Dwayne awaited his turn humbly. He had forgotten that he was a co-owner of the Inn. As for staying at a place where black men stayed, Dwayne was philosophical. He experienced a sort of bittersweet happiness as he told himself, “Times change. Times change.”

The night clerk was new. He did not know Dwayne. He had Dwayne fill out a registration in full. Dwayne, for his part, apologized for not knowing what the number of his license plate was. He felt guilty about that, even though he knew he had done nothing he should feel guilty about.

He was elated when the clerk let him have a room key. He had passed the test. And he adored his room. It was so new and cool and clean. It was so neutral! It was the brother of thousands upon thousands of rooms in Holiday Inns all over the world.

Dwayne Hoover might be confused as to what his life was all about, or what he should do with it next. But this much he has done correctly: He had delivered himself to an irreproachable container for a human being.

It awaited anybody. It awaited Dwayne.

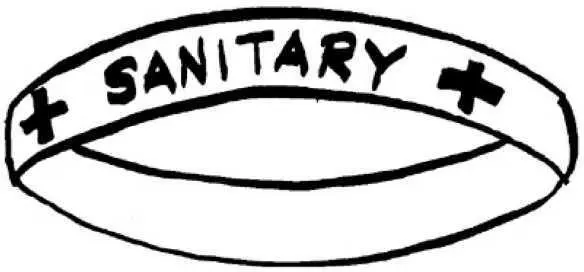

Around the toilet seat was a band of paper like this, which he would have to remove before he used the toilet:

This loop of paper guaranteed Dwayne that he need have no fear that corkscrew-shaped little animals would crawl up his asshole and eat up his wiring. That was one less worry for Dwayne.

There was a sign hanging on the inside doorknob, which Dwayne now hung on the outside doorknob. It looked like this:

Dwayne pulled open his floor-to-ceiling draperies for a moment. He saw the sign which announced the presence of the Inn to weary travelers on the Interstate. Here is what it looked like:

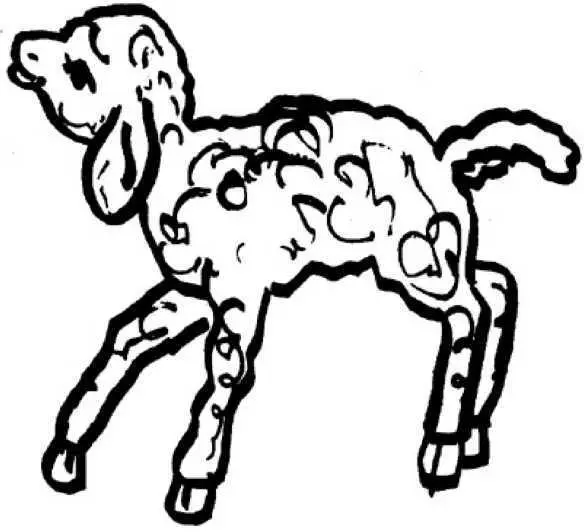

He closed his draperies. He adjusted the heating and ventilating system. He slept like a lamb.

A lamb was a young animal which was legendary for sleeping well on the planet Earth. It looked like this:

Kilgore Trout was released by the Police Department of the City of New York like a weightless thing-at two hours before dawn on the day after Veterans’ Day. He crossed the island of Manhattan from east to west in the company of Kleenex tissues and newspapers and soot.

He got a ride in a truck. It was hauling seventy-eight thousand pounds of Spanish olives. It picked him up at the mouth of the Lincoln Tunnel, which was named in honor of a man who had had the courage and imagination to make human slavery against the law in the United States of America. This was a recent innovation.

The slaves were simply turned loose without any property. They were easily recognizable. They were black. They were suddenly free to go exploring.

The driver, who was white, told Trout that he would have to lie on the floor of the cab until they reached open country, since it was against the law for him to pick up hitchhikers.

It was still dark when he told Trout he could sit up. They were crossing the poisoned marshes and meadows of New Jersey. The truck was a General Motors Astro-95 Diesel tractor, hooked up to a trailer forty feet long. It was so enormous that it made Trout feel that his head was about the size of a piece of bee-bee shot.

The driver said he used to be a hunter and a fisherman, long ago. It broke his heart when he imagined what the marshes and meadows had been like only a hundred years before. “And when you think of

the shit that most of these factories make—wash day products, catfood, pop—”

He had a point. The planet was being destroyed by manufacturing processes, and what was being manufactured was lousy, by and large.

Then Trout made a good point, too. “Well,” he said, “I used to be a conservationist. I used to weep and wail about people shooting bald eagles with automatic shotguns from helicopters and all that, but I gave it up. There’s a river in Cleveland which is so polluted that it catches fire about once a year. That used to make me sick, but I laugh about it now. When some tanker accidently dumps its load in the ocean, and kills millions of birds and billions of fish, I say, ‘More power to Standard Oil,’ or whoever it was that dumped it.” Trout raised his arms in celebration. “‘Up your ass with Mobil gas,’” he said.

The driver was upset by this. “You’re kidding,” he said.

“I realized,” said Trout, “that God wasn’t any conservationist, so for anybody else to be one was sacrilegious and a waste of time. You ever see one of His volcanoes or tornadoes or tidal waves? Anybody ever tell you about the Ice Ages he arranges for every half-million years? How about Dutch Elm disease? There’s a nice conservation measure for you. That’s God, not man. Just about the time we got our rivers cleaned up, he’d probably have the whole galaxy go up like a celluloid collar. That’s what the Star of Bethlehem was, you know.”

“What was the Star of Bethlehem?” said the driver.

“A whole galaxy going up like a celluloid collar,” said Trout.

The driver was impressed. “Come to think about it,” he said, “I don’t think there’s anything about conservation anywhere in the Bible.”

“Unless you want to count the story about the Flood,” said Trout.

They rode in silence for a while, and then the driver made another good point. He said he knew that his truck was turning the atmosphere into poison gas, and that the planet was being turned into pavement so his truck could go anywhere. “So I’m committing suicide,” he said.

“Don’t worry about it,” said Trout.

“My brother is even worse,” the driver went on. “He works in a factory that makes chemicals for killing plants and trees in Viet Nam.” Viet Nam was a country where America was trying to make people stop being communists by dropping things on them from airplanes. The chemicals he mentioned were intended to kill all the foliage, so it would be harder for communists to hide from airplanes.

“Don’t worry about it,” said Trout.

“In the long run, he’s committing suicide,” said the driver. “Seems like the only kind of job an American can get these days is committing suicide in some way.”

“Good point,” said Trout.

“I can’t tell if you’re serious or not,” said the driver.

“I won’t know myself until I find out whether life is serious or not,” said Trout. “It’s dangerous, I know, and it can hurt a lot. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s serious, too.”

After Trout became famous, of course, one of the biggest mysteries about him was whether he was kidding or not. He told one persistent questioner that he always crossed his fingers when he was kidding.

“And please note,” he went on, “that when I gave you that priceless piece of information, my fingers were crossed.”

And so on.

He was a pain in the neck in a lot of ways. The truck driver got sick of him after an hour or two. Trout used the silence to make up an anticonservation story he called “Gilgongo!”

“Gilgongo!” was about a planet which was unpleasant because there was too much creation going on.

The story began with a big party in honor of a man who had wiped out an entire species of darling little panda bears. He had devoted his life to this. Special plates were made for the party, and the guests got to take them home as souvenirs. There was a picture of a little bear on each one, and the date of the party. Underneath the picture was the word:

Читать дальше