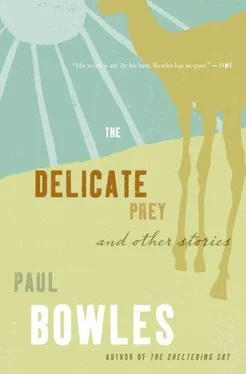

Paul Bowles - The Delicate Prey - And Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Bowles - The Delicate Prey - And Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:9780062119346

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She put her hand in front of her face. “My eyes are ugly.”

“It’s not true!” he declared with indignation. Then, “They’re beautiful,” he added, after looking at them carefully for a moment.

She saw that he was not making fun of her, and straightway decided that she liked him more than any boy she had ever known.

That night he told his aunt about Luz, and as he described the colors in her face and hair he saw her look pleased. “Una hija del soil” she exclaimed. “They bring good luck. You must invite her here tomorrow. I shall prepare her a good refresco de tamarindo.” Nicho said he would, but he had no intention of subjecting his friend to his aunt’s interested scrutiny. And while he was not at all astonished to hear that albinos had special powers, he thought it selfish of his aunt to want to profit immediately by those which Luz might possess.

The next day when he went to the bridge and found Luz standing there, he was careful to lead her through a hidden lane down to the water, so that she might remain unseen as they passed near the house. The bed of the river lay largely in the shadows cast by the great trees that grew along its sides. Slowly the two children wandered downstream, jumping from rock to rock. Now and then they startled a vulture, which rose at their approach like a huge cinder, swaying clumsily in the air while they walked by, to realight in the same spot a moment later. There was a particular place that he wanted to show her, where the river widened and had sandy shores, but it lay a good way downstream, so that it took them a long time to get there. When they arrived, the sun’s light was golden and the insects had begun to call. On the hill, invisible behind the thick wall of trees, the soldiers were having machine-gun practice: the blunt little berries of sound came in clusters at irregular intervals. Nicho rolled his trouser legs up high above his knees and waded well out into the shallow stream. “Wait!” he called to her. Bending, he scooped up a handful of sand from the river bed. His attitude as he brought it back for her to see was so triumphant that she caught her breath, craned her neck to see it before he had arrived. “What is it?” she asked.

“Look! Silver!” he said, dropping the wet sand reverently into her outstretched palm. The tiny grains of mica glistened in the late sunlight.

“Qué precioso!” she cried in delight. They sat on some roots by the water. When the sand was drier, she poured it carefully into the pocket of her dress.

“What are you going to do with it?” he asked her.

“Give it to my grandfather.”

“No, no!” he exclaimed. “You don’t give away silver. You hide it. Don’t you have a place where you hide things?”

Luz was silent; she never had thought of hiding anything. “No,” she said presently, and she looked at him with admiration.

He took her hand. “I’ll give you a special place in my garden where you can hide everything you want. But you must never tell anyone.”

“Of course not.” She was annoyed that he should think her so stupid. For a while she had been content just to sit there with Nicho beside her; now she was impatient to get back and deposit the treasure. He tried to persuade her to stay a little longer, saying that there would be time enough if they returned later, but she had stood up and would not sit down again. They climbed upstream across the boulders, coming suddenly upon a pool where two young women stood thigh-deep washing clothes, naked save for the skirts wrapped round their waists, long full skirts that floated gently in the current. The women laughed and called out a greeting. Luz was scandalized.

“They should be ashamed!” she cried. “In San Lucas if a woman did that, everyone would throw stones at her until she was buried under them!”

“Why?” said Nicho, thinking that San Lucas must be a very wicked town.

“Because they would,” she answered, still savoring the shock and shame she had felt at the sight of the golden breasts in the sunlight.

When they got back to town they turned into the path that led to Nicho’s house, and while they were still in the jungle end of the garden, Nicho stopped and indicated a dead tree whose trunk had partially decayed. With the gesture of a conspirator he pulled aside the fringed curtain of vines that hung down across most of it, revealing several dark holes. Reaching into one of them, he pulled out a bright tin can, flicked off the belligerent ants that raced wildly around it, and held it forth to her.

“Put it in here,” he whispered.

It took a while to transfer all the sand from her pocket to the can; when it was done he replaced it inside the dark trunk and let the vines fall straight again to cover the place. Then he conducted Luz quickly up through the garden, around the house, into the street. His aunt, having caught sight of them, called: “Dionisio!” But he pretended not to have heard her and pushed Luz ahead of him nervously. He was suddenly in terror lest Luz see Señor Ong; that was something which must be avoided at any cost.

“Dionisio!” She was still calling; she had come out and was standing in front of the door, looking down the street after them, but he did not turn around. They reached the bridge. It was out of sight of the house.

“Adiós,” he said.

“Hasta mañana,” she answered, peering up at him with her strange air of making a great effort. He watched her walk up the street, moving her head from side to side as if there were a thousand things to see, when in reality there were only a few pigs and some chickens roaming about.

At the evening meal his aunt eyed him reproachfully. He averted her gaze; she did not mention his promise to bring Luz to the house for refrescos. That night he lay on his mat watching the phosphorescent beetles. His room gave on the patio; it had only three walls. The fourth side was wide open. Branches of the lemon tree reached in and rubbed against the wall above his head; up there, too, was a huge unfolding banana leaf which was pushing its way further into the room each day. Now the patio was dizzy with the beetles’ sharp lights. Crawling on the plants or flying frantically between them, they flashed their signals on and off with maddening insistence. In the neighboring room his aunt and Señor Ong occupied the bed of the house, enjoying the privacy of quarters that were closed in on all four sides. He listened: the wind was rising. Nightly it appeared and played on the leaves of the trees, dying away again before dawn. Tomorrow he would take Luz down to the river to get more silver. He hoped Señor Ong had not been spying when he had uncovered the holes in the tree trunk. The mere thought of such a possibility set him to worrying, and he twisted on his mat from one side to the other.

Presently he decided to go and see if the silver was still there. Once he had assured himself either that it was safe or that it had been stolen, he would feel better about it. He sat up, slipped into his trousers, and stepped out into the patio. The night was full of life and motion; leaves and branches touched, making tiny sighs. Singing insects droned in the trees overhead; everywhere the bright beetles flashed. As he stood there feeling the small wind wander over him he became aware of other sounds in the direction of the sala. The light was on there, and for a moment he thought that perhaps Señor Ong had a late visitor, since that was the room where he received his callers. But he heard no voices. Avoiding the lemon tree’s sharp twigs, he made his way soundlessly to the closed doors and peered between them.

There was a square niche in the sala wall across which, when he had first arrived, Señor Ong had tacked a large calendar. This bore a colored picture of a smiling Chinese girl. She wore a blue bathing suit and white fur-topped boots, and she sat by a pool of shiny pink tiles. Over her head in a luminous sky a gigantic four-motored plane bore down upon her, and further above, in a still brighter area of the heavens, was the benevolent face of Generalissimo Chiang. Beneath the picture were the words: ABARROTES FINOS. Sun Man Ngai, Huixtla, Chis. The calendar was the one object Señor Ong had brought with him that Nicho could wholeheartedly admire; he knew every detail of the picture by heart. Its presence had transformed the sala from a dull room with two old rocking chairs and a table to a place where anything might happen if one waited long enough. And now as he peeked through the crack, he saw with a shock that Señor Ong had removed the calendar from its place on the wall, and laid it on the table. He had a hammer and a chisel and he was pounding and scratching the bottom of the niche. Occasionally he would scoop out the resulting plaster and dust with his fat little hands, and dump it in a neat pile on the table. Nicho waited for a long time without daring to move. Even when the wind blew a little harder and chilled his naked back he did not stir, for fear of seeing Señor Ong turn around and look with his narrow eyes toward the door, the hammer in one hand, the chisel in the other. Besides, it was important to know what he was doing. But Señor Ong seemed to be in no hurry. Almost an hour went by, and still tirelessly he kept up his methodical work, pausing regularly to take out the debris and pile it on the table. At last Nicho began to feel like sneezing; in a frenzy he turned and ran through the patio to his room, scratching his chest against the branches on the way. The emotion engendered by his flight had taken away his desire to sneeze, but he lay down anyway for fear it might return if he went back to the door. In the midst of wondering about Señor Ong he fell asleep.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Delicate Prey: And Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.