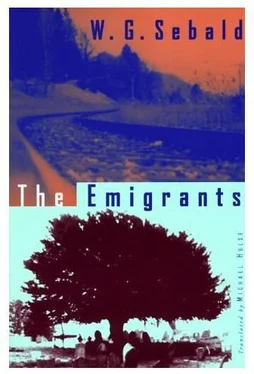

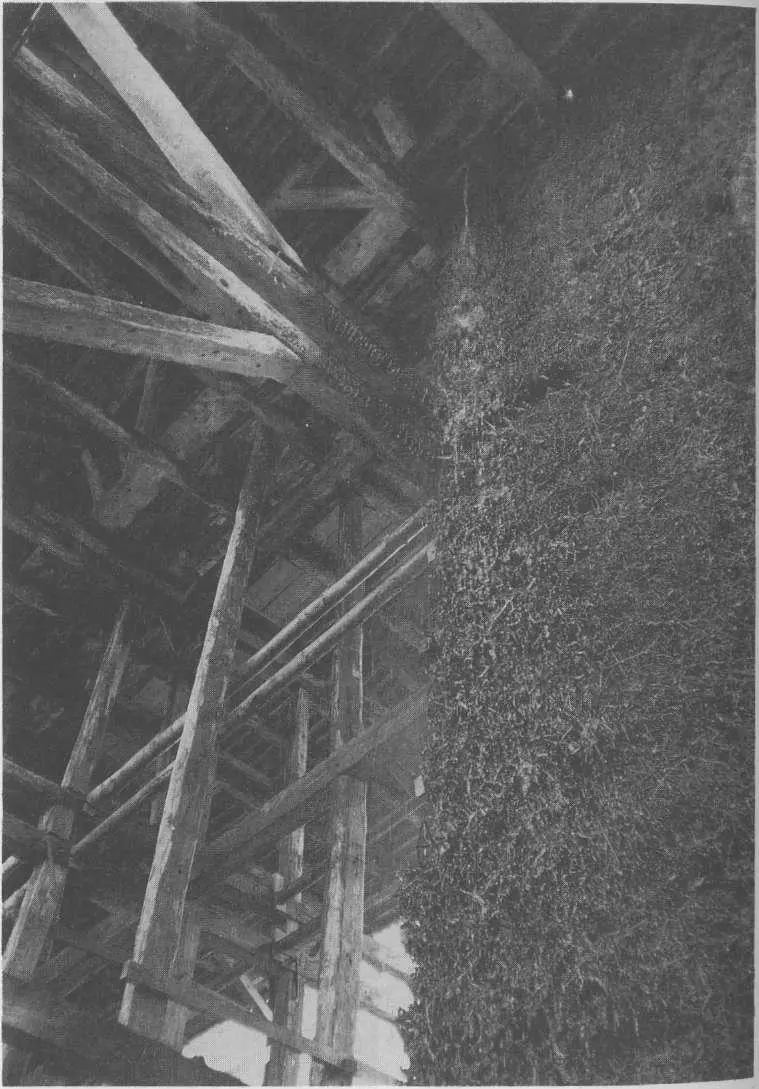

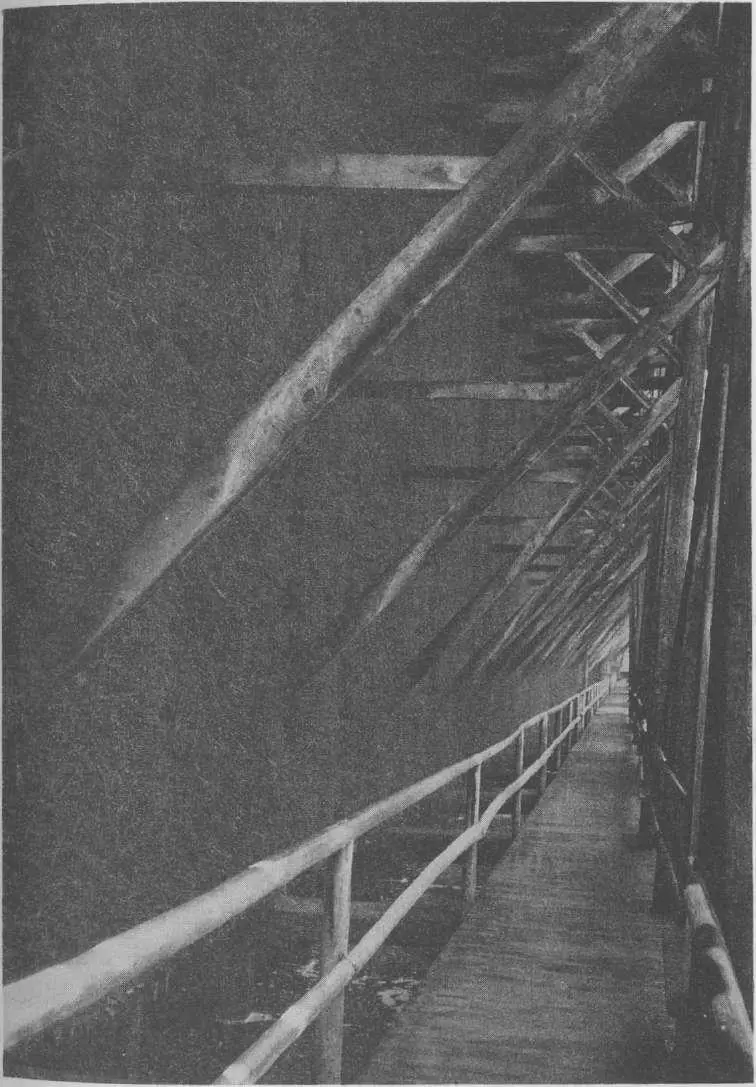

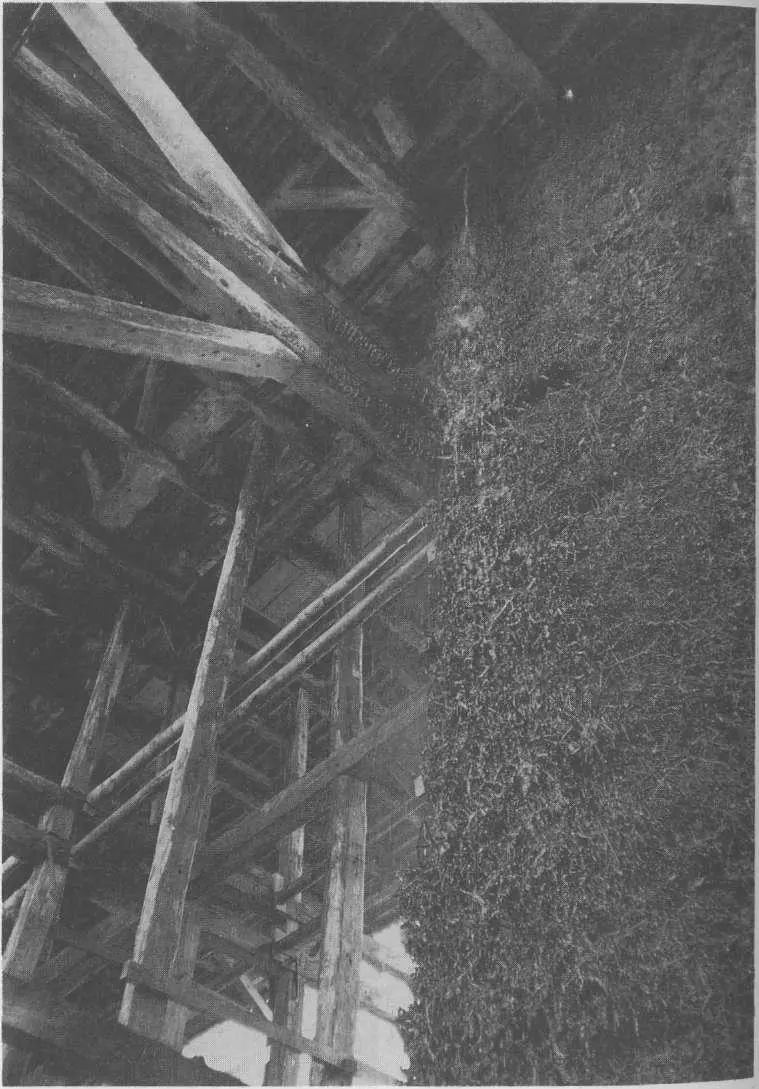

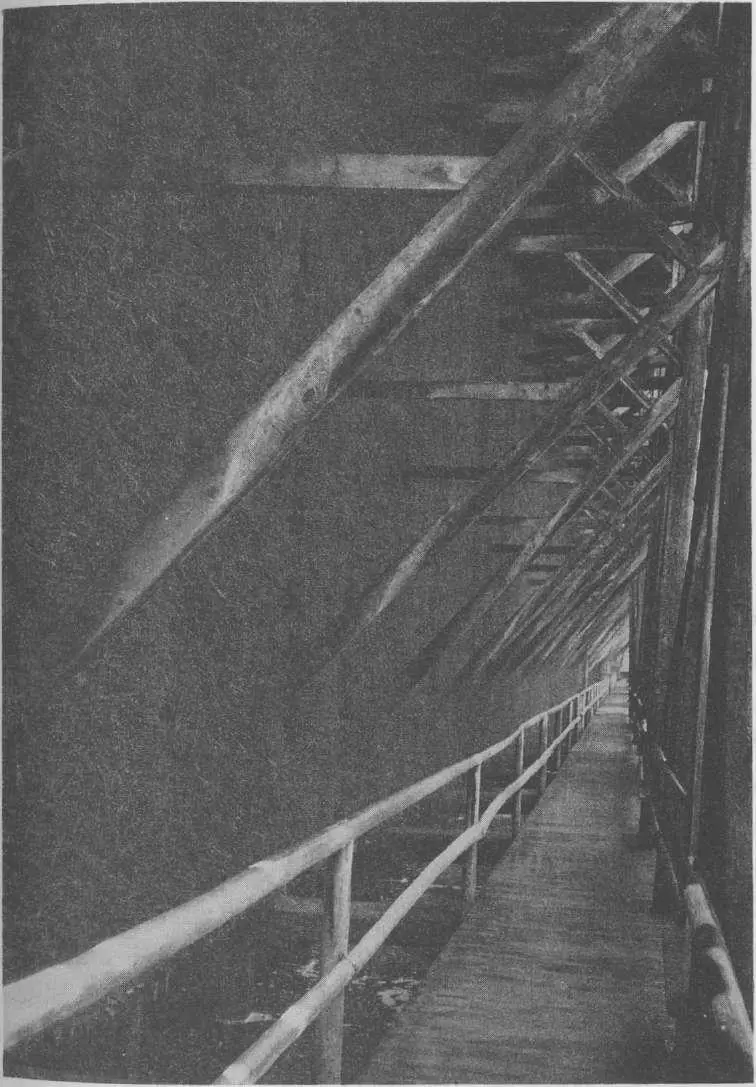

From there one could take a close look at the blackthorn twigs that were bunched in layers as high as the roof. Mineral water raised by a cast-iron pumping station was running down them, and collecting in a trough under the frame.

Completely taken aback both by the scale of the complex and by the steady mineral transformation wrought upon the twigs by the ceaseless flow of the water, I walked up and down the gallery for a long time, inhaling the salty air, which the

slightest breath of air loaded with myriad tiny droplets. At length I sat down on a bench in one of the balcony-like landings off the gallery, and all that afternoon immersed myself in the sight and sound of that theatre of water, and in ruminations about the long-term and (I believe) impenetrable process which, as the concentration of salts increases in the water, produces the very strangest of petrified or crystallized forms, imitating the growth patterns of Nature even as it is being dissolved.

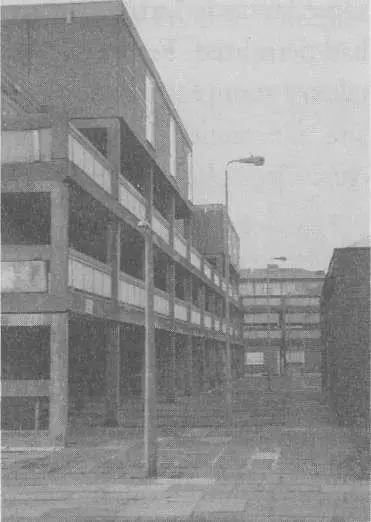

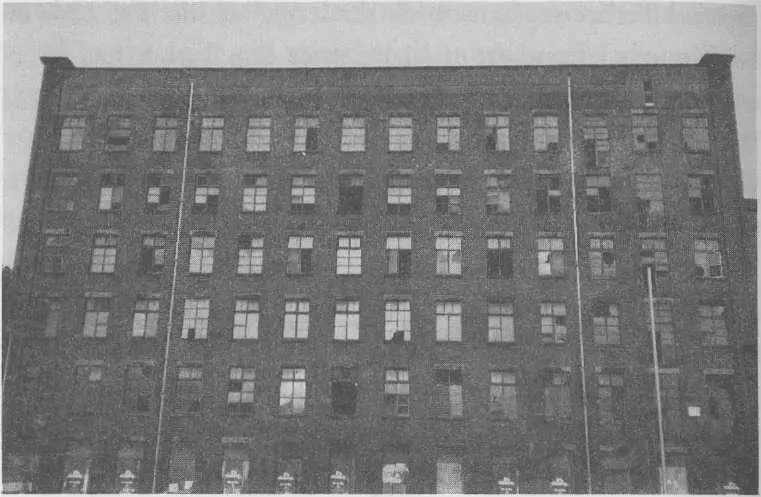

During the winter of 1990/91, in the little free time I had (in other words, mostly at the so-called weekend and at night), I was working on the account of Max Ferber given above. It was an arduous task. Often I could not get on for hours or days at a time, and not infrequently I unravelled what I had done, continuously tormented by scruples that were taking tighter hold and steadily paralysing me. These scruples concerned not only the subject of my narrative, which I felt I could not do justice to, no matter what approach I tried, but also the entire questionable business of writing. I had covered hundreds of pages with my scribble, in pencil and ballpoint. By far the greater part had been crossed out, discarded, or obliterated by additions. Even what I ultimately salvaged as a "final" version seemed to me a thing of shreds and patches, utterly botched. So I hesitated t0send Ferber my cut-down rendering of his life; and, as I hesitated, I heard from Manchester that Ferber had been taken to Withington Hospital with pulmonary emphysema. Withington Hospital was a one-time Victorian workhouse, where the homeless and unemployed had been subjected to a strict regime. Ferber was in a men's ward with well over twenty beds, where much muttering and groaning went on, and doubtless a good deal of dying. He clearly found it next to impossible to use his voice, and so responded to what I said only at lengthy intervals, in an attempt at speech that sounded like the rustle of dry leaves in the wind. Still, it was plain enough that he felt his condition was something to be ashamed of and had resolved to put it behind him as soon as possible, one way or another. He was ashen, and the weariness kept getting the better of him. I stayed with him for perhaps three quarters of an hour before taking my leave and walking the long way back through the south of the city, along the endless streets — Burton Road, Yew Tree Road, Claremont Road, Upper Lloyd Street, Lloyd Street North — and through the deserted Hulme estates, which had been rebuilt in the early Seventies and had now been left to fall down again. In Higher Cambridge Street I passed warehouses where the ventilators were still revolving in the broken windows.

I had to cross beneath urban motorways, over canal bridges and wasteland, till at last, in the already fading daylight, the facade of the Midland Hotel appeared before me, looking like some fantastic fortress. In recent years, ever since his income had permitted, Ferber had rented a suite there, and I too had taken a room for this one night. The Midland was built in the late nineteenth century, of chestnut-coloured bricks and chocolate-coloured glazed ceramic tiles which neither soot nor acid rain have been able to touch. The building runs to three basement levels, six floors above ground, and a total of no fewer than six hundred rooms, and was once famous throughout the land for its luxurious plumbing. Taking a shower there was like standing out in a monsoon. The brass and copper pipes, which were always highly polished, were so capacious that one of the bathtubs (three metres long and one metre wide) could be filled in just twelve seconds. Moreover, the Midland was renowned for its palm courtyard and, as various sources tell, for its hothouse atmosphere, which brought out both the guests and the staff in a sweat and generally conveyed the impression that here, in the heart of this northern city with its perpetual cold wet gusts, one was in fact on some tropical isle of the blessed, reserved for mill owners, where even the clouds in the sky were made of cotton, as it were. Today the Midland is on the brink of ruin. In the glass-roofed lobby, the reception rooms, the stairwells, the lifts and the corridors one rarely encounters either a hotel guest or one of the chambermaids or waiters who prowl about like sleepwalkers. The legendary steam heating, if it works at all, is erratic; fur flakes from out of the taps; the window panes are coated in thick grime marbled by rain; whole tracts of the building are closed off; and it is presumably only a matter of time before the Midland closes its doors and is sold off and transformed into a Holiday Inn.

When I entered my room on the fifth floor I suddenly felt as if I were in a hotel somewhere in Poland. The old-

fashioned interior put me curiously in mind of a faded wine-red velvet lining, the inside of a jewellery box or violin case. I kept my coat on and sat down on one of the plush armchairs in the corner bay window, watching darkness fall outside. The rain that had set in at dusk was pouring down into the gorges of the streets, lashed by the wind, and down below the black taxis and double-decker buses were moving across the shining tarmac, close behind or beside each other, like a herd of elephants. A constant roar rose from below to my place by the window, but there were also moments of complete silence from time to time. In one such interval (though it was utterly impossible) I thought I heard the orchestra tuning their instruments, amidst the usual scraping of chairs and clearing of throats, in the Free Trade Hall next door; and far off, far, far off in the distance, I also heard the little opera singer who used to perform at Liston's Music Hall in the Sixties, singing long extracts from Parsifal in German. Liston's Music Hall was in the city centre, not far from Piccadilly Gardens, above a so-called Wine Lodge where the prostitutes would take a rest and where they had Australian sherry on tap, in big barrels. Anyone who felt the urge could get up on the stage at that music hall and, with the swathes of smoke drifting, perform the piece of his choice to a very mixed and often heavily intoxicated audience, accompanied on the Wurlitzer by a lady who invariably wore pink tulle. As a rule the choice fell upon folk ballads and the sentimental hits that were currently in vogue. The old home town looks the same as I step down from the train , began the favourite of the winter season of 1966 to 1967. And there to greet me are my Mama and Papa. Twice a week, at a late hour when the heaving mass of people and voices verged on the infernal, the heroic tenor known as Siegfried, who cannot have been more than one metre fifty tall, would take the stage. He was in his late forties, wore a herringbone coat that reached almost to the floor and on his head a Homburg tilted back. He would sing O weh, des Höchsten Schmerzenstag or Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heut so schön or some other impressive arioso, not hesitating to act out stage directions such as "Parsifal is on the point of fainting" with the required theatricality. And now, sitting in the Midland's turret room above the abyss on the fifth floor, I heard him again for the first time since those days. The sound came from so far away that it was as if he were walking about behind the wing flats of an infinitely deep stage. On those flats, which in truth did not exist, I saw, one by one, pictures from an exhibition that I had seen in Frankfurt the year before. They were colour photographs, tinted with a greenish-blue or reddish-brown, of the Litzmannstadt ghetto that was established in 1940 in the Polish industrial centre of Lodz, once known as polski

Читать дальше