The Collingwood still smelled of paint. As she let herself in at the front door, kicking off her shoes, it caught in her throat and mingled with the taste of salt and phlegm. She went upstairs to her own room—Bed Two, 15 by 14 feet with en-suite shower—and slammed the door, and sat down on the bed. Her little shoulders shook, she pressed her knees together; she clenched her fists and pressed them into her skull. She cried quite loudly, thinking Al might hear. If Al opened the bedroom door she would throw something at her, she decided—not anything like a bottle, something like a cushion—but there wasn’t a cushion. I could throw a pillow, she thought, but you can’t throw a pillow hard. I could throw a book, but there isn’t a book. She looked around her, dazed, frustrated, eyes filmed and brimming, looking for something to throw.

But it was a useless effort. Al wasn’t coming, not to comfort her: nor for any other purpose. She was, Colette knew, selectively deaf. She listened into spirits and to the voice of her own self-pity, carrying messages to her from her childhood. She listened to her clients, as much as was needful to get money out of them. But she didn’t listen to her closest associate and personal assistant, the one who got up with her when she had nightmares, the friend who boiled the kettle in the wan dawn: oh no. She had no time for the person who had taken her at her word and given up her career in event management, no time for the one who drove her up and down the country without a word of complaint and carried her heavy suitcase when the bloody wheels fell off. Oh no. Who carried her case full of her huge fat clothes—even though she had a bad back.

Colette cried until two red tracks were scored into her cheeks, and she got hiccoughs. She began to feel ashamed. Every lurch of her diaphragm added to her indignity. She was afraid that Alison, after her deafness, might now choose to hear.

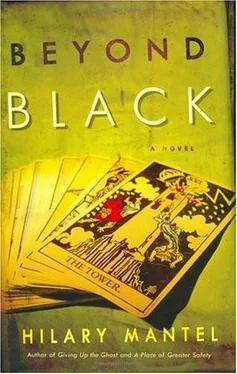

Downstairs, Al had her tarot pack fanned out before her. The cards were face down, and when Colette appeared in the doorway she was idly sliding them in a rightward direction, over the pristine surface of their new dining table.

“What are you doing? You’re cheating.”

“Mm? It’s not a game.”

“But you’re fixing it, you’re shoving them back into the pack! With your finger! You are!”

“It’s called Washing the Cards,” Al said. “Have you been crying?”

Colette sat down in front of her. “Do me a reading.”

“Oh, you have been crying. You have so .”

Colette said nothing.

“What can I do to help?”

“I’d rather not talk about it.”

“So I should make general conversation?”

“If you like.”

“I can’t. You start.”

“Did you have any more thoughts about the garden?”

“Yes. I like it as it is.”

“What, just turf?”

“For the moment.”

“I thought we could have a pond.”

“No, the children. The neighbours’ children.”

“What about them?”

“Cut the pack.”

Colette did it.

“Children can drown in two inches of water.”

“Aren’t they ingenious?”

“Cut again. Left hand.”

“I could get some quotes for landscaping.”

“Don’t you like grass?”

“It needs cutting.”

“Can’t you do it?”

“Not with my back.”

“Your back? You never mentioned it.”

“You never gave me the chance.”

“Cut again. Left hand, Colette, left hand. Well, I can’t do it. I’ve got a bad back too.”

“Really? Where did that originate?”

“When I was a child.” I was dragged, Alison thought, over the rough ground.

“I’d have thought it would have been better.”

“Why?”

“I thought time was a great healer.”

“Not of backs.”

Colette’s hand hovered.

“Choose one,” Al said. “One hand of seven. Seven cards. Hand them to me.” She laid down the cards. “And your back, Colette?”

“What?”

“The problem. Where it began?”

“Brussels.”

“Really?”

“I was carrying fold-up tables.”

“That’s a pity.”

“Why?”

“You’ve spoiled my mental picture. I thought that perhaps Gavin had put you in some unorthodox sexual position.”

“How could you have a picture? You don’t know Gavin.”

“I wasn’t picturing his face.” Alison began to turn the cards. The lucky opals were flashing their green glints. Alison said, “The Chariot, reversed.”

“So what do you want me to do? About the garden?”

“Nine of swords. Oh dear.”

“We could take it in turns to mow it.”

“I’ve never worked a mower.”

“Anyway, with your weight. You might have a stroke.”

“Wheel of Fortune, reversed.”

“When you first met me, in Windsor, you said I was going to meet a man. Through work, you said.”

“I don’t think I committed to a time scheme, did I?”

“But how can I meet a man through work? I don’t have any work except yours. I’m not going out with Raven, or one of those freaks.”

Al fluttered her hand over the cards. “This is heavy on the major Arcana, as you see. The Chariot, reversed. I’m not sure I like to think of wheels turning backward … . Did you send Gavin a change-of-address card?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“As a precaution.”

“Sorry?”

“Something might come for me. For forwarding. A letter. A package.”

“A package? What would be in it?”

Al heard tapping, tapping, at the sliding glass doors of the patio. Fear jolted through her; she thought, Bob Fox. But it was only Morris, trapped in the garden; beyond the glass, she could see his mouth moving.

She lowered her eyes, turned a card. “The Hermit reversed.”

“Bugger,” Colette said. “I think you were reversing them on purpose, when you were messing about. Washing them.”

“What a strange hand! All those swords, blades.” Al looked up. “Unless it’s just about the lawn mower. That would make some sense, wouldn’t it?”

“No use asking me. You’re the expert.”

“Colette … Col … don’t cry now.”

Colette put her elbows on the table, her head on her hands, and howled away. “I ask you to do a reading for me and it’s about bloody garden machinery. I don’t think you have any consideration for me at all. Day in, day out I am doing your VAT. We never go anywhere. We never do anything nice. I don’t think you have any respect for my professional skills whatever, and all I have to listen to is you rabbitting on to dead people I can’t see.”

Alison said gently, “I’m sorry if it seems as if I don’t appreciate you. I do remember, I know what my life was like when I was alone. I do remember, and I value everything you do.”

“Oh, stop it. Burbling like that. Being professional.”

“I’m trying to be nice. I’m just trying—”

“That’s what I mean. Being nice. Being professional. It’s all the same to you. You’re the most insincere person I know. It’s no use pretending to me. I’m too close. I know what goes on. You’re rotten. You’re a horrible person. You’re not even normal.”

There was a silence. Alison picked up the cards, dabbing each one with a damp fingertip. After a time she said, “I don’t expect you to mow the lawn.”

Silence.

“Honest, Col, I don’t.”

Silence.

“Can I be professional for a moment?”

Silence.

“The Hermit, reversed, suggests that your energy could be put to better use.”

Colette sniffed. “So what shall we do?”

“You could ring up a gardening service. Get a quote. For, let’s say, a fortnightly cut through the summer.” She added, smiling, “I expect they’d send a man.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу