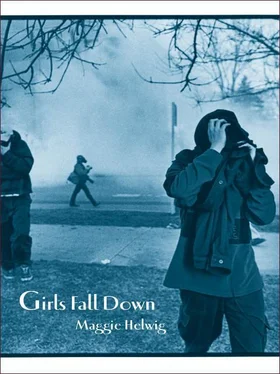

Maggie Helwig

GIRLS FALL DOWN

for David Barker Maltby,

photographer

The city is a winter city, at its heart. Though the ozone layer is thinning above it, and the summers grow long and fierce, still the city always anticipates winter. Anticipates hardship. In the winter, when it is raw and grey and dim, it is itself most truly.

People come here from summer countries and learn to be winter people. But there are worse fates. That is exactly why many of them come here, because there are far worse fates than winter.

It is a city that burrows, tunnels, turns underground. It has built strata of malls and pathways and inhabited spaces like the layers in an archaeological dig, a body below the earth, flowing with light. People turn to buried places, to successive levels of basements, lowered courtyards, gardens under glass. There are beauties to winter that are unexpected, the silence of snow, the intimacy with which we curl around places of warmth. Even the homeless and the outcasts travel downwards when they can, into the ravines that slice around and under the streets, where the rivers, the Don and the Humber and their tributaries, carve into the heart of the city; they build homes out of tents and slabs of metal siding, decorate them with bicycle wheels and dolls on strings and boxes of discarded books, with ribbons and mittens, and huddle in the cold beside the thin water.

It is hard to imagine this city being damaged by something from the sky. The dangers to this city enter the bloodstream, move through interior channels.

The girl was kneeling by the door of the subway car, a circle of friends surrounding her like birds. Her hands were over her narrow face, she was weeping, and there were angry red welts across her cheeks, white circles around them. Her friends touched her back, her arms, their voices an anxious chirp. There was a puddle of vomit at her feet, and she lowered one hand to wipe her mouth, leaning against the door.

A space had already cleared around them. Some of the passengers in the nearby seats held hands or tissues discreetly over their mouths, but as if this were incidental, as if they weren’t quite aware of anything. As the train rocked through the tunnel, a bubble of light between the dark walls, a few people got to their feet and moved down the car.

The train came into Bloor station and jerked to a stop, and the girl leaned backwards, the pool of vomit spreading, her friends lifting up their feet with little cries. As the door opened, a mass of people on the platform surged forward, then stopped, moved back into the crush and towards another car, their eyes turned politely away.

A grey-haired man in a dark coat stood up and walked to where the girls were standing. ‘Does she have an EpiPen?’ he asked.

‘A what? What’s that?’ A tall girl brushed blonde hair from her eyes. Another girl was hanging on to the metal pole, resting her forehead against it, her red tie hanging straight down, her plaid kilt rolled up at the waist, brushing her thighs. The train wasn’t moving on.

‘An EpiPen. For allergies.’

‘I’m not allergic,’ said the sick girl. The man bent down to look at her rash, keeping a slight distance between them. ‘She smelled something,’ the tall girl said. ‘There’s a gas in the car or something. They should tell somebody.’ She kept talking, but at the same time the PA system gave a quick shriek, and a distorted voice announced that the train was out of service. Beyond the door of the subway car, the crowd began to move like a huge resigned sigh, pushing towards the stairways.

‘They’ll have paramedics here soon,’ said the man. He was about to leave, it seemed, when the dark-haired girl who had been holding on to the pole suddenly swayed and put out one hand, falling to the muddy floor. The other one, the tall blonde, dropped to her knees beside her friend, crying her name.

The man knelt down, frowning. ‘If you want, I could call –’ ‘Go away,’ whimpered the first girl, dabbing at tears on her welt-covered face. ‘Go away, it’s too awful. It’s not right.’

‘It’s poison,’ cried a girl with curly rust-coloured hair. ‘Somebody put a poison in the train.’

The girl who had just fallen lay with her eyes closed. She too was covered with a rash, but a different one, a red prickly flush all over her face and hands.

‘Someone put a poison gas on the train,’ shouted the tall girl, trying to lift up her friend. The crowd outside the train heard her, and the volume of their voices increased, heads turning, some people stopping where they were. The man held his breath for a second; then, as if seized by an uncontrollable impulse, he sniffed the air, deeply.

‘What was it like, the smell?’ he asked the kneeling girl.

The station was being cleared now, the crowd on the platform fragmenting, breaking into individuals, a blur of brown and beige skin tones, splashes of bright-coloured fabric, patterns and stripes. Announcements were sounding over the PA system, men in uniform appearing, moving people quickly to the exits. A slender woman with plastic bags in her hand stood still and stared at the train, her mouth partly open.

The girl who had fallen was sitting halfway up, clinging again to the pole. ‘Roses,’ she said. ‘It smelled like roses.’

A heavy-set man sat down hard at the top of the stairs, his face suffused with blood, gasping for breath, and a stranger took hold of his arm and pulled him along as far as the fare booth, where he stumbled and fell.

The girl was creeping towards the door of the train, stopping to wipe at the smears of vomit on her legs, and her friend was sitting up, dazed, leaning her head against the tall girl’s chest. On the level above, a woman took off her parka and bundled it underneath the head of the man by the fare booth.

The man in the dark coat started to put a hand out towards one of the girls, and then pulled it back. He looked up and saw the security guards arriving. ‘They’re coming now,’ he said, ‘you’ll be okay,’ and left the train, heading for the stairs. As he went up, the first team of paramedics pushed past him, carrying an orange stretcher, a policewoman watching from the upper level.

‘They smelled a gas,’ someone was saying at the top of the stairs. The paramedics lifted the first girl onto the stretcher. ‘Roses,’ she said.

One of the girls said, ‘Poison,’ again. The woman with the plastic bags was still frozen on the platform. Then she swayed, fell to her knees.

‘Jesus!’ crackled the voice on the PA, someone forgetting he was in front of a live mike. ‘There’s four of them down now. What the hell’s going on here?’

The man at the fare booth told someone that he thought it was his heart, he was pretty sure it was his heart, but when he thought about it he did remember the smell. Yes. The smell of roses.

As more paramedics arrived, a policewoman placed the first call for a hazmat team.

The corridor was narrow and badly lit, the arms of the mall branching off in odd directions, and the stairs were filled now with more police and paramedics coming down, wearing face masks, as the crowd, expelled from the subway, made their way up. No one was paying attention to Alex, as he slid through the turnstile and up the stairs to the mall – and why should they, he was ordinary and forgettable, a thin man who looked much older than thirty-nine, wearing a reasonably good dark coat, his prematurely grey hair cut short. He ducked into the drugstore on his right, hoping it would carry disposable cameras – pieces of shit, they were, he’d never get a decent picture, but at least he’d have a camera-like object in his hands, at least he’d be able to think.

Читать дальше