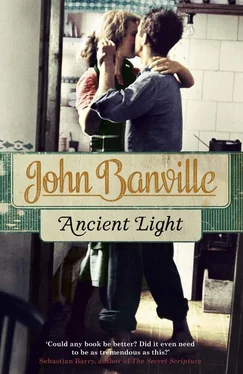

John Banville - Ancient Light

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Banville - Ancient Light» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Viking Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ancient Light

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-670-92061-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Light: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ancient Light»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

gives us a brilliant, profoundly moving new novel about an actor in the twilight of his life and his career: a meditation on love and loss, and on the inscrutable immediacy of the past in our present lives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq-oMYIS44o

Ancient Light — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ancient Light», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I know,’ she said ruefully. ‘I look like my mother did on her deathbed.’

I had not been at all sure that I should come. Did I know her well enough to be here? In such circumstances, where cheated death lingers rancorously, there is a code of etiquette more iron-bound than any that applies outside, in the realm of the living. Yet how could I not have come? Had we not achieved an intimacy, not only in front of the camera but away from it, too, that went far beyond mere acting? Had we not shared our losses, she and I? She knew about Cass, I knew about her father. Yet there was the question whether precisely this knowledge would hover between us like a troublesome, doubled ghost, and strike us mute.

What did I say to her? Cannot think: mumbled some trite condolence, no doubt. What would I have said to my daughter if she had somehow survived those slimed, rust-coloured rocks at the foot of that headland at Portovenere?

I drew a plastic chair to the bedside and sat down, leaning forwards with my forearms on my knees and my hands clasped; I must have looked a father-confessor to the life. One thing I was certain of: if Dawn Devonport mentioned Cass I would get up from that chair without a word and walk out. Around us the many noises of the hospital were joined together in a medleyed hum, and the air in the overheated room had the texture of warm damp cotton. Through the window on the far side of the bed I could see the mountains, distant and faint, and, closer in, an extensive building site with cranes and mechanical diggers and many foreshortened workmen in helmets and yellow safety-jackets clambering about in the rubble. It does not know how heartless it is, the workaday world.

Dawn Devonport had withdrawn the hand that she had briefly given me and it lay now limp at her side, pallid as the sheet on which it rested. The name on the plastic identity bracelet was not hers, I mean the name that was printed there was not Dawn Devonport. She saw me looking and smiled again, grimly. ‘That’s me,’ she said in a Cockney voice, ‘my real name, Stella Stebbings. Bit of a tongue-twister, ain’t it?’

At noon a maid had discovered her in the bedroom of her hotel suite at Ostentation Towers, the curtains drawn and she sprawled halfway out of a disordered bed with foam on her lips and the empty pill bottle clasped in her fist. I could see the scene, blocked out in classic fashion, under, of course, in my vision of it, the suggestion of a proscenium arch, or in this case, I suppose, within the rectangle of a sombrely glowing screen. She did not know why she had done it, she said, reaching out her hand again and fixing it on my clasped fists, as it was broad enough to do—they must be her father’s hands she has. She supposed, she said, that she had acted on impulse, yet how could that be, she wanted to know, when it had taken such an effort to swallow all those pills? They were a very mild dose, otherwise she would certainly be dead, the doctor had assured her of it. He was an Indian, the doctor, mild-mannered and with such a sweet smile. He had seen her as Pauline Powers in the remake of Bitter Harvest . That had been one of her father’s favourite pictures, the original version, though, with Flame Domingo playing Pauline. It was her father who had encouraged her to be a film actress. He had been so proud to see his daughter’s name in lights, the very name he had dreamed up for her when she was a fleet-footed prodigy in cellophane wings and a tutu. The shell of her hand tightened over both of mine, and I unclasped my fingers and turned up one of my hands and felt her palm hot against mine, and as if this touch between us were scalding she snatched her hand away again and sat forwards, making a tent of her knees, and looked out of the window, a moist sheen on her forehead and her hair hooked behind her ears and that penumbral down on her skin all aglow and her eyes lit with a fevered gleam. Sitting there like that, so erect and stark with her profile etched against the light, she had the look of a primitive figure carved from ivory. I imagined tracing the line of her jaw with a fingertip, imagined placing my lips against the side of her smooth, shadowed throat. She was Cora, Vander’s girl, and I was Vander: she the damaged beauty, I the beast. We had been acting their savage love for weeks now: how could we not in some way be them? She began to weep, the big glistening tears making grey splashes on the sheet. I pressed her hand. She should go away, I told her, in a voice thick with an emotion I was too moved to try to identify—she should have Toby Taggart call a week-long, a month-long halt to the filming and get away from everything altogether. She was not listening. The far-off mountains were blue, like motionless pale smoke. My lost girl , Vander calls her in the script. My lost girl.

Careful.

In the end we had not much to say to each other—should I have given her a stern talking-to, should I have urged her to cheer up and look on the bright side of things?—and after a short while I left, saying I would come again tomorrow. She was still far away in herself or in those far blue hills and I think she hardly noticed my going.

In the corridor I encountered Toby Taggart, loitering uneasily, fidgeting and biting his nails and looking more than ever like a wounded ruminant. ‘Of course,’ he burst out straight off, ‘you’ll think I’m only worried about the shoot.’ Then he looked abashed and set to nibbling again violently at a thumbnail. I could see he was putting off going in to see his fallen star. I told him of how when she had woken up she had smiled at me. He took this with a look of large surprise and, I thought, a trace of reprehension, though whether it was Dawn Devonport’s hardly appropriate smile or my telling him about it that he deplored I could not say. To distract myself in my shaken state—I had a fizzing sensation all over, as if a strong electric current were passing along my nerves—I was thinking what a vast and complicated contraption a hospital is. An endless stream of people kept walking past us, to and fro, nurses in white shoes with squeaky rubber soles, doctors with dangling stethoscopes, dressing-gowned patients cautiously inching along and keeping close to the walls, and those indeterminate busy folk in green smocks, either surgeons or orderlies, I can never tell which. Toby was watching me but when I caught his eye he looked aside quickly. I imagine he was thinking of Cass, who had succeeded where Dawn Devonport had failed. Was he thinking too, guiltily, of how he had sent Billie Stryker to lure her story out of me? He has never let on that he knows about Cass, has never once so much as mentioned her name in my presence. He is a wily fellow, despite the impression he likes to give of being a shambler and dim.

There was a long rectangular window beside us affording a broad view of roofs and sky and those ubiquitous mountains. In the middle distance, among the chimney pots, the November sunlight had picked out something shiny, a sliver of window-glass or a steel cowling, and the thing kept glinting and winking at me with what seemed, in the circumstances, a callous levity. Just to be saying something I asked Toby what he would do now about the film. He shrugged and looked vexed. He said he had not yet told the studio what had happened. There was a great deal of footage already in the can, he would work on that, but of course there was the ending still to be shot. We both nodded, both pursed our lips, both frowned. In the ending as it is written Vander’s girl Cora drowns herself. ‘What do you think?’ Toby asked cautiously and still without looking at me. ‘Should we change it?’

An ancient fellow in a wheelchair was bowled past, white-haired, soldierly, one eye bandaged and the other furiously staring. The wheels of the wheelchair made a smoothly pleasant, viscous whispering on the rubber floor tiles.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ancient Light»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ancient Light» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ancient Light» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.