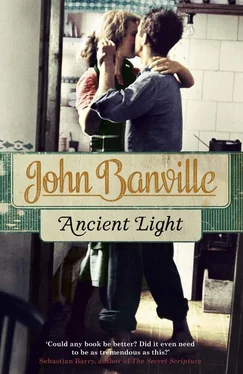

John Banville - Ancient Light

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Banville - Ancient Light» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Viking Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ancient Light

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-670-92061-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Light: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ancient Light»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

gives us a brilliant, profoundly moving new novel about an actor in the twilight of his life and his career: a meditation on love and loss, and on the inscrutable immediacy of the past in our present lives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq-oMYIS44o

Ancient Light — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ancient Light», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And she was, for me, unique. I did not know where in the human scale to place her. Not really a woman, like my mother, and certainly not like the girls of my acquaintance, she was, as I think I have already said, of a gender all to herself. At the same time, of course, she was womanhood in its essence, the very standard by which, consciously or otherwise, I measured all the women who came after her in my life; all, that is, save one. And what would Cass have made of her? How would it have been if Mrs Gray and not Lydia had been my daughter’s mother? The question fills me with alarm and consternation yet since it is posed I must entertain it. Remarkable how the idlest piece of speculation can seem to invert everything in and for an instant. It is as if the world had turned around somehow in a half-circle and shown itself to me from an unfamiliar angle, and I am plunged at once into what feels like happy grief. My two lost loves—is that why I—? Oh, Cass—

That was Billie Stryker just now calling on the telephone, telling me Dawn Devonport tried to kill herself. And failed, it seems.

Part II

___

When my daughter was a little girl she suffered from insomnia, especially in the weeks around midsummer, and sometimes, in desperation, mine and hers, late in those white nights I would bundle her in a blanket into the car and take her for drives northwards along the back roads by the coast, for we were still living by the sea then. She enjoyed these jaunts; even if they did not make her sleep they induced in her a drowsy calm; she said it felt funny to be in the car in her pyjamas, as if she were asleep after all and travelling in a dream. Years later, when she was a young woman, she and I spent a Sunday afternoon retracing our old route up that coastline. We did not acknowledge to each other the sentimental implications of the journey, and I made no mention of the past—one had to be careful of what one said to Cass—but when we got out on that winding road I think she no less than I was remembering those nocturnal drives and the dreamlike sensation of gliding through the greyish darkness, with the dunes beside us and the sea beyond them a line of shining mercury under a horizon so high it seemed it must be a mirage.

There is a place, quite far north, I do not know what it is called, where the road narrows and runs for some way beside cliffs. They are not very high cliffs, but they are high enough and sheer enough to be dangerous, and there are yellow warning notices at intervals all the way along. That Sunday, Cass made me stop the car and get out and walk with her on the clifftop. I was unwilling, having always been afraid of heights, but it would not have done to refuse my daughter so simple a request. It was late spring, or early summer, and the day was brilliant under a scoured sky, with a warm blast of wind coming in off the sea and the sting of iodine in the salt-laden air. I took scant interest in the sparkling scene, however. The look of the swaying waters far below and of the waves gnashing at the rocks was making me nauseous, though I kept up as brave a front as I could manage. Sea birds at eye-level and no more than a few yards away from us hung almost motionless on the updraughts, their wings trembling, their screeches sounding like derisive taunts. After some way the narrow path grew narrower still and made an abrupt descent. Now there was a steep bank of clay and loose stones on one side and nothing on the other save sky and the growling sea. I felt giddier than ever, and went along in a dreadful funk, leaning in towards the bank on my left and away from the windy blue abyss to the right. We should have gone in file, the way was so narrow and the going so treacherous, but Cass insisted on walking beside me, on the very edge of the path, with her arm locked in mine. I marvelled at her lack of fear, and was even starting to feel resentful of her insouciance, for by now my own fright was such that I was sweating and I had begun to tremble. Gradually it became apparent, however, that Cass too was terrified, perhaps more terrified than I was, hearing the wooing wind crooning to her and feeling the emptiness plucking at her coat and the long fall that was only the tiniest sidestep away opening its arms to her so invitingly. She was a lifelong dabbler in death, was my Cass—no, she was more, she was a connoisseur. Striding along that cliff-edge was for her, I am sure, a sip of the deepest, most darksome, brew, the richest vintage. As she held on tight to my arm I could feel the fear thrumming in her, the thrill of terror twitching along her nerves, and I realised that, perhaps because of her fear, I was no longer afraid, and so we went on briskly, father and daughter, and which of the two of us was sustaining the other it was impossible to say.

If she had jumped that day, would she have taken me with her? That would have been a thing, the pair of us plummeting down, feet first, arm in arm, through the bright, blue air.

The private hospital to which they rushed the comatose Dawn Devonport—by helicopter, no less—stands in handsome grounds, amid a broad sea of closely barbered, unreal-looking grass. A creamy-white and many-windowed cube, it looks like nothing so much as an old-style ocean-going luxury liner viewed head-on, complete with big flag whipping importantly in the breeze and air-conditioning vents that might be smoke-stacks. Since childhood I have secretly entertained the idea of hospitals as places of romantic enchantment, an idea which no number of drear visits and more than a few brief but unpleasant stays have managed to disabuse me of entirely. I trace this fancy to an autumn afternoon when I was five or six and my father took me on the bar of his bicycle to the Fort Mountain outside our town, where we sat in the bracken on a steep slope eating bread-and-butter sandwiches and drinking milk from a lemonade bottle that had been corked with a screw of greaseproof paper. The TB hospital loomed high up behind us, cream-coloured also, and also many-windowed, on the unseen terraces of which I imagined neat rows of pale girls and neurasthenic young men, too refined and fastidious to live, reclining on extended deckchairs under bright-red blankets, drowsing and fitfully dreaming. Even the smell of a hospital suggests to me an exotically pristine world where specialists in white coats and sterile masks move silently among narrow beds overhung with phials feeding priceless ichor drip by drip into the veins of fallen moguls and, yes, afflicted film stars.

It was pills Dawn Devonport took, a whole bottle of them. Pills are, I note, the preferred choice among our profession, I wonder why. There is a question as to the seriousness of her intention. But an entire bottle, that is impressive. What did I feel? Dread, confusion, a certain numbness, a certain annoyance, too. It was as if I had been strolling unconcernedly along an unfamiliar, pleasant street when suddenly a door had been flung open and I had been seized by the scruff and hauled unceremoniously not into a strange place but a place that I knew all too well and had thought I would never be made to enter again; an awful place.

When I first walked into the hospital room—crept, would be a better word—and saw this hitherto so vivid young woman lying there still and gaunt my heart gave a gulp, for I thought that what they had told me must be mistaken and that she had succeeded in what she had set out to do and that this was her corpse, laid out ready for the embalmers. Then she gave me an even greater start by opening her eyes and smiling—yes, she smiled, with what at first seemed to me pleasure and genuine warmth! I did not know whether to take this for a good sign or a bad. Had she lost her reason to desperation and despair, to be lying there in a hospital bed smiling like that? Looking closer I saw, however, that it was less a smile than a grimace of embarrassment. And in fact that was the first thing she said, struggling to sit up, that she felt embarrassed and disgraced, and she put out a trembling hand for me to take. Her skin was hot, as if she were running a fever. I set up her pillows for her and she lay back on them with a groan of anger against herself. I noted the plastic name-tag around her wrist, and read the name on it. How tiny she looked, tiny and hollowed out, propped there weightless-seeming as a fledgling fallen from the nest, her enormous eyes starting from her head and her hair lank and drawn back and her sharp bones pressing into the shoulders of the washed-out, drab-green hospital gown. Those big hands of hers appeared bigger than ever, the fingers stubbier. There were flakes of dried grey stuff at the corners of her mouth. What turbulent depths had she leaned out over, what windy abyss had called to her?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ancient Light»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ancient Light» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ancient Light» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.