I was in the kitchen. I might never have been here before. Or I might have been, but in another dimension. Talk about making strange! Everything was askew. It was like entering backstage and seeing the set in reverse, all the parts of it known but not where they should be. Where were my chalk-marks now, my blocked-out map of moves? I was seized by a peculiar cold excitement, the sort that comes in dreams, at once irresistible and disabling. If only I could creep up on the whole of life like this, and see it all from a different perspective! The door to the basement scullery was shut; from behind it could be heard the faint clink and scrape of Quirke at his victuals. Softly I stepped into the passageway leading out to the front hall. A gleam in the lino transported me on the instant, heart-shakingly, to a country road somewhere, in April, long ago, at evening, with rain, and breezes, and swooping birds, and a break of brilliant blue in the far sky shining on the black tarmac of the road. Here is the front hall, with its fern dying in a brass pot, and a broken pane in the transom, and Quirke’s increasingly anthropomorphic bike leaning against the hatstand. Here is the staircase, with a thick beam of sunlight hanging in suspended fall from a window on the landing above. I stood listening, and seemed listened back to by the silence. I set off up the stairs, feeling the faintly repulsive clamminess of the banister rail under my hand, offering me its dubious intimacy. I went into my mother’s room, and sat on the side of my mother’s bed. There was a dry smell, not unpleasant, as if something ripe had rotted here and turned to dust. The bedclothes were awry, a pillow bore a head-shaped hollow. Through the window I looked out to the far blue hills shimmering in rain-rinsed air. So I remained for a long moment, listening to the faint sounds of the day, that might have been the tumult of a far-off battle, not thinking, exactly, but touching the thought of thought, as one would touch the tender, buzzing edges of a wound.

Cass was good with my mother. It always surprised me. There was something between them, a complicity, from which I was irritated to find myself excluded. They were alike, in ways. What in my mother was distraction turned out in Cass to be an absence, a lostness. Thus the march of the generations works its dark magic, making its elaborations, its complications, turning a trait into an affliction. Cass would sit here for hours with the dying woman at the end, seeming not to mind the smell, the foulings, the impenetrable speechlessness. They communed in silence. Once I found her asleep with her head on my mother’s breast. I did not wake her. Over the sleeping girl my mother watched me with narrow malignity. Cass was always an insomniac, worse than me. Sleep to her was a dry run for death. Even as a toddler she would make herself stay awake into the small hours, afraid of letting go, convinced she would not wake up again. I would look into her room and find her lying big-eyed and rigid in the darkness. One night when I—

The door was opened from without and Quirke cautiously put in his head. When he saw me his Adam’s apple bobbed.

“I thought I heard someone, all right,” he said, and let a grey tongue-tip snake its way from one corner of his mouth to the other.

I went down again to the hall and sat on the sofa there with my hands in my lap. I could hear Quirke moving about upstairs. I stood up and walked into the kitchen and leaned at the sink and poured a glass of water and drank it slowly, swallow by long swallow, shivering a little as the liquid ran down through the branched tree in my breast. I glanced into the scullery. On the table were the remains of Quirke’s lunch. What pathos in a crust of bread. I heard him come along the hall and stop in the doorway behind me.

“You’re living here,” I said, “aren’t you?”

I turned to him, and he grinned.

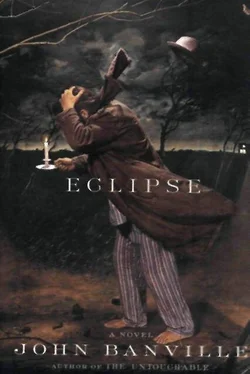

I pause, as a chronicler should, to record the imminence of a great event. There is to be a solar eclipse. Total occlusion is predicted, though not for all. The Scandinavians are not to get a look-in, likewise the inhabitants of the Antipodes. Even within the relatively narrow band over which the moon’s cloak will sweep, there are to be appreciable variations. In this latitude it is expected we shall have about ninety-five per cent coverage of the disc. For others, however, notably the beggars on the streets of Benares, a treat is in store: they are to enjoy approximately two and a half minutes of noontime night, the longest to be experienced anywhere on the globe. I deplore the lack of precision in these forecasts. Today, when there are clocks that work on the oscillations of a single atom, one surely might expect better than about ninety-five per cent, or approximately two and a half minutes—why are these things not being measured in nanoseconds? Yet people are agog. Tens of thousands are said to be already on the move, flocking to the rocky coasts of the south, on which the full shadow will fall. I wish I could share their enthusiasm; I should like to believe in something, or at least be in expectation of something, even if only a chance celestial conjunction. I see them, of course, as a great band of pilgrims out of an old tale, trudging down the dusty roads with staff and bell, archaic faces alight with longing and hope. And I, I am the scoffer, lounging in doublet and hose in an upstairs window of some half-timbered inn, languidly spitting pomegranate seeds on their bowed heads as they pass below me. They yearn for a sign, a light in the sky, a darkness, even, to tell them that things are intended, that all is not blind happenstance. What would they not give for a glimpse of my ghosts? Now, there is a sign, there is a portent, of what, I am still not sure, although I am beginning to have my suspicions.

I was right, they have been here all along, the two of them, Quirke and the girl. I am more baffled than indignant. How did they manage it without my noticing? Haunted, I was ever on the watch for phantoms, how then could I overlook the presence of two of the living? But perhaps the living are not my kind, any more, perhaps they do not register with me as once they would have done. Quirke of course is embarrassed to have been found out, but I can see from his look that he is amused, too, in a rueful sort of way. When I confronted him there in the kitchen he looked me boldly in the eye, still grinning, and said he had considered it a perk of the job of caretaker that he and his girl should be allowed to live on the premises. I was so taken aback by the brazenness of this that I could think of nothing to say in reply. He went on to assure me that he had kept up the charade only out of a desire that I should not be disturbed; I would have laughed, in other circumstances. Nor has he offered to move out. He sauntered off, quite breezy, whistling through his teeth, and presently appeared at the door on his bicycle as usual, and he and Lily straggled away into the twilight quite as they have done every evening. Later, when I was in bed, I heard them stealthily returning. These must be the sounds I have been hearing every night since I came here, and which I failed to interpret. How simple and dull and disappointing things become when they are explained; maybe my ghosts will yet step forward, bowing and smirking, and I shall be allowed to see the mirrors and the smoke.

How the two of them—Quirke and Lily, I mean—how they pass the hours between their twilight departure and their return in the dark I cannot say. Lily goes to the pictures, I suppose, or to the disco—there is one somewhere nearby, half the night I feel its dull pulse drumming through the air—while Quirke haunts the pub; I can see him, with his pint and his cigarette, chaffing the barmaid, or gloomily ogling the bare-chested lovelies in someone else’s discarded newspaper. I asked him where it is in the house that he and Lily sleep and he shrugged and said with deliberate vagueness that they bunk down wherever is handy. I believe it is the girl who sometimes uses my mother’s bed. I do not know what to think of this. It is not yet acknowledged, between Lily and me, that I know her secret. Something prevents me from mentioning it, an obscure squeamishness. There are no rules of etiquette to cover a situation such as this. Although Quirke must have told her I am on to them, for her part she goes on just as before, with the same air of general resentment and bored disinclination.

Читать дальше