The girl who first fell was left behind by events now. She still felt less than well, still had tremors in her hands at times, attacks of fatigue, which her doctor said were due to stress, and which a medical person, who preferred not to be named by the media, suggested could be the after-effects of nerve gas poisoning. But she was no longer a focus of attention.

She sat in her room and stared at the cover of her exercise book, where she had written Bible Themes in Literature , and filled in the circles of the B with her pen. Then she opened it to the first page and wrote Book of Genesis . Paused and checked her cellphone for text messages, picked up her pen again. Located in garden , she wrote. V. signif , then closed the notebook and picked up the phone.

‘Oh my God,’ said Nicole.

‘Did you see the show last night?’

‘I cried. Seriously I did.’

‘If Luke and Lorelai don’t get together I’m honestly going to die. I’m not even kidding. Did you see where he… ’

‘Oh my God. I so did. I was like dead.’

She doodled a heart on her notebook and wrote Luke inside, then scribbled over it.

‘So are you doing this Bible themes thing? Do you even get what this garden thing is all about?’

‘Well, sort of innocence and stuff, right? So when there’s, like, vegetation in literature it’s like this innocence thing? You know what I mean?’

‘Yeah, but I just think that’s kind of fucked up.’

On the small TV across from her bed, which was playing quietly in the background, she saw, yet again, the footage of the girl with the braided wool bracelet, covering her eyes. She reached for the remote and changed the channel.

She remembered how it felt to fall, the sickness and the narrowing vision; but as well, though she had no words to express this, the slow pleasure of her surrender to the body’s weight, a strange sweet chemical rush as her muscles released.

Those who did not believe in the man with the poison gas had settled on iron-deficiency anemia as the meaning of her fall, and it is true that the girl’s hematocrit and serum iron were not in balance, that she ate french fries and drank Coke and avoided red meat and baked beans and multivitamins. But the girl herself knew something different. She knew she had been singled out at that moment in the subway. That she would always be, at least in some small way, the girl who fell down and started it all, and she knew there was a reason for that.

But there was no one she could talk to about it, no one who would understand why, and though she herself had only said that she smelled roses and fell, the story about poison gas and evil motives gathered around her with no effort on her part. She allowed it to happen.

Sometimes, in her room by herself, she considered other meanings. She thought that there would be a change in her life, not now, but someday, and this would be part of it. She took her iron supplements and saw, on TV, the others falling.

The rain picked up strength and began to fling itself against the windows, washing the snow down into the gutters, eating away at the low, piled drifts. A little later in the winter, a few degrees colder, it would have coated the snow with a hard layer of shining ice, and in the morning the streets would have sparkled white and silver, tree branches like black engravings on the sky, but it was not yet that time, not fully within the season.

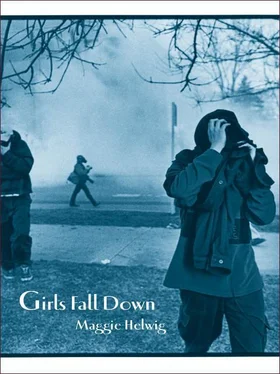

The roof of Alex’s building wasn’t supposed to be accessible to tenants, but the landlord often forgot to lock the access door. And it hurt no one for him to be here, huddled against the icy rain in his coat and hat, looking out over the street lights and the trees, the peaked and gabled Victorian houses, the downward slant of College towards the Portuguese Centre and the little strip mall and the basement where the Apocalypse Club used to be. The lens of his camera dripping with water, the water becoming a part of the picture, streaking and smearing the yellow glow of windows across the darkness. The slick hiss of the cars below as they slid through puddles, someone running under a dark umbrella. He sat on the roof, sodden, focused, a single point, and the fugitive light fell through him.

The next morning a man, a forty-five-year-old insurance broker, fell to his knees as he was getting off a train at the King station. He didn’t faint, but lay in a crouch in the doorway of the train, gasping for breath, his face turning purple. A man in one of the seats nearby grabbed at his own throat, and moaned, and slid down to the floor. Alarms began to sound.

‘Sedentary middle-aged men,’ said Walter Yee, standing by the operating table and watching one of his residents crack open a patient’s chest. ‘Both moderately overweight. You can’t tell me there wasn’t cardiac involvement. Were they put through complete stress tests?’

‘Two simultaneous cardiac episodes? Does that seem likely?’

‘Okay, I’ll grant you one psychosomatic reaction. But I’d like to see the test results on that first man.’

‘Dr. Ryvat in pulmonary thinks it was asthma,’ said one of the nurses. ‘Dr. Lissman in neurology thinks –‘

‘Okay, okay. When you’re a hammer everything looks like a nail. I’d still like to see the tests.’

Thursday morning, and Alex was standing in a corner of the OR, waiting for the preliminaries to be finished before he moved in towards the table.

‘Wow,’ said Walter, peering into the chest cavity. ‘Talk about accidents waiting to happen. Alex, come on over here and get some horrible-example photos.’

‘People in general still think it’s poisoning,’ said the anaesthetist.

‘There is no such thing as people in general,’ said Walter. ‘It’s okay, Adina, you go ahead, I’ll just keep an eye.’

‘Of course there’s such a thing.’

‘No, that’s sloppy thinking. There are only many people in particular.’

‘Fine. Many people in particular think it’s poisoning.’

‘I’ve heard disease as well. There’s a bird flu theory floating around.’

‘Oh, give me a break.’

Alex was standing near the resident, watching her hands, when she faltered and paused.

‘Really,’ said Walter. ‘You’re fine for this, Adina. You are.’ The resident looked up at him, looked back at the patient’s heart and started to cut, then her hands stopped moving and Walter jumped forward, pushing her aside, reaching into the chest.

‘Okay, okay. We can fix this,’ he said, and grabbed something from the instrument tray, his eyes on the opened chest. ‘Excuse me, why am I not getting suction here?’ he shouted. ‘Jesus Christ, people! David, why aren’t you clamping?’

Alex saw the chest cavity filling with blood. He focused the lens and took a series of fast pictures.

‘We can do this,’ said Walter. And the photographs changed too, subtly, in their purpose, being part of the documentation now that Walter and Adina had done everything right as far as they could, that there were no gross errors but only the limits of the body; or else that there had been preventable error, that something human had intervened and broken down in disaster. Alex himself didn’t know clearly what was happening, but he knew just enough to take the right pictures, pictures that would help to lay out the story when it would have to be told.

Alex had not often seen people die. But it had happened – he was part of that strange elite in Western society, one of the witnesses. This man did not die, he was not exactly dead when he left the OR, but Walter was silent and grim, and whatever would happen over the next few hours, it was clear he expected nothing good.

Читать дальше