GILGONGO!

In the language of the planet, that meant “Extinct!"

People were glad that the bears were gilgongo, because there were too many species on the planet already, and new ones were coming into being almost every hour. There was no way anybody could prepare for the bewildering diversity of creatures and plants he was likely to encounter.

The people were doing their best to cut down on the number of species, so that life could be more predictable. But Nature was too creative for them. All life on the planet was suffocated at last by a living blanket one hundred feet thick. The blanket was composed of passenger pigeons and eagles and Bermuda Erns and whooping cranes.

“At least it’s olives,” the driver said.

“What?” said Trout.

“Lots worse things we could be hauling than olives.”

“Right,” said Trout. He had forgotten that the main thing they were doing was moving seventy-eight thousand pounds of olives to Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The driver talked about politics some.

Trout couldn’t tell one politician from another one. They were all formlessly enthusiastic chimpanzees to him. He wrote a story one time about an optimistic chimpanzee who became President of the United States. He called it “Hail to the Chief.”

The chimpanzee wore a little blue blazer with brass buttons, and with the seal of the President of the United States sewed to the breast pocket. It looked like this:

Everywhere he went, bands would play “Hail to the Chief.” The chimpanzee loved it. He would bounce up and down.

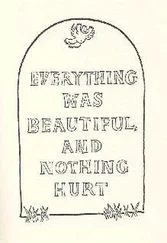

They stopped at a diner. Here is what the sign in front of the diner said:

So they ate.

Trout spotted an idiot who was eating, too. The idiot was a white male adult—in the care of a white female nurse. The idiot couldn’t talk much, and he had a lot of trouble feeding himself. The nurse put a bib around his neck.

But he certainly had a wonderful appetite. Trout watched him shovel waffles and pork sausage into his mouth, watched him guzzle orange juice and milk. Trout marveled at what a big animal the idiot was. The idiot’s happiness was fascinating, too, as he stoked himself with calories which would get him through yet another day.

Trout said this to himself: “Stoking up for another day.”

“Excuse me,” said the truck driver to Trout, “I’ve got to take a leak.”

“Back where I come from,” said Trout, “that means you’re going to steal a mirror. We call mirrors leaks."

“I never heard that before,” said the driver. He repeated the word: “Leaks.” He pointed to a mirror on a cigarette machine. “You call that a leak?”

“Doesn’t it look like a leak to you?” said Trout.

“No,” said the driver. “Where did you say you were from?”

“I was born in Bermuda,” said Trout.

About a week later, the driver would tell his wife that mirrors were called leaks in Bermuda, and she would tell her friends.

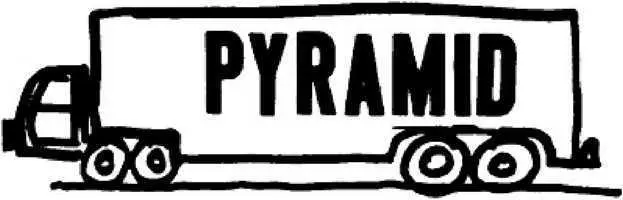

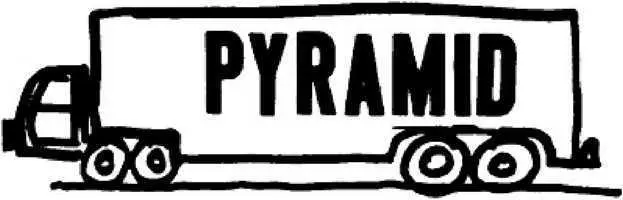

When Trout followed the driver back to the truck, he took his first good look at their form of transportation from a distance, saw it whole.

There was a message written on the side of it in bright orange letters which were eight feet high. This was it:

Trout wondered what a child who was just learning to read would make of a message like that. The child would suppose that the message was terrifically important, since somebody had gone to the trouble of writing it in letters so big.

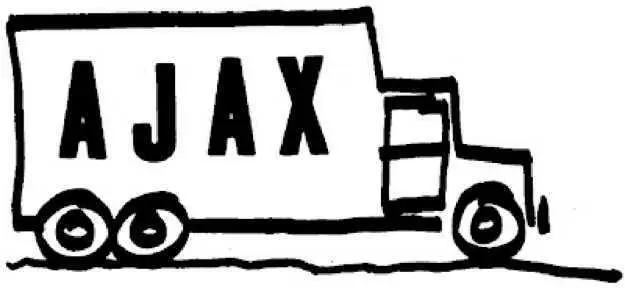

And then, pretending to be a child by the roadside, he read the message on the side of another truck. This was it:

Dwayne Hoover slept until ten at the new Holiday Inn. He was much refreshed. He had a Number Five Breakfast in the popular restaurant of the Inn, which was the Tally-Ho Room. The drapes were drawn at night. They were wide open now. They let the sunshine in.

At the next table, also alone, was Cyprian Ukwende, the Indaro, the Nigerian. He was reading the classified ads in the Midland City Bugle- Observer. He needed a cheap place to live. The Midland County General Hospital was footing his bills at the Inn while he looked around, and they were getting restless about that.

He needed a woman, too, or a bunch of women who would fuck him hundreds of times a week, because he was so full of lust and jism all the time. And he ached to be with his Indaro relatives. Back home, he had six hundred relatives he knew by name.

Ukwende’s face was impassive as he ordered the Number Three Breakfast with whole-wheat toast. Behind his mask was a young man in the terminal stages of nostalgia and lover’s nuts.

Dwayne Hoover, six feet away, gazed out at the busy, sunny Interstate Highway. He knew where he was. There was a familiar moat between the parking lot of the Inn and the Interstate, a concrete trough which the engineers had built to contain Sugar Creek. Next came a familiar resilient steel barrier which prevented cars and trucks from tumbling into Sugar Creek. Next came the three familiar west-bound lanes, and then the familiar grassy median divider. After that came the three familiar east-bound lanes, and then another familiar steel barrier. After that came the familiar Will Fairchild Memorial Airport—and then the familiar farmlands beyond.

It was certainly flat out there—flat city, flat township, flat county, flat state. When Dwayne was a little boy, he had supposed that almost everybody lived in places that were treeless and flat. He imagined that oceans and mountains and forests were mainly sequestered in state and national parks. In the third grade, little Dwayne scrawled an essay which argued in favor of creating a national park at a bend in Sugar Creek, the only significant surface water within eight miles of Midland City.

Dwayne said the name of that familiar surface water to himself now, silently: “Sugar Creek."

Sugar Creek was only two inches deep and fifty yards wide at the bend, where little Dwayne thought the park should be. Now they had put the Mildred Barry Memorial Center for the Arts there instead. It was beautiful.

Dwayne fiddled with his lapel for a moment, felt a badge pinned there. He unpinned it, having no recollection of what it said. It was a boost for the Arts Festival, which would begin that evening. All over town people were wearing badges like Dwayne’s. Here is what the badges said:

Sugar Creek flooded now and then. Dwayne remembered about that. In a land so flat, flooding was a queerly pretty thing for water to do. Sugar Creek brimmed over silently, formed a vast mirror in which children might safely play.

The mirror showed the citizens the shape of the valley they lived in, demonstrated that they were hill people who inhabited slopes rising one inch for every mile that separated them from Sugar Creek.

Dwayne silently said the name of the water again: “Sugar Creek.”

Dwayne finished his breakfast, and he dared to suppose that he was no longer mentally diseased, that he had been cured by a simple change of residence, by a good night’s sleep.

Читать дальше